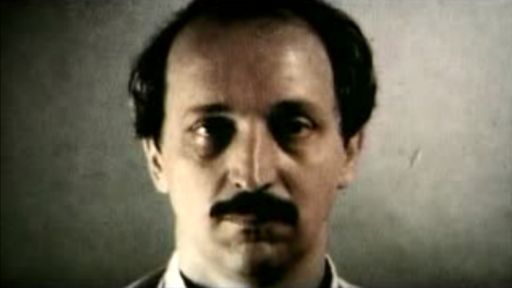

Georgi Ivanov Markov was born on March 1, 1929 in Sofia, Bulgaria, which came under the control of the Bulgarian Communist Party in 1944. Although his father was a “class enemy” of the party, Markov published his first novel at the age of 32 to stellar reviews, and he eventually became an acclaimed novelist and playwright. His life among the privileged elite in Bulgarian society — including among communist party members — ended in 1969, when he defected to Italy after learning that his last play had angered the government and put him at risk. By 1971, Markov had immigrated to England, where he received political asylum. After his defection, he was accused by Bulgarian authorities of being a traitor, and tried and convicted in absentia.

Bulgarian author and dissident Georgi Ivanov Markov.

Markov became a broadcast journalist and commentator for the BBC, reporting on news and cultural affairs behind the Iron Curtain. In June 1975, he began contributing programs to Radio Free Europe, a station funded and supported by the CIA. His weekly shows were sharply critical of Bulgarian bureaucrats and communist party officials, most notably, party leader Todor Zhivkov. Over the next three years, Markov’s programs increasingly inspired dissidents within Bulgaria. Zhivkov and the Bulgarian secret police reportedly enlisted the help of the Soviet KGB to silence Markov — for good.

In early 1978, Markov began receiving telephone death threats. In the last call, in August 1978, a man told Markov that he would die of natural causes, killed by a poison the West could not detect or treat.

Reenactment showing Georgi Ivanov Markov standing at the bus stop where he was pricked with a specially-modified umbrella containing a pellet with the poison ricin.

Two weeks later on September 7, Markov was at a parking lot on the south side of the Waterloo Bridge in London, where he always caught a bus across the bridge to go to work at BBC Headquarters. At the bus stop, he felt a sharp stinging sensation in the back of his right thigh. When he turned around, he saw a man bending over to pick up a dropped umbrella. The man, who was facing away from Markov, said “I’m sorry” in a foreign accent, then hailed a cab and left.

Markov was in pain, but went to work and told his colleagues what had happened. He noticed a pimple-like swelling on his thigh, and some blood on his jeans. That evening, he developed a high fever; by the next day, he was having trouble speaking. He was admitted to the hospital, where doctors initially began treating him for septicemia, or blood poisoning. Over the next several days, his body began to fail: his blood pressure collapsed, he began vomiting blood, his kidneys began to die. On the morning of September 11, 1978, the conduction system of his heart — the ‘pacemaker’ that regulates the beating of the heart’s atria and ventricles — failed. His heart stopped. Georgi Markov was dead.