Meagen Benson searching the London Times for references to her ancestor, Mary Wade.

When Meagen Benson began researching her genealogy, all she knew was that she was a descendent of a female convict named Mary Wade, who had been transported from Great Britain to Australia. She knew nothing of her ancestor’s age, the crime she had been convicted of, or her legacy. The circumstances were identical for Helen Phillips — a distant relative of Rachel Hoddy — and Delia Dray — whose ancestor was Ann Marsh. To their surprise, Benson, Phillips, and Dray all found that with just a name and a date, it was possible for them to trace the astounding details of the lives of their forebears.

The Old Bailey and Newgate Prison

On January 14, 1789, eleven-year-old Mary Wade appeared before London’s Old Bailey court and was convicted of assaulting eight-year-old Mary Phillips and stealing her clothes. Sentencing her to death, the judge in Mary’s case stated that she and her accomplice’s crime was, “equivalent to holding a pistol to the breast of a grown person; therefore, I cannot state it to be any thing less than robbery; the consequence of that is, that they must answer it with their lives.”

Mary Wade was sent to Newgate Prison, one of London’s most notorious jails and a holding place for criminals awaiting “transportation” from Great Britain or facing death. Mary would have entered the prison through an underground tunnel that blocked out all natural light. Once inside, she would have been housed in one of a series of dark, wet, vermin-infested cells that were breeding grounds for diseases such as typhus. With over 750 men, women, and children contained within its walls — over twice its capacity — Newgate Prison was also severely overcrowded. Mary would have had the option of paying for a blanket or the privilege of sleeping on a wooden ramp at one end of the cell where she would have been slightly removed from the rats. But given that she was still a child, Mary likely slept on the floor huddled with the other poor female prisoners.

One of Mary’s fellow prisoners was prostitute Rachel Hoddy. Hoddy had stood trial at the Old Bailey on June 25, 1788 and had been sentenced to seven years transportation for stealing the clothes of her inebriated client, Nimrod Blampin. She, like Mary Wade and hundreds of other convicted criminals, had been sent to Newgate Prison in order either to wait for a ship to remove them from England or to take their final trip to the gallows. But neither woman could have guessed what fate had in store for her, or that her own journey would be retraced by her distant relatives over 200 years later.

Historical Records and Newspaper Archives

The ship manifest of the Lady Juliana.

What became of Mary Wade and how did she, along with Rachel Hoddy and Ann Marsh, end up on the Lady Juliana? For Meagen Benson and Helen Phillips, the descendents of Mary Wade and Rachel Hoddy, the first steps to unlocking the mysteries of their ancestors were to be found in the archives of the Old Bailey’s court proceedings — found online and at The Guildhall Library and The British Library. From over 100,000 records compiled from 1674 to 1834, the two women were able to locate trial summaries, court transcripts, and images of the original court records from Wade and Hoddy’s trials at the Old Bailey.

Once Benson and Phillips had uncovered how their ancestors became convicted criminals, their search led them on to other sources. In the archives of the London Times — one of the world’s most important historical records — Meagen Benson discovered why Mary Wade, who was originally sentenced to death, had instead been sent to the Sydney Cove colony. On March 11, 1789, “Mad” King George III was proclaimed cured of an unnamed madness — today, it is assumed that he suffered from porphyria, a degenerative mental disease. Five days later, in the spirit of celebration, all women on death row, including Mary Wade, had their sentences commuted to transportation. Wade was subsequently put aboard the Lady Juliana, the first convict ship to hold a cargo made up entirely of women and children.

Little was known about Ann Marsh and her crime other than that she was from Exeter and had been convicted of stealing a bushel of wheat. But Delia Dray was able to find the first important clue to Marsh’s story in a copy of the Lady Juliana’s manifest. The ship’s original manifest — kept at the State Library in Sydney, Australia — lists the names of all the female convicts aboard the ship, their ages, and their towns of origin. Dray found an entry for her ancestor in the manifest as “Marsh, Ann / Age: 21 / Town of Origin: Exeter.”

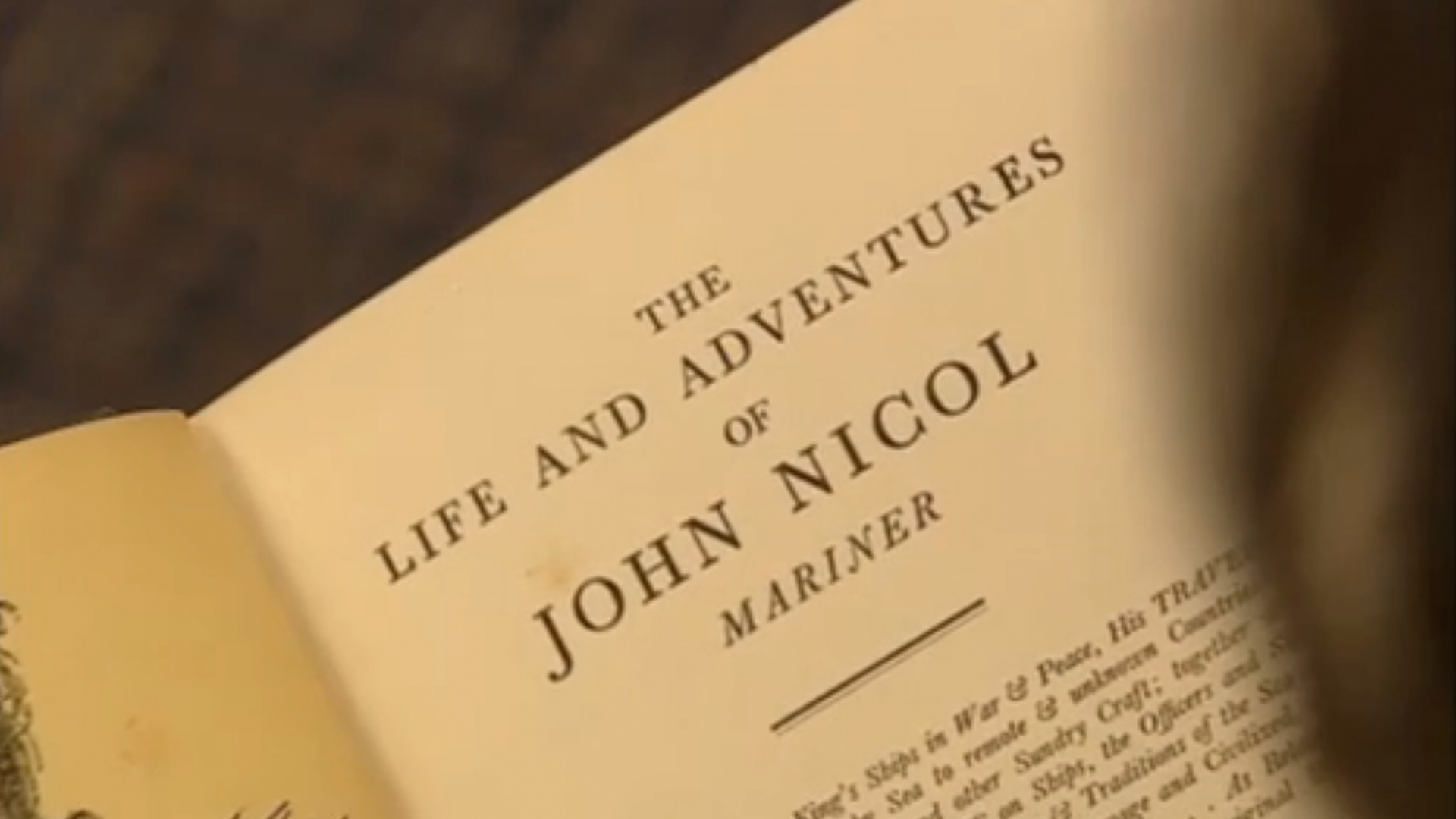

John Nicol’s Memoir

The Life and Adventures of John Nicol, Mariner was a valuable source of information about the journey of the Lady Juliana.

The Lady Juliana’s female convicts’ stories were never recorded, but ship steward John Nicol’s memoir contained one chapter dedicated to his time aboard the Lady Juliana. His book, The Life and Adventures of John Nicol, Mariner, recently reprinted in Australia, provides a respectful description of the ship’s journey and significant insights into its female passengers’ crimes and characters. Nicol described life onboard the ship and the ways in which the women were pressured to use sex to improve their situation and status. He details the difficult conditions the women were forced to endure during the long journey and the extreme seasickness that overtook the female passengers as they left England’s shores. But Nicol also notes that some luxuries were afforded to the women, even if they were primarily little more than efforts to safeguard the ship’s human cargo. The women were provided clothes, the services of a doctor, and guaranteed food and drink. Nicol also writes of how many sailors and officers took a “wife” on the journey and records the birth of seven babies aboard the Lady Juliana, including one to he and his own “wife,” Sarah Whitelam.

Using court records, the Lady Juliana’s manifest, and newspaper archives, the 21st-century women — Meagen Benson, Helen Phillips, and Delia Dray — were able to piece together the fates of their banished ancestors. Viewing a September 29, 1823 copy of the Hobart Town Gazette, Phillips learned that a license had been granted to Rachel Williams (formerly Hoddy) to sell liquor, wine, and beer in Hobart Town. To her surprise, Dray discovered that her ancestor Ann Marsh had founded the Parramatta River Boat Service, a line that still runs today. In the Sydney archives, Dray also found a copy of an unusual letter Marsh had written to the Governor of the Sydney Cove colony in 1811 requesting the services of a manservant to help operate her successful business. Benson was able to find out little more about Mary Wade until she uncovered her ancestor’s 1859 obituary in a local newspaper. The death notice stated that Wade had died at 87 years of age at her son’s residence. She is credited with being the matriarch of one of the largest families in the world, which grew to include five generations and over 300 descendents in her lifetime. She died highly esteemed and widely known throughout the colony.