TRANSCRIPT

December 23rd 1888.

The city of Arles, South of France.

While the townsfolk prepare for Christmas, one man is about to commit one of the most infamous and bloody acts in the history of art.

His name: Vincent van Gogh…

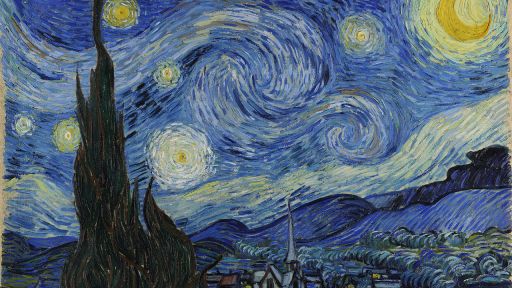

…the genius who created some of the most iconic and valuable paintings in the world.

But on that night, driven to madness, he cuts off his ear and delivers it to a girl in a brothel.

His paintings would turn him into one of the most renowned artists on the planet… but his madness would make him the center of a mystery.

For more than a century, no one has agreed on exactly what happened that fateful night. Did Vincent really cut off his ear? Why did he do it? Who was the mysterious prostitute?

Now, one woman, Bernadette Murphy, is on a mission to find out the truth.

Uncovering lies…

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator There is something seriously wrong here

…hunting for every scrap of evidence…

Bernadette Murphy You have to look in places no-one else has looked

…on an epic journey, across countries and continents, to find the truth about Vincent van Gogh.

Bernadette Murphy O mon dieu, je l’ai trouvé. Oh my god, I’ve found it.

TITLE SHOT

In 1888, the sun-drenched region of Provence in the south of France witnessed the arrival of an outsider: a strange Dutchman, aspiring artist Vincent van Gogh.

During his 15-month stay in the city of Arles, Vincent would paint more than two hundred paintings that captured the people and places he encountered.

But during his time here, he would also suffer a cataclysmic breakdown, culminating in an act of bloody self-mutilation.

What led to the tragic downfall of this tortured genius? Did he cut off his whole ear? Or, as some believe, just a small piece of it?

Bernadette Murphy moved here from England over 30 years ago, and the Vincent van Gogh mystery has become a passion that changed her life.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

Every time I would ever bring friends or family to Arles, the first thing they would always know about Vincent van Gogh was - he was the man who cut off his ear. And yet when you look in art books they say that he only cut off the lobe.

In fact, it seemed no one could agree on what exactly happened.

On the night of December 23rd, while most of Arles was celebrating Christmas…

…a horrific incident occurred in a northern district of the city.

Vincent took a razor to his ear and sliced it off. He then wrapped the bloody ear in a cloth, left his house on Place Lamartine and went to the Rue du Bout d’Arles in the heart of the red light district.

Knocking on the door of a brothel, Vincent then asked for a girl, and handed her the bloody package.

She fainted at the sight of it, while Vincent disappeared into the night and then returned home, to be found slumped in a sea of blood the next morning.

But while all the newspaper reports agreed on the big picture: that a man had cut off his ear before turning up at a brothel and handing it to a prostitute, they disagreed on the details.

Some reports even labelled Vincent - a Dutch man - as Polish.

Bernadette was intrigued.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

When I started to look into the story, I kept finding holes in the official version – things that didn’t make sense. So soon I realized there was only one solution and that was to begin at the beginning and look at the story as a detective would.

With so many inconsistencies in the story, Bernadette was determined to find out what, if any of it, was true.

First, she headed to the world’s leading center for Van Gogh research– the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

The museum has the largest Van Gogh collection in the world with more than 200 paintings, 400 drawings and 700 letters by the artist.

Many of the works are now globally iconic, and the museum pulls in an incredible 1.9 million visitors each year.

With such intense fascination about Vincent’s life and work, the museum gets thousands of Van Gogh inquiries each year from independent researchers like Bernadette.

Louis van Tilborgh, Senior Researcher, Van Gogh Museum

People are always obsessive about the artist in the sense that they tend to think that they’ve got a personal relationship with him, and it has something to do with the fact that he makes very accessible art, memorable kind of pictures that he makes, very easy to remember. And I have to tell you that there are many amateur historians who are interested in questions of Van Gogh and try to solve them by themselves and Bernadette was such a person.

Convinced by her enthusiasm, the museum has given Bernadette special access to a key piece of evidence.

Bernadette Murphy Great… great.

These research notes include a witness statement from Van Gogh’s friend and fellow painter, Paul Signac.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

Paul Signac, he had actually been in Arles and had gone to see Vincent after he cut off his ear. So it says ‘I saw him the last time in Arles in the spring of 1889. He was already at the hospital at the time. A few days earlier, he had cut off the lobe of the ear and not the ear, in the circumstances that you know.

I mean what he’s saying there, he cut the lobe of the ear and not the whole ear. It really just says that Vincent wasn’t as crazy as all that.

Well I’m starting to think that this might well be a minor incident and that the whole story has become exaggerated over time. That a man would cut the lobe of an ear, especially as - There's something wrong here though because the local newspaper said, he cut off his ear.

For many, this story about the lobe has become gospel, but even the museum experts admit it is confusing.

Teio Meedendorp, Senior Researcher, Van Gogh Museum

Who to believe? That’s always been the question, who to believe? Signac said, for instance, when he saw him there, that Vincent was still wearing the beret or the fur hat that he had at the time, and his bandages, so he couldn’t have seen the ear.

The more reliable, is some of these people who were close to him, who saw him, who knew him for a couple of times and who saw him, and they said it was half the ear. So that has always been our point of view.

Was this a minor incident as the art historians believe or the tipping point for a man who just 18 months later would commit suicide?

Throughout his life, Vincent suffered with mental illness.

Born March 30th, 1853 in Holland, he was the eldest son of a Protestant minister.

Vincent was expected to conform to a strict, religious upbringing.

At the age of 16, he went to work at his uncle’s art dealership. But things soon started to go wrong.

Steven Naifeh, Biographer

You have a person who was alternately unbelievably depressive or unbelievably manic. But he was also terribly argumentative, so that left him literally in a life of almost no friendship, and with a family that would - despaired over him.

Struggling to fit in, Vincent was forced to leave his job and withdrew from society at age 23.

Louis van Tilborgh,

Here we’ve got this man who has failed, convinced of the fact that he can do something but not knowing what to do. Then his brother says. “Why don’t you become an artist?”

Theo, Vincent’s younger brother, also worked in the family’s art dealing firm, but he succeeded where Vincent failed.

Steven Naifeh, Biographer

Without Theo there would have been no Vincent. If Theo had not kept him alive, kept him relatively coherent and paid for his existence and recommended that he start painting in the first place, there would be no Vincent van Gogh. We owe much of this to Theo’s love and fraternity and patronage.

In 1880, at the age of 27, Vincent threw himself into his art.

But his early works in Holland were dark and somber – very different from his later paintings.

In 1886, he decided to move in with Theo in Paris.

There, in the bright lights of the big city, Vincent developed a lighter, more colorful style.

However, he again began to feel like an outsider which led to his momentous decision to move south.

On February 20th 1888, he arrived in Arles.

Had Vincent finally found his utopia? Or had he brought his emotional baggage with him?

On her quest to find out the truth about Vincent’s ear, Bernadette Murphy wants to know how he coped with his relocation.

More than anyone else who has researched Van Gogh, she understands how difficult life can be as a newcomer to Arles.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

I came to Provence more than 30 years ago now. I am and always will be a foreigner in a foreign country - an outsider if you will.

But in Provence there’s another notion of an outsider that is much more subtle if you don’t live here.

You can be French but you can be what is considered an “estranger”. It means somebody who’s not from your network, your immediate environment, and therefore there’s a subtext to this that perhaps they’re not really trustworthy.

Vincent, when he came to Provence, was an “estranger”.

When Vincent arrived in 1888, Arles was just a small provincial town, its architecture dominated by the legacy of the ancient Romans who’d settled there more than two thousand years before.

The town was rooted in a culture that had remained unchanged for centuries.

Its people sounded different, speaking in their own dialect.

They looked different, dressing in their own unique Arlesien costume, and they acted differently, practicing traditions you’d be more likely to witness in Spain than anywhere else in France.

But despite being a stranger in a foreign land, Vincent got lucky with his chosen neighborhood.

The Place Lamartine was a relatively new part of town. Having developed after the arrival of the railway in 1840, this neighborhood was used to the comings and goings of strangers.

Vincent soon became friends with the owners of the Café de la Gare, the station café.

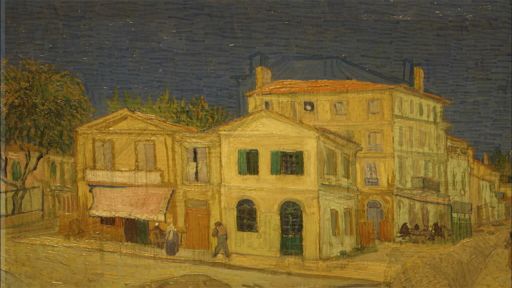

And it was these café owners, Monsieur and Madame Ginoux, who found Vincent the home where his triumphs and tragedies would play out. Unfortunately, the building was destroyed in World War Two.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

He spoke to the Ginoux family, and they said ‘you can stay here for a few months until the house is ready’. And so Vincent took over a house that was a bit run down. The plan was that it was going to be restored and Vincent chose the color of green for the shutters and the butter yellow of the walls.

For Vincent, the yellow house was not just a home, but a base for his far greater ambitions as an artist which were, like everything else, financed by Theo, his brother.

Teio Meedendorp Vincent had had some extra money from Theo, and he could buy chairs and tables, he could buy beds. He is making a decoration for this yellow house, so it is a true artist’s home. Also for non-artists to visit, so they can tell that this is a special place, this is where art is, and where you can look at art.

The yellow house was at the heart of Vincent’s mission to create a modern artistic brotherhood in the south of France. Vincent seemed happier than he had ever been.

He began to paint obsessively.

Steven Naifeh, What’s astonishing about Arles is that he could in a single day make a great painting that is so intense and so iconic.

Inspired by the beauty of the surrounding landscape, Van Gogh created more than a hundred paintings.

Were Vincent’s artistic achievements in the summer of 1888 the sign of a genius who’d found his path?

Or was this feverish activity actually evidence of his mental decline?

Louis van Tilborgh So you’ve got an artist who thinks that he will improve his art by working quickly, and so he has to get into the mood to do it as quickly as possible.

In a letter to Theo, Vincent wrote … ’I am working as one possessed.’

Louis van Tilborgh People who saw him at the time, probably see him as a kind of maniac.

It’s said that the locals nicknamed him ‘Le Fou Roux’ – the red-headed madman. But was he really a maniac capable of cutting off his own ear?

Local legend before the time of the incident suggests Vincent was feared as a danger not only to himself but the whole population.

And the townspeople even tried to banish him from Arles.

But is the story true?

Bernadette tracked down town records in the city archive in the Hotel Dieu which ironically was once a hospital and is where Vincent was treated after the ear-cutting incident.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

The document is written to the mayor and it says, “We the people of Arles, the people who live around the Place Lamartine, would like to draw your attention that Mr. Vincent is suffering from mental disturbance, he drinks too much, and we think it would be good if he was sent back to his family or he was placed in a mental institution”.

Vincent thought that there were 80 signatures, he says in his letters “80 people signed a petition to get me out of the city.” And later this was exaggerated: a hundred people signed it. There are actually only 30 people. If you count them there are 30 signatures.

Bernadette analyzed every signature to determine the identities of Vincent’s accusers, and her research revealed a disturbing pattern.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

It took quite a bit of time but slowly I worked out who everybody was. So the first name is Damaz Crèvoulin, épicier, and that’s Vincent’s next door neighbour. The writing seems to be the same as the signature so we think he actually wrote the petition out. And the other person who’s very important in this is this very pale one there which is Mr. Soulé who was Vincent’s house agent, he organized the rentals. And all of these people were cronies of these two men.

Vincent wrote that these men had tried to replace him with another tenant.

When this failed, Bernadette believes they created a smear campaign to evict him from his home.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

One very famous art historian called it ‘a conspiracy of hyenas’. Really a violent image of the whole town being up in arms against this poor sick man, and him being chased out by the local populace, you know. It’s nothing of the sort!

In fact, it was organized by two men who got their friends to sign it. They had a vested interest in getting Vincent out of the yellow house.

In fact, Vincent made many close friends: from soldiers stationed in Arles, to the café owners. Even the local postman, Joseph Roulin and his family.

Rather than making a public nuisance of himself, or being in constant battle with angry neighbors, Van Gogh spent the summer of 1888 engrossed in art.

The walls of the yellow house were soon covered with paintings inspired by his Arles experience.

They included a subject that would spawn some of the most iconic paintings the world has ever seen.

Teio Meedendorp, Senior Researcher, Van Gogh Museum

Vincent made a series of flower still lives in Arles in the summer of ’88 when they were blooming. So what you see here is a whole arrangement of different shades of yellow, going from a sulphurous yellow, greenish yellow, to darker ochre colors and every hue in between.

This was something completely new.

Vincent wasn’t just trying to push the boundaries of modern art; he was trying to create art that would attract other artists to join him, to realize his dream of an artist’s colony in the South.

With the sunflowers, he had a very specific painter in mind: Paul Gauguin.

Unlike Vincent, Gauguin had already become something of a celebrity in the modern art world. Vincent’s brother Theo had put on a small exhibition of his work.

If Vincent could persuade Gauguin to come to Arles, it would be the start of his dreamed-of artistic brotherhood.

Teio Meedendor He knew that Gauguin was interested in sunflowers and he actually wrote to him that he decorated his room with the series of sunflowers.

Whether Gauguin was lured by the sunflowers, by Vincent’s promise that Arles was full of beautiful women, or by Theo paying for his move, on October 23rd, 1888, Gauguin took up residence at the Yellow House.

Louis van Tilborgh,

Gauguin was a man of the world, Van Gogh wasn’t. Totally the opposite. Gauguin might have been a bit arrogant, Van Gogh might have been aggressive, there were differences in character, but nevertheless in principle if you look at the total, I think they liked each other.

Vincent now believed he had a soul mate and his dream of an artistic commune was taking shape. Was it possible that just two months later, he would have been capable of cutting off his ear?

Vincent never fully explained his self-inflicted violence, but he did paint himself immediately after. Bernadette believes these portraits provide fascinating clues.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

In “The Bandaged Ear and Pipe” you can see a bandage that goes under his neck and down into his body.

Underneath the bandage is a large piece of wadding, and the wadding is thick. I talked to different doctors about his injury, and I explained the scenarios that it could have been a lobe, part of the lower part of the ear, the whole ear or not the whole ear.

And a doctor remarked, “I believe that seriously you would need extra wadding”, which would imply that the injury had been bigger than just the lobe. Now this made me think this lobe story is beginning to look less and less likely.

Bernadette is not the only one who believes Vincent’s paintings hold important clues to the ear mystery.

Holland’s Kröller-Müller Museum owns another intriguing Van Gogh painting. Recent analysis offers insight into Vincent’s mental state at the time of the incident.

Marieke Jooren,

Van Gogh painted this still life shortly after he returned from the hospital. And you could actually see it as a self-portrait, about his life in Arles, about his state of mind.

The painting shows his increasing dependency on both alcohol and tobacco in the run-up to the night in question.

The candle represented Gauguin’s importance as a shining light in Vincent's life, while perhaps he used the medical booklet to treat his own injury.

Marieke Jooren But perhaps the most interesting thing in this painting is the letter that we see over here.

Overlooked for more than a century, this letter is a vital clue to Vincent’s state of mind on the night he took a razor to his ear.

Marieke Jooren, Kröller-Müller Museum

And in 2009 the researchers found out by who the letter was written. Very important evidence are the stamps that you see. Over here you see the number 67 which indicates the number of the post office where it was stamped. And this is near the apartment of Theo his brother.

Then there’s the mark saying “Jour de l’ans” which was used by the post office in very busy time around Christmas and New Year. Then of course they had a look at the handwriting, and with all these clues they couldn’t conclude anything else than it has to be a letter by Theo and it has to be the letter that arrived in Arles on 23rd December.

Arriving on the very day of the incident, scholars believe it contained devastating news.

Marieke Jooren, Kröller-Müller Museum This is probably the letter in which Theo announces his engagement to Jo Bonger, and the theory is that it caused Vincent’s mental breakdown because he was so afraid of losing his brother’s support, and Vincent not being the most important person on earth any more.

Theo had supported his brother financially throughout his career, and now Vincent’s means of survival might disappear as his brother took on the responsibilities of marriage and family life.

Could Theo’s news have driven Vincent to despair and self-mutilation? It came at a moment when he was already at his most vulnerable.

His relationship with Gauguin was falling apart. They were complete opposites.

Although friends at first, they had very different personalities. Unlike Vincent, Gauguin was confident, charismatic, commercially successful and a serial womanizer.

Stephen Naifeh, Biographer

Gauguin was sort of a jerk. He arrives in Arles, this ladies man who has a pretty strong ego and he finds himself in this house with this very difficult person with almost no self-esteem and it’s a terrible situation. He’s only there because Theo is paying him. Almost within days of arrival he’s sending his friends back in Paris letters saying, “I gotta get out of here. I can’t possibly take this any longer.”

The Van Gogh Museum has a collection of the artist’s letters revealing the falling-out between the two.

Nienke Bakker, Curator, Van Gogh Museum At some point Gauguin writes to Theo that he will have to leave because it’s not going well between him and Vincent.

They don’t agree on art, on the artists that they admire and they have a lot of discussions and Vincent is saying that these discussions are excessively electric. He uses the word “electric”. “And afterwards our heads are like run down batteries”, so I think that’s expressing very well the state that he’s in just before the incident.

On the very day that Vincent received news of Theo’s engagement, Gauguin announced he’d had enough and was leaving.

Vincent had lost his brother, his companion and his dreams for the yellow house. That night, he had the breakdown.

As an eyewitness to the events leading up to Vincent’s terrible attack, Paul Gauguin gives us a fascinating insight. His notebook is full of sketches and notes about the night in question.

Bernadette Murphy This is a whole list of words. They just seem random at first. They say inca, snake, fly on a dog, black lion.

Experts believe Van Gogh used these words bitterly to insult Gauguin when he announced he was leaving.

Inca – Gauguin was born in Peru. Snake, fly on the dog, black lion.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

And then it says, “Save your honour, money on the table”. I could imagine Gauguin wanting to leave Arles and saying, “I need some money, I’ve got to go”, and Vincent saying, “OK, here it is”. So I think this strange series of words is in fact a little sort of memo to himself of what was happening in the yellow house the day of the drama.

Other jottings in Gauguin’s notebook, give even more tantalizing clues as to Vincent’s state of mind that night.

While the word ‘ictus’ is a historical term for a psychotic fit, it is also the name of a symbol for Christianity.

And it wasn’t the only religious association with mania recorded in Gauguin’s notebook.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

But that wasn’t really what was intriguing. It was this part it said “Sain d’esprit, Saint Esprit”, and in Gauguin’s autobiography he puts this. He says that Vincent wrote this on the wall of the yellow house. I am “sain d’esprit” means “I’m healthy”, and he plays with it – I am the Holy Ghost, so he’s obviously having mystic delusions.

Vincent’s religious upbringing had instilled a protestant work ethic that drove him to paint obsessively and had often been at the heart of his anguish when things didn’t go according to plan.

Various theories exist about why Vincent chose his ear to butcher.

He admired a painting by Giotto of the arrest of Jesus, when Jesus is kissed by the traitorous Judas Iscariot.

But it also depicts St. Peter cutting the ear off one of the arresting soldiers. Is that what Vincent was imagining?

Others believe Van Gogh was mimicking a victorious bullfighter.

Having defeated the beast, the fighter cuts off the bull's ear and gives it as a bloody gift to a girl in the crowd.

With Vincent facing these numerous setbacks, we can only imagine what was going through his mind.

Thoughts of losing his brother and Gauguin’s betrayal…

Memories of his triumphs and tragedies, his time in Arles, his past sexual failures, the paintings he’d painted, and his religious obsessions.

Now he was alone with a razor in his hand.

But did he cut off his whole ear?

Despite her exhaustive research, Bernadette has never been able to find any accounts from the man who actually treated Vincent: Dr. Felix Rey.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator Dr. Rey spoke to many people but, I’ve tried to find archives to do with Dr. Rey and there’s just nothing, absolutely nothing.

So Bernadette has gone back through every piece of evidence she’s amassed over the last seven years.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

This is a reply to a man who had questioned Time Magazine who had done an article on Vincent van Gogh and talked about him having cut off his whole ear. This man said, “No, no, no, he only cut off the lobe. Everybody knows that, Paul Signac said so”. And this is from the editorial offices and it says, “when Irving Stone, the author of Lust for Life was in Arles, he visited Doctor Felix Rey. Doctor Rey was the only man still alive who had seen Vincent van Gogh without his ear.”

In 1934, novelist Irving Stone wrote Lust for Life a biography of Vincent and his time in Arles. Although a work of fiction, glamorized further as a Hollywood blockbuster, Bernadette has discovered that Stone was rigorous in his research for the book.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

This letter says something extraordinarily interesting. It says “Doctor Rey drew a medical diagram for Irving stone on one of the prescription blanks which he later signed and which Mr. Stone now has in his possession, indicating that Vincent made a clean stroke cutting off the whole cabbage,” - I mean that’s the funniest line – “leaving nothing but the lobe”.

This is dated 1955 so what I need to know - is Doctor Felix Rey’s medical diagram still somewhere?

Bernadette had ignored this modern letter, but if Dr. Rey’s diagram exists, could it solve the Van Gogh mystery?

To find out, Bernadette must make the 6,000 mile journey from southern France to San Francisco.

The University of California Berkeley is home to Irving Stone’s archive, which Bernadette hopes will include a crucial piece of evidence.

The archive is housed in the Bancroft Library where she’s come to meet David Kessler.

Bernadette

Dr. David Kessler

Bernadette Murphy

David Kessler

So this is Berkeley.

This Berkeley, this is the Bancroft, yes

Beautiful, isn’t it?

Huge amounts of research material. Bancroft has hundreds of boxes like this and hundreds of cartons which are bigger, filled with material, but for Lust for Life he just had - he discarded stuff as he went along. So only a very few things exist, so all of it fits in this box 91 of the collection.

And in this, there are mostly letters that he collected for research. I know you’re gonna be excited to see this, see the kind of things you’ll see here - little brochures and clippings from newspapers. And eventually you find this tiny little document here.

Bernadette Murphy

David Kessler

Bernadette Murphy

David Kessler

Oh my godfathers!

And it’s from Doctor Rey and he says here - you know, in the subscript here, anything you can do to…

I’m gonna lose it. I’m sorry, I worked so hard on this, I can’t believe it, I can’t believe it after all these years!

This is from Dr. Felix Rey; it’s dated 18th August, 1930. I can definitely say that’s his signature. And it’s, it’s unbelievable. It says, “I am so happy to be able to give you some information that you asked me concerning my unhappy friend Van Gogh. I do hope that you will, you will glorify him as he deserves. The genius of this remarkable painter. Cordially yours, Dr. Rey”.

Bernadette Murphy

David Kessler It shows sort of a little sketch of an ear, and it says, “the ear was cut with a razor following the dotted line, and the aspect that is left of the lobe of the ear”.

That’s what it looked like afterwards – what his ear looked like. Just a tiny little bit down there. So it really documents that he removed his whole ear. It must have been an incredibly painful thing to do. “What was going through his mind at that time must have been remarkable.

Well you realize what a, what a really gruesome thing happened.

I’ve been working, I think as you know, on this for some time and when you finally get to - see something….

And this proves -

This – yes, it does prove exactly what happened.

Consuming seven years of Bernadette’s life and the subject of speculation and debate for over a century, the truth about Van Gogh’s ear can finally be revealed.

By the night of December 23rd, it had been raining solidly for three days.

Stuck in the Yellow House the whole time, tensions between Van Gogh and Gauguin mounted.

Gauguin announced his departure, and a heated argument ensued. Van Gogh hurled insults – “black lion”, “serpent”, “murderer.”

As Gauguin left, walking across the Place Lamartine, Van Gogh followed him and the confrontation continued. Vincent then returned home and, alone with his demons, took out a razor, held it to his head, and with a downward slice, cut off his entire ear.

For anyone other than Bernadette, Dr. Rey’s drawing would be the end of the mystery.

But what Vincent did next is also a mystery.

He left the yellow house staggering to the heart of Arles’ red light district.

At a brothel, he asked for a girl named Rachel, and handed her his severed ear.

For Bernadette, this extraordinary act was as intriguing as the ear-cutting itself.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

This street is Rue Bout D’Arles, the street that Vincent van Gogh came to on the night of 23rd December 1888. And basically he came across the park, walked up the street and went to the brothel.

All the research suddenly comes to life. You can imagine the catcalls going across. Drunken men, and girls trying to entice the men in and the general mayhem of a loud, bawdy part of town.

On the night of 23rd, when Vincent came here, his mind wasn’t on sex.

Instead, he asked for a specific girl, Rachel and gave her his severed ear with an almost biblical request to ‘take this in remembrance of me’.

So who was Rachel? And why did he single her out? Bernadette is now determined to track down her identity.

Once again, the city archives could provide evidence.

Prostitution was a legal profession at the time and sex workers were included in the city’s census.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

This is the 1886 census for the town of Arles as opposed to the outlying villages. And I have to look for section E which is where most of the brothels were located.

So I’m looking for the profession of lemonade seller – “limonadier” - and that was the quaint term. It could well be a lemonade seller, but it was the quaint term employed by people to talk about the brothel madams.

Ah, here we are, this is my girl - Virginie Chabaud, limonadier. This is the woman who was running the brothel at the time Vincent asked for Rachel.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator When I look at all the girls, one’s from Spain, this other lady is from Germany. You can see the ages 26, 29, 25 30, 30, 28 - these are not young women.

They’ve got lots of names - Jeanne, Rose, Marguérite, Marie, Madeleine - but there are no Rachels here.

Although there is no one by the name of Rachel in the census, Bernadette is still convinced that her identity is significant. After all, Vincent had a long history with prostitutes.

Stephen Naifeh, Biographer

He was horny basically and he was lonely, so he was desperate both for the sexual relationship and for the affection and nurturing that he desperately longed for in a relationship from a woman.

Vincent had even lived with a prostitute, Sien Hoornick, for a year and a half in Holland….

Could he have been similarly attracted to another, the mysterious Rachel, when he was in Arles?

Out of all the Arlesienne women whom Vincent must have encountered during his stay, what made her so special?

Bernadette couldn’t find any Rachel’s in the town census, but then she discovers something that changes the story completely.

It’s an old press article quoting the policeman who was actually at the scene of the crime.

In it he says, “the ‘prostitute’s name escapes me, though her working name was Gaby.”

For Bernadette, it is a pivotal detail. She goes back to the records and finds a document listing prostitutes. Many of the names were followed by the words ‘dite Rachel’ ‘called Rachel’.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

It’s not their real name! It’s just a nickname. I know they have other names like Blondie and Redhead and silly things like that, but Rachel is one of the names that occurs linked in to different girls. So maybe although policeman Robert said Gaby was her working name, maybe he just got it wrong. Maybe it was her real name.

There were no Rachels living in Arles in 1888 but there were thirty-one women called Gabrielle or Gaby.

Bernadette is determined to track down the identity of this key figure in the drama of Vincent’s breakdown and now, she has another fascinating lead.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

This book is by a man called Leprohon and what’s really interesting is that he does a sort of follow up after Vincent’s death and goes back over the tracks of Vincent trying to find different testimonies and different places where he lived.

There’s things on Madame Ginoux, there’s things on the Roulins. And all various different people in the life of Vincent, but what’s really interesting is towards the end of the bookthere are just four little lines, but to me they’re really exciting!

It says Rachel, who was called Gaby, died in 1952 at the age of 80. So what I have to do is find anybody called Gaby who died around the age of 80 in 1952.

For Bernadette, the information raises new questions. Until now, many assumed Vincent’s Rachel or Gaby was a prostitute, simply because she worked at a brothel.

But if Vincent’s Gaby died in 1952, she would have been sixteen at the time of the incident, five years below the legal age for prostitution.

Bernadette has discovered there was one Gabrielle of the right age, who died in Arles around that time.

With a network of connections, she finds one local who

is willing to give her insider knowledge.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

Michèle Audema, friend of Bernadette Murphy

Bernadette Murphy

Eh euh, et vous connaissez la famille?

And you know the family?

Oui, bien, oui, ça fait – oui, oui.

Yes, quite well.

Ils sont connus sur Arles.

They are well known in Arles

Ca c’est super intéressant, Michèle, super intéressant!

This is really interesting Michèle!

Oui.

Gaby’s family still lives on the outskirts of Arles and agreed to meet with Bernadette.

But sensitive about their family secret, they did not want to be filmed.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

The family do not wish in any shape or form for their identity to be revealed. The perfume of scandal that surrounds the notion of working in a brothel is too much. People were prostitutes. She wasn’t, she was a cleaner, she was a domestic servant in a brothel and she did several brothels in the street by the looks of it.

Although keen to remain anonymous, the family have revealed a potentially vital connection between Van Gogh and Rachel.

In 1888, both she and Vincent were in Paris at the same time.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

When I was down in Arles I thought that I’d finished the story of Rachel, but then I discovered that she had actually spent the early part of January 1888 here in Paris, and what’s really extraordinary is she was actually treated by Louis Pasteur himself.

In 1885, the great French chemist discovered the cure for rabies.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

So the medical records give me her name, Gabrielle that she came from Arles and that on 8th January 1888 at 3 o’clock in the afternoon she was bitten by a dog that had rabies. She was literally put on a train that night to Paris – it was a whole day and night journey - and she started treatment on 10th January and this continued to 27th January.

Although Vincent and Gaby were in Paris at the same time, the chance of them meeting in a city of 2 million seems unlikely. Until Bernadette remembers something from one of Van Gogh’s letters.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

I started to get a little bit intrigued because I found some references. There are two references to Pasteur in Vincent’s letters. But one in particular is very, very precise. It’s a letter that he wrote sometime around 9th or 10th July, 1888 and he says that the women who go around having been bitten by rabid dogs, who live at the Institute Pasteur.

Did Vincent learn about Pasteur from these women in Arles or, more intriguingly, from an encounter with the mysterious Gaby in Paris?

Vincent arrived in Arles just three weeks after Gaby returned from her treatment.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator I wonder if they did meet while she was in Paris? I mean, there was no reason for Vincent to go to Arles. He did want to go south we knew that. I think that perhaps he followed her there.

If Bernadette’s theory is correct, she has possibly discovered why Vincent went to the brothel on that terrible night: To give his ear to the girl who’d attracted him to Arles in the first place.

Now Bernadette has one final journey to make. She’s heading back to where she started: the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, with a copy of her evidence.

Bernadette Murphy, Investigator

Louis van Tilborgh, Senior Researcher, Van Gogh Museum

Teio Meedendorp, Senior Researcher, Van Gogh Museum

Louis van Tilborgh

Bernadette Murphy

So I have something to show you.

It’s dated the 18th of August 1930 – Ie checked the address, I checked the signatures. Have a look and tell me what you think.

Well, that’s answered a question.

There’s not much left of the ear at least. In this drawing it’s quite clear on what happened.

The truth now is in front of our eyes. You did find an important document.

Thank you, Louis. I was excited when I found it. It answers a question. And it was the question I had in the beginning. It just took, you know, a much longer time to bring – to prove it in the end than I thought.

It answers it for once and for all.

It answers it for once and for all, yes. Kind of a lucky find for Bernadette!

Bernadette’s seven-year quest has created an incredible picture of Van Gogh’s time in Arles. The people he knew, where they lived, his friends, and his enemies.

She has tracked down the girl he gave his severed ear to – and even found a possible explanation for why Vincent was drawn to Arles in the first place.

In the Van Gogh Museum, the artworks and documents that tell this story are now coming together for the first time in a major exhibition that re-writes the legend of Vincent’s descent into madness.

The exhibition includes the brilliant portrait of Dr. Felix Rey and the still life showing his brother’s letter that could have pushed him over the edge.

Tucked among the masterpieces, there is even a tiny scrap of paper, forgotten for over half a century: a small drawing by Doctor Rey that finally solves the mystery of Van Gogh’s ear.