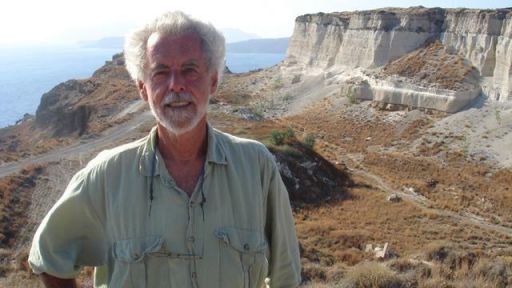

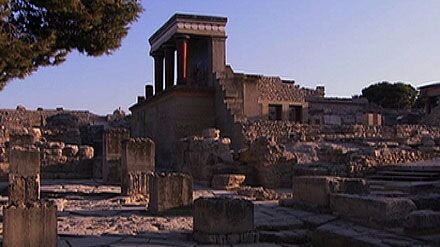

Sandy McGillivray, an archaeologist studying the Minoan ruins of Palaikastro on the eastern shore of Crete, had never seen anything like it. While strolling along the beach, McGillivray noticed bits of ancient pottery, building debris, and volcanic ash mixed into the sediment layers of an eroding cliff side.

How the debris ended up there had him stumped.

He decided to call Hendrik Bruins, a soil scientist from Ben Gurion University in Israel who specializes in dating and identifying unusual layers of sediment. Bruins examined the layers, but their composition confused him too.

“This, from a sedimentary point of view, is impossible to get by an earthquake and it’s impossible to get by natural archaeological stratification,” Bruins concluded.

As Bruins studied the sediment deposits under a microscope, he discovered something else mixed in with the ancient debris and ash: foraminifera – tiny marine organisms – along with coralline algae. What were marine organisms doing in a sediment layer a few meters above sea level? Bruins could think of only one natural force capable of such a feat.

A sudden, devastating, and powerful wave.

Below, investigate for yourself by comparing the three major classifications of sedimentary rock with the bizarre deposit Sandy McGillivray discovered in the cliffs at Palaikastro.

Sedimentary rocks fall into three categories:

Clastic rocks

Clastic sediment layers, like sandstone (pictured) and shale, form when rock fragments are broken down by weathering – a decomposition process that occurs when rocks come into direct contact with heat, water, ice, pressure, and natural chemicals – and are then transported and deposited elsewhere.

Chemical rocks

Chemical rocks, like halite (rock salt) and gypsum, form when minerals that exist in a solution are extracted after the solution evaporates. For instance, when large bodies of saltwater dry up, they leave behind halite (pictured).

Biochemical rocks

Biochemical rocks, like coal and oil shale (pictured), form when the remains of dead organisms such as coral and mollusks merge with existing sediment.

Often, biochemical rocks contain the same foraminifera that Hendrik Bruins found in the Palaikastro layer. However, it would be impossible for marine organisms and ancient pottery debris to exist in the same rock layer unless something forced them together, which is why Bruins suspected a fierce wave struck Palaikastro.

Now compare the three major types of sediment to the Palaikastro layer:

Palaikastro deposit

Mixed into the sediment, you can clearly see floor plaster, wall plaster, and fragments of typical Minoan pottery. The existence of the Minoan fragments in conjunction with the marine organisms suggests that a massive amount of ocean water swept ashore, destroyed Minoan structures, and then swept the debris back toward the sea when the water finally receded.

Find out how Bruins and McGillivray prove a tsunami destroyed ancient Minoan society in the full episode of “Sinking Atlantis.”