By Tamara Makarenko

August 22, 2002

As the U.S. military build-up continues in Central Asia, one frequently overlooked factor in the region’s stability demands attention. It is the link between Afghan opiates and terrorism.

After September 11, Western government officials and media reports put the onus for this link on al-Qaeda and the Taliban. But neither of these groups was ever interested in the large-scale production or trafficking of opiates.

The alliance between narcotics and terror is spearheaded by a terrorist group little known to most Westerners, but one, which, with an estimated 70 percent of Central Asia’s drug trade under its control, according to Interpol, is the true wildcard for stability in the region. Its name is the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU).

Founded in 1998 by underground mullah Tohir Yuldashev and Afghan War vet Juma Namangani, the IMU declares as its goal the overthrow of the repressive regime of Uzbekistan’s President Islam Karimov — one with a long track record of persecuting practicing Uzbek Muslims — and the establishment of an Islamic state. The group fought with the Taliban and al-Qaeda against U.S. forces during the war in Afghanistan and is believed to have received funding both from Osama bin Laden and Saudi sources. It has operated out of bases in both Tajikistan — where Namangani fought with Islamic militants during that country’s 1992-1997 civil war — and, of late, Afghanistan.

The Fergana Valley, where Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan converge, is the focus point for most of the IMU’s attacks and a key recruiting ground for the group’s roughly 1,000 militants. This is Central Asia’s spiritual homeland and the location of 20 percent of its population. Before September 11, the IMU’s incursions here were largely focused on government forces near its drug trafficking routes. The goal was to deflect attention from important shipments of Afghan opiates or from reconnaissance of new routes.

Now, with the political stakes in Central Asia at an all-time high, the IMU appears to be planning to diversify its attacks away from its usual incursions on border installations. European and Central Asian intelligence reports suggest that the group is now planning attacks on U.S. military installations in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and elsewhere in the region as well as assaults on various local governments.

But unlike al-Qaeda and the Taliban, the IMU is not tightly wedded to Islamic doctrine. Though the group acted as a cell for al-Qaeda in the global jihad against U.S. interests, the IMU’s military commander, Juma Namangani, was known more as a guerilla leader. Needing money for arms and supplies and to pay fighters, Namangani turned to drugs.

By the late 1990s, Namangani was using the IMU’s network of activists to traffic heroin and other opiates from Afghanistan through Central Asia and on to Europe. The group’s success in drug trafficking is due to their knowledge of mountain routes; their ability to corrupt border officials; and, more importantly, their willingness to enter into armed engagements with border guards to distract attention from trafficking operations in nearby areas.

After the U.S. bombardment of Taliban strongholds in northern Afghanistan, unconfirmed reports circulated that Namangani had been killed and that, under the leadership of Uzbek mullah Tohir Yuldashev, the IMU was now putting ideology and radical Islamic ideals first. Even so, with financial and logistical support from the Taliban and al-Qaeda no longer reliable, the IMU has little reason to abandon its near monopoly on Central Asia’s drug trafficking business.

Financing the new campaign will be opium. But so far, the U.S., along with the rest of the international counter-terrorism coalition, has shown little resolve in combating drug trafficking as a financial resource for this terrorist group.

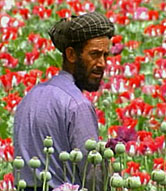

During the bombardment of Afghanistan, known drug stockpiles and laboratories maintained by the IMU and other criminal groups were not destroyed. Instead, the international community has supported relatively weak attempts by Afghanistan’s interim government to entice farmers to destroy their opium poppy crops in exchange for $700 per acre of land. Compared with the $3,500 that farmers normally collect for the same amount of cultivated opium poppy, it is doubtful that this policy alone can address Central Asia’s soaring heroin trade.

Meanwhile, a foundation is being laid that will only make the IMU’s terror tactics that much easier to accomplish. As trafficking in opium and opium derivatives has increased, so has corruption among government officials, drug addiction, crime and rates of HIV infection. Democratization efforts have faltered. Violent border clashes sparked by IMU attacks have led Central Asian countries to concentrate on accusing one another of security failures rather than on rooting out this common problem.

There are practical measures that should be taken — training border guards, providing screening technology — but equally important is the need to promote human rights and human development throughout Central Asia. Without that commitment, Washington’s much ballyhooed support for Central Asia may soon come to naught.

Tamara Makarenko is a U.K.-based analyst who investigates and writes on the nexus between organized crime and terrorism. She is a consulting editor for JANE’S INTELLIGENCE REVIEW and a senior associate with Cornell Caspian Consulting, a Swedish strategy firm focused on the Caucasus and Central and Southwest Asia.