Fishing For Answers: Making Sense of the Global Fish Crisis

Reprinted from a 2004 report by the World Resources Institute

For millennia, harvesting resources from the seas, lakes, and rivers has been a source of sustenance and livelihood, and a mainstay of local culture. Today, fishing remains key to food security for millions of people, a bulwark of local employment, and a significant factor in the global economy. In fact, about 1 billion people — largely in developing countries — rely on fish as their primary animal protein source and an estimated 35 million people are directly engaged, either full- or part-time, in fishing and aquaculture. In terms of income generation, fisheries are extremely important as well, generating over US$55 billion in international trade anually.

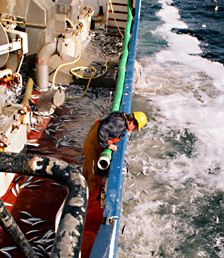

Yet, the nature of the fishing enterprise and the condition of the marine and freshwater resources it relies on has changed radically over the last 100 years. During that time, the increase in the world’s population and the need for economic development has brought a rapid expansion of commercial fishing and an overwhelming upsurge in our capacity to exploit fish stocks. In the last half century, a tide of new technology — from diesel engines to driftnets — has swept aside the limits that once kept fishing a mostly coastal and local affair. The result has been a rapid depletion of key stocks, and serious disruption and degradation of the marine and freshwater ecosystems they live in — what many have termed a “global fisheries crisis.”

Since 1992, overfishing — the action of fishing beyond the level at which fish stocks can replenish through natural reproduction — has become one of the major natural resource concerns in the industrialized world, and increasingly in developing nations as well. Seventy-five percent of commercially important marine, and most inland water fish stocks are either currently overfished, or are being fished at their biological limit, putting them at risk if fishing pressure increases or the habitat degrades.

It was once thought that commercial fish species that were widely distributed and abundant were unlikely to be threatened with biological extinction even if heavily fished. But in recent years it has become clear that this is not the case. A small number of commercial fish species have now joined endangered whales and sea turtles on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. Scientists warn that when fish populations become severely depressed, a threshold can be breached making recovery questionable even if fishing effort is reduced or stopped. In May 2003, Canadian biologists declared the Atlantic cod an endangered species after concluding that some stocks face imminent extinction — this in spite of the fact that the Canadian cod fishery is closed.

Despite troubling statistics, most people have little idea of what the “fisheries crisis” is, or what it means to them. From a consumer’s point of view — at least in most developed nations — the sad condition of fish stocks is not obvious. There are still plenty of fish available in markets and restaurants, although the types may have changed and the prices may be higher. Unfortunately, pressure on fish stocks is primed to increase even as stock conditions continue to worsen. Demand for seafood products has doubled over the last 30 years and is projected to continue growing at 1.5 percent per year through 2020 as global population grows and per capita fish consumption rises. The number of fishermen and fish farmers is growing markedly as well, having doubled in the last 20 years with most of the increase occurring in developing countries as people turned to fishing for an alternative or supplemental source of income.

As ocean catches have dwindled, aquaculture — the practice of farm-raising fish and shellfish — has burgeoned and diversified to take up the slack to meet food and income needs in developing and developed countries. In fact, over the past three decades, aquaculture has become the fastest growing food production sector in the world, accounting for 37.9 million metric tons of fishery products in 2001 — nearly 40 percent of the world’s total food fish supply. But the heavy dependence of intensive systems on human inputs — water, energy, chemicals — and on wild fish for feed and seed, as well as the effects on ecosystems and species are major constraints to the sustainability and future growth of this industry.

Achieving sustainable fishing practices and maintaining healthy fish stocks will not be easy. It will require action at many levels: changes in national economic development plans and structural government reforms; changes in how fishing rights are allocated to both small-scale fishers and industrial fleets; changes in international cooperation and international trade negotiations; and better compliance with international norms. It will also require a more concerted effort by nations to address the management and monitoring of small-scale and inland fisheries sectors, which are largely unregulated and ignored today.

The fishing sector is far too important to allow its continued downward spiral through inaction, particularly when some initial steps toward sustainability are possible today. There is no question that the world’s fisheries can be managed to produce a significant harvest of fish without depletion. But how large this harvest can be, and how fishing operations must be managed to produce this harvest sustainably is still a topic of much debate and experimentation in most parts of the world. There is no “one-size-fits-all” management approach suitable to all nations and fish stocks. However, there are a variety of strategies that, when combined, can clearly contribute to more sustainable fishing practices. These include such steps as:

The fishing sector is far too important to allow its continued downward spiral through inaction, particularly when some initial steps toward sustainability are possible today. There is no question that the world’s fisheries can be managed to produce a significant harvest of fish without depletion. But how large this harvest can be, and how fishing operations must be managed to produce this harvest sustainably is still a topic of much debate and experimentation in most parts of the world. There is no “one-size-fits-all” management approach suitable to all nations and fish stocks. However, there are a variety of strategies that, when combined, can clearly contribute to more sustainable fishing practices. These include such steps as:

- improving licensing and monitoring regimes;

- developing refined fishing gears that reduce damaging impacts and unintended catches;

- establishing marine protected areas that act as refuges for recovery of fish stocks;

- managing river basins as integrated units with water allocation schemes to sustain river flows and the natural ecosystem functions and processes;

- supporting better stock assessments that yield more accurate catch quotas;

- pursuing stricter enforcement of fishing regulations and tighter international cooperation to improve compliance with international fishing treaties;

- establishing new institutional arrangements that can adopt an integrated or ecosystem approach to resource management;

- creating national policies that incorporate fisheries into development and poverty reduction strategies;

- putting in place economic policies that give fishers incentives to reduce fleet sizes and that reward responsible fishing practices;

- supporting and encouraging more sustainable aquaculture practices, and streamlining the monitoring and reporting of new farming methods in order to avoid negative impacts on wild stocks; and

- making fish consumers aware of the dimensions of the fisheries crisis and their part in it, and educating them on which seafood products are sustainably harvested and which should be avoided because of their high environmental impact.

The world’s fisheries suffer from severe overcapacity, with too many boats chasing fewer and fewer fish. At the same time, global demand for fish and fishery products is growing and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Industry, fishermen, aquaculturists, and consumers all need to participate in shaping the way we manage fisheries in the future.

This essay is an exerpt from the Executive Summary of FISHING FOR ANSWERS: MAKING SENSE OF THE GLOBAL FISH CRISIS, a report by the World Resources Institute.