In 1986, Dr. Susan Solomon traveled to Antarctica, where she led the research team that tied man-made chlorofluorocarbons to the hole in the ozone layer. “The station where I did my research on the ozone is actually located right at the spot where [Robert F.] Scott’s hut from his first expedition is located,” she says. “I was able to see the hut, walk to the hut, look around in the hut, and I just got intrigued by the whole question of what those guys did, why they did it.”

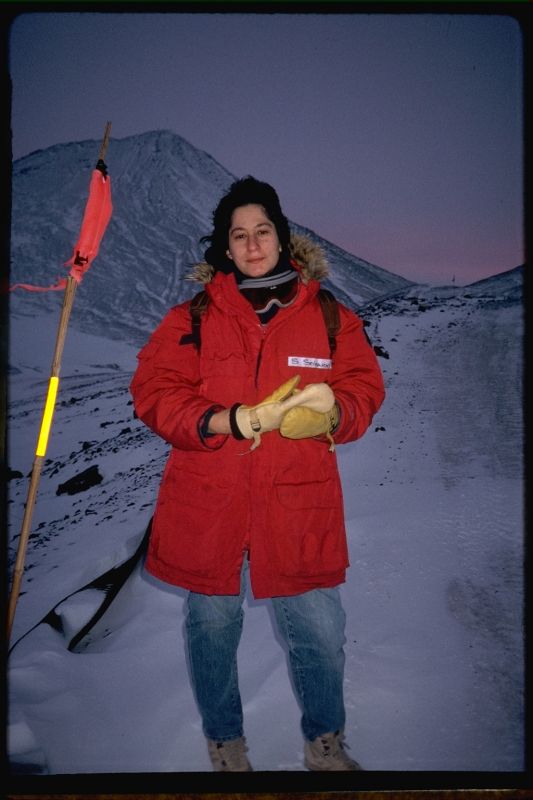

Dr. Susan Solomon, author of THE COLDEST MARCH

As she read about Scott’s trek to the South Pole, Solomon was intrigued by the idea of using modern science to explain the demise of his expedition. Her book, THE COLDEST MARCH, employs 20 years of meteorological data to support her contention that Scott’s team would have survived were it not for the extremely unusual weather they encountered. For the final month of their journey, these men were subjected to temperatures 30 to 40 degrees below zero. “It feels like crystal,” Solomon says of such weather. “Everything becomes stiff. Suddenly you’re clothing becomes stiff, because there’s enough moisture even in your jeans or whatever you’re wearing — those temperatures just freeze it up. And so your whole body, everything on you and everything about you, is turning to ice.”

Over the years, Scott has been portrayed as a bumbling captain whose poor leadership and inadequate preparation doomed his expedition and companions. “He certainly made some mistakes,” says Solomon. Leaky oil cans resulted in a shortage of oil during the last crucial weeks of Scott’s return from the Pole. Short on fuel, the team was unable to cook as much food or melt as much snow into water that would allay their dehydration. “Not resoldering the oil cans was definitely a mistake. I don’t think that it alone would have led to his death. They certainly would have had enough food if they had been going the normal rate of speed.”

Instead, the unusual temperatures rendered the ground surface — over which Scott and his companions had to drag their sledges — a sand-like texture. It was simply impossible to keep up the pace. “Suddenly they were only making five miles a day in an area where they had to be making fifteen in order to get to the food. If they had been experiencing the kind of conditions that the other parties experienced and which they broadly expected, then food wouldn’t have been a problem. Similarly, having less oil becomes a problem because you’re going three times slower. The oil would have been a problem, but it certainly wouldn’t have led to their deaths. Everything becomes a huge problem when you’re only making a third of the speed you need to make and your supplies have been laid out at a certain pace. So that was really what did it.”

Solomon feels that, essentially, it came down to luck. “As Scott said, ‘we took risks, we know we took them.’ It isn’t the case that he didn’t allow for the idea that the weather could be unusual. I mean, everyone knows that you can sometimes hit unusual weather. So he took a chance and it turns out nineteen times out of twenty he probably would have been fine, but he hit the unlucky twentieth. Having had that happen, there was really nothing they could do.”

Roald Amundsen, the Norwegian explorer who beat Scott to the Pole, counted on luck as well. “We now know the place where Amundsen put his camp breaks out and floats out to sea about one year in every fifteen, so he hit the lucky fourteen out of fifteen where that doesn’t happen,” Solomon says. “I think what people don’t realize when they read these tales of high adventure and exploration is that luck is always a key part of it. We tend too often to say that when somebody succeeds it’s because of their talent and their brilliance alone, and if somebody fails it must be because they’re terribly dumb and stupid. I think that’s a little bit natural, because we admire these men so much … the ones who succeeded must have been really great. And maybe that’s not true; maybe they just got lucky. And the ones who didn’t succeed, maybe they weren’t the donkeys that we make them into. They just had a bit of bad luck.”

According to Solomon, “the most interesting part of the whole story is actually the human side of the story. It’s the fact that these men had such remarkable dedication to their shared mission, and to one another. I find it truly a moving experience to even learn about what those guys did and the reasons why they did it and the ways in which they did it. They deserve our admiration on so many levels. Not just the physical courage that they had, but the tremendous human characteristics of these men. If the book [THE COLDEST MARCH] does anything, I think what it does is to tell you about them as people as well as telling you about the natural world that they faced — showing you how the ferocious nature of Antarctic weather is something so powerful that sometimes even the strongest men, even men like these guys, just couldn’t withstand it.”