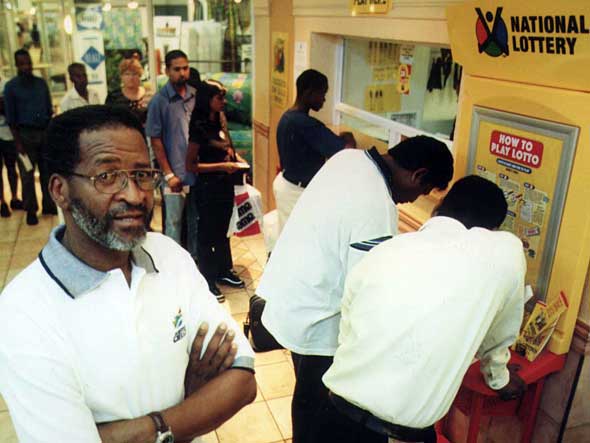

Uthingo, a black-led consortium, won the license to run the lottery because of its black empowerment model. |

By Nicole Itano

More than nine years after the end of apartheid, South Africa has emerged as Africa’s political superpower. The status is grounded in South Africa’s economic success. From cell phones and banks to fast food chains and grocery stores, if a new business opens in an African town, it’s most likely South African.

It wasn’t always the case. During the 46-year apartheid era, international sanctions put South Africa in economic isolation and on a slide toward bankruptcy. Relations with neighbors like Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Lesotho were more often hostile than not.

When the African National Congress came to power in 1994, the goal was to reverse that past. Unlike their white predecessors, Pretoria’s new black leaders saw South Africa as an intrinsic part of the rest of Africa. Borders were opened, trade barriers dismantled, and calls for integrating Africa’s economic and political systems rang out. It was a perfect scenario for a country with South Africa’s sophisticated infrastructure and advanced manufacturing capabilities. Since 1991, South African firms have invested an average of $1.3 billion per year in other African countries. Exports to African markets have soared by 59 percent in the last three years. The country is now Africa’s leading provider of foreign direct investment, according to the research group Liquid Africa.

At least on the surface, it’s a win-win situation. Less prosperous African countries get jobs, economic growth, and new technology, like cell phones that help them build modern economies. South African companies get much-needed new markets for industries competing in a global economy and, at a profit. South African companies say investing in Africa makes sense: it’s geographically close, familiar, and the markets are often wide open. There are also tax and exchange incentives provided by the South African government aimed at keeping investment money on the continent.

“Eventually the market in South Africa will reach some maturity,” says Monika Steinlechner, general manager of corporate finance for the MTN group, one of South Africa’s three cellular networks, explaining why her company has reached out into the continent. “But mobile technology, mobile phones, will actually be the means of communication in lots of less developed African countries. So the potential is huge.”

South Africa: Superpower on the Horizon?

But some critics charge that South Africa is becoming the “America of Africa.” No compliment intended.

Under President Thabo Mbeki, South Africa has become the leading force behind a pan-African movement meant to end conflict on the continent and stimulate much-needed economic growth. Mbeki’s New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) proposes having African countries review each other’s political and economic policies. If greater guarantees of peace and security are in place, the thinking goes, Western countries will increase investment. Eventually, Mbeki would like to see Africa become one giant economic community, similar to the European Union.

Critics charge, though, that NEPAD — plus two South Africa-dominated organizations, the African Union and the Southern African Development Community — could be used by the country to impose its political will on others. With a Gross Domestic Product of $412 billion, one of the world’s largest stock markets, and a sophisticated infrastructure and manufacturing base, South Africa, they observe, looks more like a charging elephant than a sympathetic mentor.

But the role of mentor comes at a cost for this continental superpower, as well. With Africa’s largest economy, South Africa is often left footing the bill for the work of the multilateral organizations it supports. The country keeps two battalions of peacekeepers in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi, and is considering sending troops to the new UN mission in Liberia. The Burundi operation alone costs South Africa an estimated $100 million a year, which some critics say could be put to better use addressing domestic ills like crime, poverty, and illegal immigration.

Some also fear that, by acting as the continent’s policeman, South Africa risks neglecting its own security needs.”The fact is that the South African National Defense Force is already overextended with its current deployments,” said Roy Jankielsohn, a spokesman for the opposition Democratic Alliance. “We cannot afford to commit further troops to foreign peacekeeping missions without seriously diminishing our domestic capacity, both in terms of border deployments and police support activities.”

In recent years, South Africa’s economic dominance has also brought hundreds of thousands of migrants flooding across South Africa’s borders, exacerbating already high unemployment and leading to rising xenophobia. And South Africa’s close ties with its neighbors always help investor confidence — financial observers say fears of a spillover from recent instability in Zimbabwe contributed to a 42 percent depreciation in South Africa’s currency, the rand, in the second half of 2001.

For now, Mbeki maintains that the benefits of South Africa’s new role outweigh the costs. “Individual national interests,” he told African leaders at the July 2003 African Union summit in Mozambique, must be kept “within the context of our continental and collective interests.” As the dominant player in African politics and economics, South Africa considers its own national interests to be inextricably tied to those of the continent. Whether or not this bet pays off is South Africa’s ultimate question.

Nicole Itano is a freelance reporter based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is a frequent contributor to the Christian Science Monitor.

Fast Facts:

| 1910 | Colonies decide — with British encouragement — on the formation of the Union of South Africa. |

| 1948 | National Party (NP) takes power and implements system of apartheid. |

| 1960s | International community begins to pressure South Africa’s government by imposing sanctions and excluding them from the Olympic Games. |

| 1991 | President de Klerk lifts most apartheid laws, including the Population Registration Act, and frees Nelson Mandela. |

| 1993 | Most remaining UN sanctions on South Africa are lifted, along with most of those imposed by the U.S. and by many African nations. |

| 1994 | First non-racial elections. Twenty-two million people turn out to vote, electing the African National Congress (ANC) and Mandela into power. |

| 1998 | A series of black economic empowerment laws are passed, including the Employment Equity Act. |