The trouble in Salem began during the cold, dark Massachusetts winter, in January of 1692. Eight young girls began to take ill, begining with 9-year-old Elizabeth Parris, the daughter of Reverend Samuel Parris, and his niece, 11-year-old Abigail Williams. But theirs was a strange sickness: the girls suffered from delirium, violent convulsions, incomprehensible speech, trance-like states, and odd skin sensations. The worried villagers searched desperately for an explanation. Their conclusion: the girls were under a spell, bewitched — and, worse yet, by members of their own pious community.

The trouble in Salem began during the cold, dark Massachusetts winter, in January of 1692. Eight young girls began to take ill, begining with 9-year-old Elizabeth Parris, the daughter of Reverend Samuel Parris, and his niece, 11-year-old Abigail Williams. But theirs was a strange sickness: the girls suffered from delirium, violent convulsions, incomprehensible speech, trance-like states, and odd skin sensations. The worried villagers searched desperately for an explanation. Their conclusion: the girls were under a spell, bewitched — and, worse yet, by members of their own pious community.

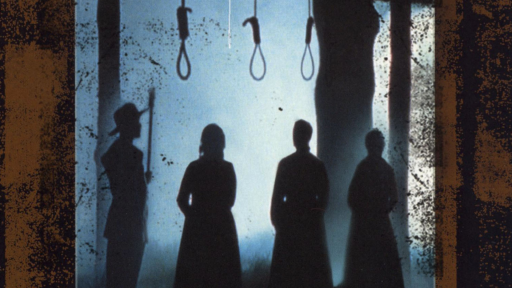

And then the finger pointing began. The first to be accused were Tituba, Parris’s Caribbean-born slave, along with Sarah Good and Sarah Osburn, two elderly women considered of ill repute. All three were arrested on February 29. Ultimately, more than 150 “witches” were taken into custody; by late September 1692, 20 men and women had been put to death, and five more accused had died in jail. None of the executed confessed to witchcraft. Such a confession would have surely spared their lives, but, they believed, condemned their souls.

On October 29, by order of Massachusetts Governor Sir William Phips, the Salem witch trials officially ended. When the dust cleared, the townsfolk and the accusers were at a loss to explain their own actions. In the centuries since, scholars and historians have struggled as well to explain the madness that overtook Salem. Was it sexual repression, dietary deficiency, mass hysteria? Or, could a simple fungus have been to blame?