Seeds of Peace Amidst Conflict: 1973 – 1993:

By the late 1970s, two of the opponents in the Arab-Israeli struggle were prepared to seek a peaceful resolution. U.S. “shuttle diplomacy” at the close of the October 1973 War had opened the way for further U.S.-brokered negotiations toward peace between Egypt and Israel. These were advanced with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s historic trip to address the Israeli Parliament in 1977. The Camp David Accords in 1978 established a framework for a broader Mideast peace, which — though never implemented — suggested elements and principles that would arise in later negotiations, such as autonomy for Palestinians. And the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, signed by Sadat and Menachem Begin in 1979, laid the plans for Israel’s return of the entire Sinai Peninsula in 1982. Egypt became the first Arab nation to recognize the state of Israel and forge a lasting peace. Yet this came at great cost; Sadat was viewed as a traitor by much of the Arab world, and in 1981 he was assassinated by Islamist elements of his own army.

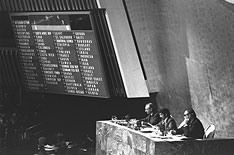

Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) had become an umbrella group of militant organizations, based first in Jordan, and later in Lebanon. Elements within the PLO, including Chairman Yasser Arafat’s Fatah organization, led terror attacks against targets in Israel and abroad. Among the most internationally visible of these were the murders of 11 Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in 1972, and the massacre at an Israeli school in Maalot that led to the deaths of 26 Israelis, most of them children. Over time, the PLO’s search for international recognition led to Arafat’s first appearance at the United Nations in 1974, where he appealed for peace while at the same time denouncing Zionism and affirming the armed pursuit to “liberate all of Palestine.”

By the late 1970s, for the first time in the nation’s history, rightist politicians in Israel’s Likud party assumed control of the Israeli government. Menachem Begin and others in this camp sought Israeli control of much of British Palestine and encouraged Jewish settlement in land beyond Israel’s 1967 borders. Meanwhile, southern Lebanon had become a base for PLO attacks. In response, Israeli forces led by Ariel Sharon invaded in 1982 and succeeded in expelling the PLO, which moved to Tunisia. But Israel, and Sharon specifically, became associated with one of the worst atrocities in recent Mideast history when a Christian Phalangist militia allied with Israel killed hundreds of Palestinians at the Sabra and Shatilla refugee camps in Lebanon. Sharon eventually resigned his post as defense minister and Israel slowly withdrew from Lebanon, leaving in its wake one of the most extreme anti-Israeli terror groups, Hezbollah.

Having achieved peace with Egypt and driven the PLO to Tunis, Israel experienced years of relative peace with many of its neighbors. However, resentment among Palestinians within the Occupied Territories still simmered as it became clearer that the PLO, Egypt, and Jordan were unlikely to bring them independence, as unemployment rose under the Israeli occupation, and as Jewish settlement increased. In 1987, an intifada, or “uprising,” began in Gaza and soon spread to the West Bank. The intifada combined protest and civil disobedience with rioting and violence — most often stone throwing, but also including the use of makeshift and military weaponry. Over the next six years, clashes between Palestinians and more heavily armed Israeli Defense Forces resulted in more than 1,000 Palestinian deaths, captured international media attention, and caused polarization in Israeli politics.

arly in the intifada, the PLO and Palestinian diaspora had grown increasingly concerned about their waning influence over the Occupied Territories. The Palestinian National Council — the multi-national group that had established the PLO — convened in 1988 to unilaterally declare an independent Palestinian state, renounce terrorism, and call for Israeli withdrawal from the Occupied Territories. As the intifada wore on, changes abroad created additional opportunities for peace. Arafat’s support for Iraq in the first Gulf War alienated wealthy supporters in the Gulf, while the U.S. victory allowed it to seek a broader Mideast peace. A dialogue began in 1991 in Madrid, leading to U.S.-sponsored talks in Washington. These expanded with the return to power of the left wing in Israel the following year, and eventually led to the Oslo peace talks facilitated by Norway.

The Oslo negotiations established a framework for a broader peace in 1993, with the Declaration of Principles. The two sides recognized each other’s right to exist — while making no statements regarding a Palestinian state — and Israel agreed to some troop withdrawal, primarily from the Gaza Strip. Though the agreement was heralded as a breakthrough by many and garnered the Nobel Peace Prize for Arafat, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, it left much disappointment. Many on the pro-Palestinian side protested that a politically and financially weakened Arafat had negotiated poorly, achieving no end to Israeli settlement while consigning the Palestinians to live in artificially “autonomous” regions. Some Zionist critics, for their part, claimed that Israel had given away territory that rightly belonged to Israel, and was essential for security, in exchange for promises that Palestinians would not keep.

Top photo: UN/DPI/T. Chen

- Previous: 1949 – 1973

- Next: 1993 – 2004