TRANSCRIPT

Narration

Queens, New York.

Construction workers discover the body of a young woman.

At first, it appears to be a homicide.

But something about the scene doesn’t quite add up.

Scott Warnasch

My colleague was finishing off sweeping away the last residue of the soil

That’s when he discovered something kinda shocking.

Narration

Now, forensic archaeologist Scott Warnasch wants to piece together this historical puzzle.

With the help of a close-knit New York community…

Rev. Detherage Esq.

We can identify with her because she does look like us. And so, it does make it personal.

John Houston

It was my honour to complete that circle

Narration

…Leading scientific experts…

Dr. Rhonda Quinn

Lots of different chemicals that are captured in her teeth that told us a little bit more about how she lived.

Narration

…And cutting edge technology…

Scott Warnasch

This is unbelievable I have never seen anything like this before

Narration

…We open the door to a neglected history…

Joe Mullins

It’s like a digital – you know - puzzle that we are piecing together

Prof. Carla Peterson

It is really important that we create this rich and diverse tapestry of African American life in the 19th century

Narration

…To reveal the mystery behind…

…The Woman in the Iron Coffin.

Detective Davies

This area right here is north Queens, Corona Elmhurst border.

Detective Saenz

Middle class. Not a bad area.

Detective Warren Davies

It’s a mixed population here. A lot of local businesses, not really a bad place in terms of crime.

Crime can happen anywhere,

In my career i’ve seen over a thousand homicides.

You get a little bit numb to it, but it doesn’t get easier.

Detective Robert Saenz

To be called out for a D.O.A. in this area is not really that uncommon but it’s not a frequent event in this area.

[Phone ring tone]

[Emergency operator]

“911 emergency”

Narration

On October 4th, 2011, construction workers at a site in Queens made a grim discovery.

Detective Saenz

We received a call at Crime Scene at about 9:15 in the evening.

Detective Warren Davies

It was a D.O.A. and it was deemed that they discovered under suspicious circumstances,

The workers at the construction site were working with the heavy equipment and they hit something, which they believed was a pipe, and they saw an individual in it and that’s when they decided to call the police.

Narration

Detectives Warren Davis and Robert Saenz were two of the first responders.

Detective Warren Davies

What we had when we came to the site, we found it was all ply-wooded up

It was dark, there was no lighting and in the background what we had was a field, and we could see it barely with our flashlights, but we knew down in the pit area was where this backhoe unearthed this individual.

Narration

But what at first seemed like a recent homicide, soon became something much stranger.

Detective Davies

There was some metal that was very intriguing to see

Detective Saenz

What they did see over there obviously was very unusual. It was surprising to see how well preserved the remains were.

Narration

Who did these remains belong to?

My name is Scott Warnasch, I am a forensic archaeologist.

I spent a lot of my early career in archaeology, working on traditional archaeological sites - historic and prehistoric - and I gravitated towards excavating skeletons and cemeteries or burial grounds. I was always interested in forensics although I was very squeamish and I didn’t think I would be able to get through the proper coursework to get that formal degree.

‘54

Scott Warnasch

I originally began working at the medical examiner’s office in the World Trade Centre, handling the remains, doing the case file work and releasing the remains to the family members.

Recovering potentially human remains and identifying the victims, puts my usual work at a much higher level of satisfaction than typical archaeological projects.

Scott Warnasch

October 5th 2011, it started off like a normal day, although a normal day at the medical examiner’s office is probably a bit different than everybody else’s.

When we got to work, we were told that we had to get a crew together for the forensic anthropology unit to respond to a potential crime scene in Queens. Apparently, a body was discovered in Elmhurst.

So, we arrived at the scene on Corona Avenue, walked into the site and spoke to the detectives to get a little background on the situation.

The team lines up as we approach the scene, and we’re looking on the ground, looking for any type of evidence that may have been dug up from the machinery and spread around the site.

It was then when I noticed this piece of rusty metal.

It wouldn’t have been anything to anyone else on the site, however I had some idea of the significance of it.

This told me that this wasn’t an ordinary crime scene. This suggested that the person died over 150 years ago.

As we were uncovering the body and exposing it, we quickly realized that we were dealing with an African American woman.

She seemed to have been buried in some kind of white nightgown and high, thick knee socks.

Forensic protocol suggests that you leave the most sensitive parts of the body covered until the last minute. That way they’re protected from the sun or any other situations.

My colleague Chris was finishing off sweeping away the last residue of the soil around the woman’s chest and around her face.

That’s when he discovered something kinda shocking.

And as he’s sweeping away, we can see these lesions all over the top of her chest and on her forehead.

It looked a lot like smallpox.

So, the situation went form a potential crime scene to an archaeological discovery to a potential biohazard within like an hour.

So, there were two things that we needed to do right away.

One was to take extra precautions when handling the body and messaging that down the line to the morgue so everybody involved with this understood what we were dealing with.

The second was to call the experts.

Dr. Kevin L. Karem

My name is Kevin Karem, and I am a medical researcher, and I work for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia.

My career and my role at the CDC over the years has been as an infectious disease researcher. So really helping to protect the public health of the country and we actually have an extensive global program as well.

Dr. Kevin L. Karem

Within days after getting the call from Queen’s County we prepared to come up to New York and help them with the case. We thought well there is no way that we are going to find anything viable.

And so, we agreed that we would be quick and brief; we’d take a few specimens externally and move on. Well that changed the next morning when we got to the morgue.

One of the more shocking things for me was actually opening the body bag and seeing the sheer number of lesions across this young woman’s body from head to toe. The preservation of the body was just totally unexpected

And so that point I got a little more nervous about the possibility that there might be a contagion risk here.

Smallpox is very unusual, in that it is thought to have killed more people in human history than any other agent that we know of.

It was transmitted by aerosol droplets. So, when someone had a cough or sneezing it could actually be carried on those particles in the air and that’s thought to be one of the reasons why it was so contagious.

Its transmission rates are around 60%, which is actually higher than Ebola. The mortality rate, depending on the outbreak, could be anywhere from 10-60%.

But it’s very devastating and, the denser population and community, the higher the probability of spread.

Dr. Jeffrey Kroessler

We tend to forget that in the cities of the early 1800s, to, even throughout the 19th century, there was a very active disease environment and you didn’t have great sanitary conditions.

Prof. Carla L. Peterson

New York was an incredibly unhealthy place to be in the 19th Century.

There are waves of epidemics that sweep the city against which the population you know has no recourse. And it attacks those who are living in the least healthy environments.

And that was where African Americans of course were allowed to live

Death by epidemic was absolutely very common

Narration

By the middle of the 20th century, there was a huge effort to wipe out small pox once and for all.

Dr. Kevin L. Karem

In 1959 there was a World Health Assembly meeting where they talked about mandatory vaccination program to eradicate the disease.

So, disease in the United States was eliminated really before 1970. Vaccination among children of the United States actually stopped in 1973 and then the rest of the world followed suit. And then in 1980 the World Health Organisation declared the world to be smallpox free.

Scott Warnasch

Although we understood that this woman probably died over 150 years ago, it was important to examine the body to determine whether this was a public health concern.

Dr. Kevin L. Karem

So, in this case the type of specimens we took from skin tissue as well as internal organs were very good samples for a test we call called Polymerase Chain Reaction, or PCR.

And in that test, we can actually look specifically for viral DNA sequences based on what we know about smallpox virus.

And it was the most effective way for us to test quickly.

What we found was that we could not detect any DNA.

And what it really told us that the tissue and any viral DNA was degraded. Probably due to how long it had been since she had died, the moisture in the body, that sort of thing.

We felt confident at that point that there was not a contagion present, and that the body really posed no risk relative to smallpox.

With the results from the CDC showing there was no public health threat, Scott’s part of the job was officially over.

But he couldn’t let the case go.

He wanted to know more about this woman and the world she inhabited more than 150 years ago.

And so, to help him solve the mystery, Scott turned to science.

Scott Warnasch

I was able to get in touch with a specialist on non-invasive ways of examining a body.

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

My name is Jerry Conlogue and I’m emeritus professor of diagnostic imaging and co-director of the Bioanthropology Research Institute at Quinnipiac.

I guess you could say I’m a mummy man.

I’ve probably x-rayed well over a thousand mummies in maybe 16 different countries.

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

For me, the real excitement, and I still feel this after 40 years of doing mummies: to be able to use x-ray to find out what’s inside the mummy.

An individual’s skeleton is kind of record of what their body was like, from when they were an infant until when they died, so the history is definitely in the bones.

My job is to be able to get that information out of the bones so that it can be interpreted by someone like Scott, an anthropologist.

Scott Warnasch

This is unbelievable I have never seen anything like this before. We’ve seen x-rays, we’ve seen some CT scans, but this is a 3D version of this woman.

Narration

The original CT scans Jerry made of the woman have been loaded into a piece of groundbreaking software.

It allows for a “virtual” autopsy of the body, unlocking the secrets contained within without making a single incision.

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

Normally I am looking at sections or regions of the body, but this thing lets me see the entire body and I can spin it and roll it and go into it and come out of it. This is a way that I have never been able to look at a body before.

Narration

With just the swipe of a screen, it can move between multiple layers of the body—

digitally stripping back skin, revealing internal organs, and showing the skeleton beneath.

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

If we had examined her let’s say in 2000 we would have not have had the capability with the CT and the MR and this wonderful table would have not been there.

Scott Warnasch

Yeah, right. We would have X-Rays.

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

We’d just have plain X-Rays

Scott Warnasch

Typically, in an archaeological situation you never really know how someone died, the cause and manner of death. Based on what’s left is usually the skeleton unless they have a bullet hole or an arrowhead in them. Here we can see clearly the cause and manner of this woman’s death is smallpox.

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

Well on the surface, you can see all these small pox lesions on her head, on her neck, on her chest, down into her thigh area and even down into her feet.

Scott Warnasch

And then on her heel, then on the pad of her foot, on the ball of her foot.

Dr. Kevin L. Karem

Typically with smallpox the rash really initiates in the mouth, in the oral cavity, and so, they become really sore, you have lesions inside your mouth, and then it becomes a full-blown skin lesions in a centrifugal pattern – that means predominantly in the limbs but also on the trunks.

And quite often it was documented that they would have you know exceptional fever, immune response and then a significant drop in blood pressure, which indicates some type of organ failure

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

I would have only expected lesions on the surface, but if we look inside her skull, this is her brain. Now covering the brain there is this tissue that is very dense it is kind of a consistency of canvas and that’s to protect the brain and that is called the dura and there are lesions on the dura.

What makes this really unusual is that I don’t think anyone has ever imaged an individual with smallpox, looked inside. And here we have evidence that the lesions are in fact inside.

Scott Warnasch

It is amazing. It is like we have a map of how smallpox colonised the human body. That’s a first. That’s a medical first.

Narration

The woman’s body was so well-preserved, the smallpox that killed her remains clearly visible… something Jerry and Scott wouldn’t usually get to see from skeletal remains.

Narration

The airtight coffin perfectly preserved the woman.

Scott Warnasch

The iron coffin was invented by Almond Dunbar Fisk. He was originally a stove manufacturer in Lower Manhattan.

In 1844 Almond Fisk’s brother William died in Mississippi during the summertime and there was no way to transport his body back up to New York. This caused a lot of sorrow for his family and especially his father, and this seemed to be the instigation for the development of the coffin.

Dr. Jeffrey Kroessler

If you died far from home in the early 1800s, that is where you were buried. You are not going to be transported – a corpse - hundreds of miles over weeks or months. That is out of the realm of possibility. You will be buried where you fell.

Narration

In the age of steam travel, Fisk’s iron coffin was invented to address the issue of people dying far from home.

The coffins were designed to preserve bodies for sanitary storage and long-distance transportation.

If someone died far away, he or she could now be sent back home for a proper burial among kin.

Scott Warnasch

He bought a large farm outside of Newtown, Queens and in one of his barns he set up a little furnace for himself and started his own foundry and started experimenting.

Narration

Today, the Fisk Avenue subway stop on the number 7 line stands a short distance from the location of the 19th-century foundry.

Scott Warnasch

In 1848 Almond Fisk was granted the patent for his metallic burial case and started a company with his brother in law William Raymond, the company being Fisk & Raymond

Scott Warnasch

We’re here at the Canton Historical Society Museum in Collinsville, Connecticut. They have the most extraordinary example of a Fisk metallic burial case

There are so many little details that you never get to see from the iron coffins that get excavated from archaeological sites. There’s so much care and craftsmanship in this that it’s just unbelievable.

Although they’re considered a manufactured from a factory product, this was the 1840s and 50s, and it took a long time to finish one of these.

So, it was sort of maybe a bit of an assembly line, but it wasn’t like they were being pumped out like chocolate bars or anything like this. This was still a product of many craftsmen and many hours of work.

This coffin was invented prior to modern embalming. This was the closest they could get to some way of preserving the dead for transportation and storage.

The coffin body itself would be cast in the sand, however certain parts of it were manufactured separately as sort of like medallions and could be pressed into the sand mold to show these different motifs.

So, the face plate, the nameplate and the footplate.

They had some variation, they had choices on what they wanted to represent on the coffins.

A very important feature of these coffins of the time was that it also had a window for viewing the deceased. This was a time before photography had really caught on as a mode of identification. And it was important for the next of kin to be able to view the body and determine that it was in fact them.

They had some variation, they had choices on what they wanted to represent on the coffins.

A very important feature of these coffins of the time was that it also had a window for viewing the deceased. This was a time before photography really caught on as a mode of identification. And it was important for the next of kin to be able to view the body and determine that it was in fact them.

Narration

The Fisk iron coffin was completely airtight.

A body sealed inside was kept so well-preserved, it would be recognizable for the purpose of legal identification.

Scott Warnasch

Once the viewing was over, the lid would be put back on and bolted shut. And theoretically the whole coffin would be airtight at this point.

The foot of the coffin is probably the most important part for the marketer and inventor, Almond Fisk.

This is the patent mark that was granted to Fisk on November 14th 1848. It says, “A. D. Fisk, patent, November 14th” and then a 48 in the centre.

Scott Warnasch

The coffins were a marvellous invention to preserve bodies for transportation.

As an archaeologist, most of the time all you’re expecting to find are skeletons in varying degrees of preservation.

But in this case, oh my god! We have everything here; this woman is so preserved.

Narration

Most bacteria and organisms responsible for bodily decomposition require oxygen.

But in this case, it was difficult for them to do their job, because the iron coffin was airtight.

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

I’ve certainly never seen a body that is in this state of preservation, that has not been artificially embalmed.

What I am seeing here is her liver. The liver would be the first organs that will probably start to decompose. So, decomposition was stopped, so that speaks to the efficiency of the coffin.

Scott Warnasch

The coffins were very expensive for the time, they came in many sizes and they were generally associated with the rich and the elite.

In 1849 former first lady Dolley Madison passed away and she was one of the first famous people to be buried in a Fisk coffin.

She was a very well beloved American icon at the time. Her funeral was covered in all the papers and the fact that she was in one of these coffins, shortly after they were patented put Fisk and Raymond into a much larger world.

Many more famous politicians, Henry Clay, President Zachary Taylor, Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, even President Lincoln’s son Willie was preserved in a later version of these coffins when he died while the president was still in office.

When we were originally discovered the woman in Queens and it was revealed that she was African American that was quite a shock because that certainly didn’t fit the pattern of who you would expect to be in one of these elaborate coffins.

Once we understood she probably died of smallpox that sort of started to make sense why she might be quarantined in one of these coffins, however how she got the coffin would still remain a mystery.

Scott Warnasch

So, what we have here are a bunch of photos of coffin fragments that were recovered from the scene.

I spent some time trying to put it back together, and it turned out we had about 50 or 60 fragments, but not the whole coffin.

However, the most important part of the coffin was recovered.

It was the most important part because it had the patent mark.

Most of the patent marks that Fisk put on his coffins are aligned a specific way on the foot and are rotated in a way that you can read them easily, and that’s just his logo at the time.

However, this coffin is significant because the patent mark is misaligned, and the whole logo is rotated 180 degrees, so it was pretty much botched.

Everything about it worked, except that the main marketing part of it was messed up.

So maybe it was put to the side and saved for a time of need.

Scott Warnasch

By understanding this one woman, she provides a window into the time that she lived in, we can learn a lot about the environment, her living conditions, maybe even the types of work she did and from there we can extrapolate into the larger population of the African American community.

Prof. Clarence Taylor

In trying to reconstruct the lives of African Americans in the 19th century and earlier, we face several challenges.

Many African Americans didn’t read or write so they didn’t leave their memoirs or their stories behind. In addition, many white historians did not record the histories of African Americans; they were essentially ignored.

Scott Warnasch

The first step in an identification process is to create a biological profile, and as an anthropologist, we would use the skeleton to start to narrow down potential candidates of who this might be, based on relative age range, their sex, potentially their ancestry and their stature, and through that, you come up with a thumbnail sketch about who this individual is.

From the skeleton you can learn a lot about the age of the individual based on how well the bones have been formed, and how they have developed. The long bones have these caps and if the caps at the ends of the bones have fused then we can understand that this person is an adult.

Then we also have the spine.

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

Yeah, she has some arthritic changes, this lipping on the ends of the bones, so as arthritis develops you’ll get a bridge or excess bone formed because of the wearing action on the bone. She has got minimal, so I would say she’s probably over 25 but I don’t think she is really that old. I don’t think she’s much older than 30.

Scott Warnasch

And we can see a little bit of arthritis in her lower back. It does suggest she probably used her back on a daily basis.

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

These folks had a physical life. So, if you are bending over a lot, unfortunately this is the part of your spine that is going to show these early degenerative changes

Scott Warnasch

The skeleton isn’t suggesting she did a lot of lifting or carrying. If somebody had a life of extreme manual labour, working in the fields I think that would be showing up on a body, even this age.

As you can see here unfortunately the woman’s face was pretty damaged by the construction equipment when she was discovered.

The damage to her face is just incredible

Prof. Jerry Conlogue

The right side of her face doesn’t look too bad but the left side.

This area here where you’ve got a fracture through the cheekbone, fracture through the jaw and when I roll this back and forth - and it is one of the beauties of this table - her right ribs look okay but her left ribs are fractured

Scott Warnasch

While we are in this view I get to mention an article of clothing that is really fascinating on a lot of levels.

It’s an exquisite comb carved out of either horn or maybe tortoise shell. It’s beautiful, almost a nimbus cloud of knots over 12 long, straight teeth. This would have been a hand carved comb. It was placed in the back of her hair, it held her hair back and also held a very delicate knit cap that was on the back of her head.

And it shows really personal aspects of her life. It has got little nicks in it; it’s got polishing in certain areas. The little day-to-day motions that this woman had in her life.

And it also represents in a large way, the larger community that was involved with preparing her body for the funeral, that they took the time to put her comb in and put the cap on her head and prepare her for a proper burial.

Scott Warnasch

Within the time the woman lived it was a very tumultuous period for African Americans in New York, as well as everywhere else in the country.

Prof. Clarence Taylor

America was an emerging nation, it was not the superpower that we think of today.

The economies were diversifying. By the 19th century slave labour was diminishing in the North whereas it was growing and became quite valuable in the South

Prof. Carla Peterson

There are great differences among African American communities in terms of geography whether you are in the North or in the South or in the West.

In the North the first state to abolish slavery is Vermont, and Vermont is 1777, followed by Pennsylvania and Massachusetts.

Prof. Clarence Taylor

New York was one of the largest slave holding states in the United States. Proportionately surpassing some of the southern states

By 1788, four in ten New York families owned slaves

Narration

New York was one of the last states in the North to abolish slavery.

Prof. Carla Peterson

It’s a somewhat complicated procedure. In 1799 a gradual emancipation bill is passed which says that slaves born before July 4th 1799 are slaves for the rest of their lives, but people born into slavery after July 4, 1799 will be emancipated.

In 1817, another bill gets passed that declares that people even enslaved before 1799 will be freed on July 4th 1827.

Narration

Finally, on July 4th 1827, 28 years after the state’s first emancipation bill, New York’s African American community celebrated their liberation.

In all, about 10,000 people in New York state were set free.

Prof. Carla Peterson

The position of the African American community remains very vexed because you do have slave kidnappers coming from the South up North in pursuit of slaves who have escaped to the North and the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 meant that they could indeed legitimately go and catch slaves and bring them back.

But the real problem is that the kidnappers would come up and were capable of seizing any black off the street and saying ‘oh you are a slave, you are the slave of Mr Johnson whoever and we’re remanding you into slavery’ and that person could protest and say ‘well no I’m free’ and ‘I was born here free’ etcetera, but if you didn’t have your papers on you right then or you couldn’t prove it on you right then and there, you were kidnapped and sent into slavery. And that was a process known as ‘black birding.’

One great example is the case of Solomon Northup who was a free black and who was kidnapped and taken to the South, and was twelve years a slave, and lived to gain his freedom and to write that narrative.

Prof. Clarence Taylor

After emancipation in New York, the abolition of slavery in New York, the black population was made up of free African Americans; it was also made up of people that had escaped slavery and had come to New York, as well as those who had been manumitted from slavery.

Narration

Throughout New York, free African Americans established their own communities.

Weeksville in Brooklyn and Seneca Village –later cleared to make way for Central Park—were among them.

Scott Warnasch

New York was a magnet for escaped slaves to migrate north.

What I am really interested to find out is if this woman was a freed slave, an escaped slave, or from a family that had been freed for quite a long time.

Narration

Comparing when the coffin was manufactured and her age when she died, this woman must have been born sometime in the early 1800s.

If she was indeed born in New York after the Emancipation Act of 1799, then it is more likely that she was a free woman rather than enslaved.

Scott Warnasch

One of the best ways we can determine the origin of the person - where they were born - is isotope analysis.

Dr. Rhonda Quinn

My name is Rhonda Quinn.

I am a biological anthropologist. I am a professor at Seton hall University and I use geochemistry to answer anthropological questions.

If you are looking to paint a picture of where someone was from – the place of origin throughout the time period of their childhood, even into the late childhood, teeth are the best place to go. Teeth are amazing snapshots of time in your life and the environment itself, it tells you about diet, it tells you about location.

Narration

Adult teeth begin to develop before birth and continue growing until they are all in place.

As they grow, they absorb the chemicals found in the water the person drinks. These chemicals are unique to geographic regions.

Dr. Rhonda Quinn

The first measurement that we did was oxygen isotopes. Really what this is showing us is what was the signature of the water that she ingested,

What we first found was that, she would have ended up in this blue part, and what do you know, it absolutely overlaps with New York.

Scott Warnasch

So, it’s like a snapshot of her childhood environment?

Dr. Rhonda Quinn

Absolutely.

I cannot differentiate her from people who resided in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania.

It’s really only the southern states that I can take out. So only Florida, Alabama, Georgia.

Narration

Specific isotopes found in the tooth match the mineral content of the water in the northeastern United States, meaning she can’t have grown up in the South.

Dr. Rhonda Quinn

The other component we really wanted to look at is lots of different elements in her teeth, lots of different chemicals that are captured in her teeth. They told us a little bit more about how she lived.

We measured lead. Lead was much higher than we would have predicted. You get lead levels this high when you have industrialisation

Scott Warnasch

That’s really interesting because just based on the general area of where this woman seems like she grew up, she was really close to industrial centres of Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan.

Dr. Rhonda Quinn

We have a few locations in the United States that show us that – New York is one of them.

Narration

While her teeth give clues about where this woman came from…

…a sample of her hair provides a window into how she might have lived.

Dr. Rhonda Quinn

This represents a different time period in her life. As you can imagine the hair on top of your head is growing at a rate that’s much faster and it’s going to represent a time period very close to her time of death.

A student of mine collected data from a number of New York City residents today. She looks like a lot of New Yorkers.

Scott Warnasch

So, does that mean she ate meat like most New Yorkers or protein at least?

Dr. Rhonda Quinn

For the time period that is represented with this hair sample, it looks like she’s getting a fair amount of protein –

Scott Warnasch

So, a fairly balanced diet then? OK

Dr. Rhonda Quinn

There’s probably a little bit of corn in her diet, but it’s not a corn-based system that we see in the United States today in Middle America. She looks like other New Yorkers.

Narration

The science seems to confirm that the woman grew up close to New York City.

But to identify who she was, Scott needs to work backwards from the place where her body was found…

…to piece together what Queens was like when she was alive.

Scott Warnasch

The coffin was discovered right here on Corona Avenue here right between Corona Avenue and the railroad tracks.

Obviously, Queens has changed considerably since the mid-19th century.

Trying to find out a little bit more background on what was on this property previously, we contacted the New York City Landmarks Commission.

Dr. Jeffrey Kroessler

What was Queens like in the decades before the Civil War? 1830s, 40, 50s?

You have a major town in Jamaica, which serves the southern half of Queens.

The other major town is Flushing.

And then there is Newtown – what is now Elmhurst.

What was Newtown like in the 1850s?

It is a small place.

This is a one street town and there was nothing beyond.

Scott Warnasch

The Landmarks Commission explained that the property where we discovered the body was the site of the African church right on Corona Avenue.

Originally it was called Dutch Lane and it had changed names a few of times over the period of the 19th century.

I was able to uncover the original deed for the Dutch Lane cemetery property, which was sold to the United African Society in 1828.

Narration

Only one year after full emancipation in New York, the African American community in Newtown established its own church.

Dr. Jeffrey Kroessler

The African American population who lived in Newtown were either the children of slaves or they were former slaves themselves.

But at this point, they are free people, who have sufficient funds that they are able to buy property for a cemetery.

There isn’t a lot of wealth in the African American community but they are able to build a church.

Prof. Carla Peterson

The African American community organised itself right from the beginning in very, very powerful ways

And the whole concept of mutual relief was really the bedrock of the African American community.

You come together in fellowship and brotherhood, and everybody puts in a certain amount of money and that is then reserved to help anybody in need.

And then you have black churches, black denominations like the African Methodist Episcopal church, AME church.

Prof. Clarence Taylor

The African Methodist Episcopal Church was a church that grew out of protest. African Americans in Philadelphia, who were members of the predominantly white Methodist church were essentially discriminated and asked to sit in segregated pews and they refused to do that and left and formed their own church the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and this took off and many other African Methodist Episcopal Churches formed as a way of sort of protesting racial discriminations and segregation in white churches.

Prof. Carla Peterson

Churches are engaged in political activism and one example would be the Amistad case, when a group of slaves who had mutinied on the Amistad come ashore.

And so black churches galvanised to send money.

So, churches are really important, not just from a religious point of view but from a social and political point of view.

Narration

Today, St. Mark African Methodist Episcopal stands just one mile from the original Dutch Lane church.

Its history can be traced all the way back to the community established by the United African Society of Newtown, more than 160 years ago.

Scott Warnasch

That church was notified when this woman was discovered, and they were invited to contribute their input on what should be done with the woman.

Rev. Kimberly Detherage

My name is Kimberly L Detherage and I’m the pastor at St Mark African Methodist Episcopal Church here in Jackson Heights, Queens, New York.

Narration

St. Mark A.M.E. Church moved away from the Dutch Lane location in 1929.

Rev. Kimberly L. Detherage Esq.

The woman that was found represents us. She was found in our African American burial ground and because of that she is a member of our congregation, and as a member of our congregation it was important for us to make sure that we treated her with the very, utmost respect, that her her her life and her body was not treated disrespectfully, but most of all that we paid homage to the person that she, that we believed that she was.

We had to hire a funeral home, and we wanted to make sure that there was an African American funeral director and a funeral home that would be taking care of her body, because we understood that as a part of our congregation, we wanted someone who looked like her and looked like us, to make sure that she was well taken care of.

I’m John Houston and I am a funeral director and I’m originally from a small town in north Alabama named Decatur.

I have been a funeral director for 23 years and this particular funeral home we serve the general north New Jersey area.

I got a call from the church, from St Mark A.M.E.

And I went to pick up the body and then when I saw her and the clothing that she had on and she was still intact, it was obvious that this was a historical case.

We brought her back here, we took her downstairs, and got an opportunity to look ourselves to see, and it was unbelievable. She was fully clothed. You could see the actual colour of the clothing and you knew that there was someone that had taken great care in preparing this woman for burial – the same thing that we do – and it was just unbelievable.

It was my honour to basically complete that circle - that she was being cared for again. I was honoured to take care of her.

We were her family during that time.

She was buried in a solid mahogany casket. There was a casket spray that gave a sense of Africa and nature, the choir sang. It was a service for a person, just as though that someone had died in the congregation today. There’s no difference.

It was totally unbelievable to me and probably i’ll never get this opportunity to take care of a case like this again.

It’s really part of the African American heritage. We did not come to this continent freely. We were stolen from west Africa and brought here treated terribly and still we are not treated fairly and to see someone who was actually clothed the way that she was and in an expensive casket, it gave us a sense of pride and also gave us a sense of pride to give something back and give her a great going home service.

Scott Warnasch

It is important to remember that this isn’t just an archaeological specimen; this is an individual who was a person that had a life.

One of the best ways to humanise her is to give her an identity.

I began the identification process using two criteria first based on the time the coffins were manufactured, and second the age range based on the woman’s biological profile

The date range for the coffin manufacturing began around 1848 to about 1854.

That gives us a nice window for the identification process to begin.

Narration

As luck would have it, this time period also gives Scott the perfect place to look for potential names: the 1850 census.

It was the first time African Americans were listed individually by name in the census—

the first full accounting of the African American population of Newtown.

Scott Warnasch

The biological profile of the woman gave an age range of between 25 and 35 years old.

Combing through the 1850 census came up with 33 possible candidates that fit the biological profile of this woman.

Narration

As Scott scours the census records, one name stands out.

Scott Warnasch

Her name was Martha Peterson and she was 26 years old in 1850.

Scott Warnasch

The census data lists Martha Peterson living with a man named William Raymond.

That’s amazing because William Raymond not only was Fisk’s brother-in-law, he was also his next-door-neighbour and business partner.

Now we have the name of a woman that fits the biological profile who was living with the maker of the coffins.

If this woman was Martha, it’s an easy jump to conclude that if Martha died of smallpox in the house of William Raymond then she would be buried in one of his coffins.

He would be the perfect person to be able to supply the remedy to handle this situation.

And the fact that the patent mark was misaligned and sort of botched may suggest why it was available at the time of Martha’s death.

The woman’s clothing suggests that she was taken care of and was dressed properly for a burial.

So, the question becomes who did care for her? Potentially family members; that would be the most likely explanation

I have been looking at the 1850 census and established that there are five main branches of the Peterson family. Five males are all within the age range of who would have been Martha’s parents’ generation.

I have narrowed that down to one particular couple, John and Jane Peterson.

Narration

Scott believes the key to identifying John and Jane as Martha’s parents lies in the name of one of her potential nieces.

Scott Warnasch

If Martha was the daughter of John and Jane Peterson that means that Martha had a brother named Elisha.

Elisha had a daughter that he named Martha. This is the only other Martha I have found in the other Peterson branches, it is not unrealistic to think that Elisha might name a daughter after a departed sister.

Narration

There is also evidence that the Petersons were prominent members of the African American community in rural Newtown.

Scott Warnasch

So, if John Peterson was Martha Peterson’s father it is really interesting because John Peterson was the president of the United African Society who purchased the property of the cemetery.

Narration

It’s another connection between the possible identity of the remains and the location where they were found.

Scott Warnasch

Another interesting fact from the census is that Martha could read and write; we know this because there are boxes next to her name that shows she knows how to read and write.

Prof. Clarence Taylor

African Americans craved education, they wanted to learn how to read and write and they would go to great lengths including hiring teachers.

Prof. Carla Peterson

Literacy in many ways simply represents freedom.

Black leaders really see education as a path to emancipation.

And the one example that sticks out in my mind has to do with James Pennington

Prof. Clarence Taylor

James Pennington was an African American slave and he was born in 1807 in Eastern Maryland.

Prof. Carla Peterson

He escapes from slavery in Maryland and ends up in Newtown in Queens.

Prof. Clarence Taylor

Pennington became one of the leading abolitionists in the United States. He spoke against slavery. He travelled overseas and speaking before religious congregations against the system of slavery.

He eventually writes his autobiography that describes his conditions, his life, his experiences under slavery and how he escaped.

Prof. Carla Peterson

He was a blacksmith by trade so when he published a slave narrative it’s titled The Fugitive Blacksmith.

Scott Warnasch

James Pennington eventually by the early 1830s became the first black school teacher of the first black school in Newtown, around the same time that Martha would have been school age, somewhere around 8 or 9 or 10 years old.

It is amazing that Martha may have been taught by James Pennington; this amazing abolitionist and voice of the early black movement of abolition.

Narration

Using the 1850 census, Scott has been able to find a likely name for the woman in the iron coffin.

But is it also possible to find out what she might have looked like?

Scott Warnasch

Giving this woman a face is a little more challenging than some other situations because of the damage that she received from the machinery when she was discovered.

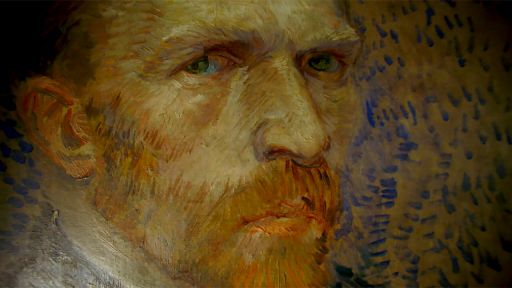

I have asked the forensic artist Joe Mullins to do a facial reconstruction.

Prof. Joe Mullins

I’m a forensic imaging specialist; a forensic artist.

My duties entail anything to assist law enforcement with identifying the deceased, finding the missing.

So, what we want to start with doing a facial reconstruction in this software is a pristine - you know - CT scan of the skull.

The skull tells you everything you need to know about what the face looked like in life. Everything from the projection of the nose, to the width of the nose, to the corners of your mouth, to your eyebrow.

Seeing all that information in, its makes it very easy to find the right puzzle piece to fit on this face to get the best representation of how she looked in life.

Step one is to repair the damage to the skull, so that means there’s damage to the lower mandible and the mouth is open a little bit.

So, we’re going to kind of mirror this image over here, flip it and – you know – close the mouth.

The details of the face are all here, it’s all mapped out, it’s just a matter of reading the map and applying those features on the right spot.

Applying the right facial muscles is also crucial in identifying - you know – how much tissue is there. We have landmarks on the skull because the muscles attach on the same place on everybody’s skull, regardless of your age or ancestry.

So, it’s important as you’re building up these features you’re finding the nose, the ears, the lips, you want to have a kind of structure to place it in. So, coming up with that grid, now the grid is essentially just an outline to tell us where those features are going to go.

So now we are going to start blocking in some features.

Narration

Joe selects age- and ancestry-appropriate features from a database of thousands of body parts.

Prof. Joe Mullins

Coming up with the nose… this is the nose that fits this skull.

She was well preserved within the iron coffin so we could see the hairlines, we knew it was parted in the centre and braided so that takes the guesswork out of it, which is great for a forensic artist having that information in front of us.

It’s like a digital puzzle that we are piecing together.

The last step is to modify these, finding the right skin tone and then corresponding that to all the pieces, so making it a uniform skin tone, and make sure it’s age appropriate.

I’ve stared at this face, after we complete, i’ve stared at it probably a hundred times since we’ve completed it because I am just fascinated.

It’s not just a pile of remains, or a body that was found in an iron coffin anymore.

A person is staring back at me. I have a photograph of a person who died that i’ve… i’ve brought her back to life.

Scott Warnasch

It is really interesting to have Joe reconstruct this woman’s face, so we can finally see what she looks like after 150 years.

But what I really want to do is offer some history back to the community that is directly related to this woman.

Scott Warnasch

Hi ladies

Historical Committee

Hello

Scott Warnasch

Thanks for coming out today for this wonderful revelation of the iron coffin lady. As you remember, the iron coffin lady suffered some damage from the machinery when she was discovered.

So, we were able to find a forensic artist to do a reconstruction of what the woman may have looked like, and I’d like to present that to you today.

Historical Committee

Oh wow!

Nice!

She’s very pretty!

She’s real!

Very good.

She looks like, um, Taylor. She looks like Taylor, our little Taylor.

Isn’t she beautiful?

Beautiful.

She’s very beautiful.

She looks like us.

We have a face now. And we can truthfully say that she looks as if she’s part of us. I would say. There’s no doubt; she’s a part of our community.

I really feel connected; I feel like I know that she’s family. It’s just returning to what is ours. And she’s ours.

It’s the past colliding with the future and we’re able to see this.

She became a prompt for us to reveal our history. Besides being a person, who is a part of our congregation, besides being a historical artifact, as a mummy, the iron coffin lady was also a prompt for St Mark to – as Judy said – think about our history.

Dr. Jeffrey Kroessler

Once you start asking questions about the people in the past, you can understand a way of life and that cannot but rebound to helping you understand your own life.

Prof. Clarence Taylor

Those folks at the bottom also shape history. It is not just the history of prominent people who leave their letters, who leave their memoirs, who have power, who shape the sort of narrative.

Some people call this bottom up history.

Prof. Carla Peterson

It is important for us to tell this story moving forward.

Generally, people have reduced African American history to a very low common denominator. If you said African or black American in 19th century, everybody would say ‘slaves’.

It is really important that we create this rich and diverse tapestry of African American life in the 19th century,

So, I think seeing this history is very important for blacks today to understand and recognise as part of their history and not just that ‘oh we were once slaves in the South’.

Rev. Kimberly L. Detherage Esq.

The discovery of the Iron Coffin Lady was actually no accident. You know that God allowed her to be discovered at such a time as this. That the community, that is changing, might be able to learn and understand more about the African American community, and the work and the contributions that African Americans have made to New York City and Queens.

Our history has been erased, so we don’t get to see this. We don’t get to see real photos. We may see a Harriet Tubman or Sojourner Truth, but we don’t get to see a woman, just an ordinary, everyday woman who lived life in New York day by day.

But we can identify with her because she does look like us. And so, it does make it personal.

Her life is a testament to our life.