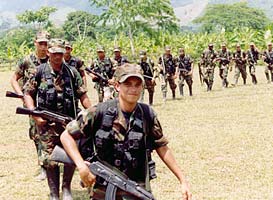

Although the AUC (Autodefensas Unidas De Colombia / United Self-Defense Units of Colombia) formed as an umbrella group of paramilitary organizations in the late 1990s, its component groups trace back at least a half century. In the 1950s, wealthy rural elites hired militias to defend their properties and businesses from a variety of threats, including armed left-wing guerilla groups. In 1968, local self-defense groups were permitted by legislation, and for decades, these militias filled a power vacuum left by sparse policing in many of Colombia’s rural areas. In the 1980s, private militias grew immensely with support from drug cartels that employed them to defend their coca plantations. And in the 1990s, new leadership began to transform them into a more unified military and political force.

Although the AUC (Autodefensas Unidas De Colombia / United Self-Defense Units of Colombia) formed as an umbrella group of paramilitary organizations in the late 1990s, its component groups trace back at least a half century. In the 1950s, wealthy rural elites hired militias to defend their properties and businesses from a variety of threats, including armed left-wing guerilla groups. In 1968, local self-defense groups were permitted by legislation, and for decades, these militias filled a power vacuum left by sparse policing in many of Colombia’s rural areas. In the 1980s, private militias grew immensely with support from drug cartels that employed them to defend their coca plantations. And in the 1990s, new leadership began to transform them into a more unified military and political force.

A key component of the AUC is the northern paramilitary group ACCU, or Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba y Urubá / Peasant Self-Defense Groups of Córdoba and Urubá. This unit was founded by Fidel and Carlos Castaño to avenge the murder of their father by FARC guerillas. However, it also provided security for coca plantations and drug trafficking rings in northern rural areas. Another powerful paramilitary organization operating in urban areas was MAS (Muerte a Secuestradores / Death to Kidnappers), created in the early 1980s in response to the kidnapping of a member of the family that headed the Medellín cartel.

The Paras and the State

For decades, Colombia’s paramilitary organizations have maintained a close and cooperative relationship with many parts of the Colombian state. There are, in the broadest sense, parallel interests between the two groups, in that both oppose an overthrow of the government by leftist insurgent groups, and both are, to a substantial extent, working on behalf of the country’s wealthier communities. However, the cooperation between these groups is, in many cases, quite specific and is an important component of the civil war.

The relationship between the state and the paramilitaries is perhaps most evident in the flow of personnel from the Colombian military and police to the paramilitaries. Reports are that on the order of 1,000 former members of these government security forces have joined the AUC, many of them after being ousted from their official positions for human rights abuses.

This flow also builds channels of communication between the government and paramilitaries, providing the latter with access to government information and intelligence. Many claim that this communication gives the two groups the ability to coordinate their efforts in such a way that the government benefits from, but avoids conducting much of the “dirty work” of murder and human rights abuses that are carried out by paramilitaries.

These urban and rural militias opposed and threatened not only rural guerrilla groups themselves, but also leftists generally and their supporters — or suspected supporters — including politicians, union leaders, religious figures, and other civilians. For many years, it has been reported by journalists and human rights groups that paramilitaries have been responsible for killing, terrorizing, and forcing the displacement of civilians — mostly farmers and villagers. It is estimated that some two to three million Colombians, or roughly five to seven percent of the country’s population, is displaced in some fashion by the conflict. While the AUC claims that it targets only guerillas, critics argue that a parallel purpose of the paramilitary activities is to drive peasants from land that then passes to the AUC’s patrons, large landowners, business people, and narco-traffickers.

In the mid-1990s, when his brother disappeared under mysterious circumstances, Carlos Castaño inherited the helm of the ACCU and moved to consolidate authority over all of the country’s right-wing paramilitary groups. In 1997, he announced the creation of the AUC alliance. Castaño claimed that, although the AUC does receive some income from the drug trade, its primary purpose is to rid the country of left-wing “subversives.” In 2001, as part of a broader campaign to promote the AUC as a political party, Castaño named himself the organization’s political head and passed the military leadership title to others. However, the group’s continuing connections with drug cartels and its record on human rights led the U.S. State Department to both list the group as a terrorist organization and seek Castaño’s extradition on drug trafficking charges.

Under Castaño’s leadership, the AUC saw an increase in recruits — it became the fastest growing armed group in the country and now numbers more than 15,000 — as well as increased territory and political influence. Following an April 2004 shootout, however, Castaño dropped out of sight, and has not been heard from since June, when the AUC announced that he had resigned his senior position. The nature of the handover is unclear — some reports indicate that Castaño may have been killed, while the AUC maintains officially that he has simply relinquished day-to-day operational control and continues to advise the group. Whatever the reality of the situation, control of the group passed to a nine-member council, headed by Salvatore Mancuso, who has emerged as the AUC’s most visible spokesperson.

Many Colombians approved of Castaño’s hard-line approach to combating insurgents and criminals. However, the paramilitaries’ successes have also brought harsh reprisals, such as the massacre, by the FARC, of 34 coca farmers employed by paramilitaries in June 2004, the worst mass killing since Uribe took office. This may signal the initiation of a counteroffensive by the FARC to reclaim territory lost to the paramilitaries recently.

Under Mancuso, the paramilitaries began disarmament talks with the government, signing a cease-fire agreement in December 2002. Still, the AUC did not abandoned key drug-producing regions, like the places along the Venezuelan border where FARC massacre took place in 2004. As of summer 2005 Uribe’s government still hopes to persuade paramilitary leaders to order that their remaining troops demobilize by the end of 2005. However, Uribe continues to endure harsh criticism from global organizations like Human Rights Watch, who claim in a recent report that the peace talks “will almost certainly fail to dismantle these groups and result in a lasting peace”.

Aside from Uribe’s claims that his main priority upon taking office in 2002 would be to bring down the leftist insurgents, he has, in fact, made substantial progress toward bringing peace with paramilitaries. However, many regret that the government’s olive branch has come in the form of what some call a hasty pardon for war criminals. In July 2005, Uribe signed into law the controversial Peace and Justice Law, which gives concessions, partial amnesty, and other benefits to paramilitary fighters if they disarm. The law allows for the demobilization of up to 20,000 paramilitary fighters but also shields paramilitaries from serious punishment and protects them from extradition to the United States, where they are wanted for their role in Colombia-U.S. drug smuggling. The legislation is backed by the Bush administration and the U.S. ambassador to Colombia, William Wood.

Despite the U.S. president’s support of the law, however, critics of the legislation include the United Nations, international human rights advocates, and prominent U.S. senators such as Richard Lugar and Patrick Leahy. These detractors say that the law’s protection of paramilitary fighters from extradition – and its promise of minimal prison sentences for offenses such as drug trafficking and murder – undercut the goals of demobilization. On July 7, U.S. Senate Appropriations Committee threatened to block as much as $3 million in aid to the demobilization process unless the law was changed to allow for the complete dismantling and extradition of paramilitary groups to the U.S. on drug trafficking charges. The threat did not dissuade Uribe from signing the law. And the committee’s decision is pending before the Senate. AUC leader and cocaine trafficker Salvatore Mancuso is one of the men who benefits the most from the recently passed law, as he has become untouchable, despite his placement on the U.S.’s list of 18 commanders wanted for extradition.

- Previous: FARC Guerillas

- Next: Roots of Conflict