Milosevic’s war crimes trial began in February 2002 and could last over a year. Learn about the trial, the charges against Milosevic, his co-accused and the tribunal.

CHAPTER 1

The Trial

Extradition

Former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic is the first head of state to stand trial for war crimes and genocide. The process that brought Milosevic to the UN-run International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague was fraught with turmoil. Belgrade police arrested Milosevic in April 2001 after a 36-hour armed stand-off and suicide threats by Milosevic. Courts in Yugoslavia had tried to prevent the former leader’s extradition to The Hague, but had been overruled by the country’s new, pro-reform government. Anxious to secure much-needed international aid money and mend relations with the West, Yugoslavia finally agreed to Milosevic’s arrest. His subsequent extradition two months later helped the wartorn country secure over $1 billion in aid from the U.S., World Bank, and the European Union.

Life in Jail

Milosevic is held at the tribunal’s jail in Scheveningen, a suburb of The Hague and just over a mile from the tribunal. The high-tech facility, equipped with a gym, a library and a room for religious devotions, is patrolled by UN guards. The former leader is free to mix with other defendants indicted for war crimes in Yugoslavia, whether Serbs, Croats or Muslims. All prisoners have their own cell, each with its own bathroom, radio and satellite television. Milosevic is allowed to telephone family for seven minutes a day. When family members — most frequently, his wife, Mira Markovic — visit there are special rooms where they can spend time together. For Milosevic’s 60th birthday in August 2001, Mira Markovic, their two-year-old grandson Marko, and daughter-in-law Milica Gajic made a special visit to The Hague. In Belgrade, Markovic and other Serbs can follow the trial on television through independent station B92, a strong critic of the Milosevic regime.

Milosevic’s Defense

Although Milosevic faces three indictments, he will stand trial only once. The trial began on February 12, 2002, but Milosevic has refused to accept the legitimacy of the tribunal because it was approved by the UN Security Council and not by all UN member countries. The tribunal entered a not-guilty plea for Milosevic when he refused to enter a plea himself.

Milosevic has also refused to appoint a defense counsel or talk to his ami curiae , so-called “friends of the court” who help ensure defendants receive fair trials. Since Milosevic is representing himself, without a defense counsel, the tribunal has allowed him to cross-examine witnesses.

In his opening statement to the court, presided over by Judge Richard May from the UK, Milosevic again challenged the tribunal’s legitimacy and accused NATO of war crimes. He later stated that he plans to call on former U.S. President Bill Clinton, former Secretary of State Madeline Albright and UN Secretary General Kofi Annan as witnesses to the Dayton peace process that ended the war in Bosnia. He may also call German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder and UK Prime Minister Tony Blair to testify on other indictments.

The Prosecution’s Case

Prosecutors will rely on the testimony of witnesses, political insiders, documentary evidence and communication intercepted in Kosovo by NATO. Since Milosevic signed few papers and gave many orders face-to-face, the testimonies of associates will be crucial to the prosecutors’ case. However, the prosecutors have had difficulty in persuading Serbian political figures to appear on the witness stand.

The prosecution is scheduled to finish its case in May 2003, but Milosevic’s health may cause additional delays. Since the trial began, Milosevic has had the flu twice. In July 2002, doctors found Milosevic to be at serious risk of a heart attack and ordered him to decrease his workload. This announcement caused analysts to speculate that Milosevic may die before the trial ends.

CHAPTER 2

While Milosevic was in power as President of Serbia and President of Yugoslavia, Yugoslavia was ripped apart by wars that resulted in the deaths of over 270,000 Croats, Bosnians, Serbs and Kosovars. By the time Milosevic was toppled by pro-democracy demonstrators in 2000, only Serbia and Montenegro remained part of Yugoslavia.

The UN war crimes tribunal issued three indictments against Milosevic in connection with the wars in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo. He is the first former head of state to be with charged with war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

Croatia Indictment

Date issued: October 8, 2001

The Croatia indictment alleges that during the period between 1991 and 1992, while Milosevic was president of the Republic of Serbia, he exercised control of the police and military that forcibly removed the majority of Croats from one-third of the Republic of Croatia in order to make the area part of a new, Serb-dominated state.

Charges

- 9 counts of grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 that governs war crimes

- 13 counts of violations of laws or customs of war

- 10 counts of crimes against humanity

Background

Croatia declared its independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, one year after electing nationalist Franco Tudjman as its president. This declaration set off fierce fighting between Croatian troops and Croatian Serbs, the ethnic minority in the country. By the end of 1991, Croatian Serb secessionists, along with Yugoslav army troops, had seized control of the Serb-dominated region of Krajina, about a third of Croatia.

In January 1992, after several failed cease-fires, United Nations peacekeepers entered Croatia to maintain an uneasy truce. But fighting never entirely stopped during the years UN peacekeepers were in Croatia. In July 1992, Serbs shelled the seaside town of Dubrovnik. In the summer of 1995, the Croatian army retook the Serbian-held territories — western Slavonia and Krajina — and expelled 150,000 to 200,000 Serbs. It was not until Tudjman signed the Dayton peace accords — which officially ended the Bosnian war — did peace spread to Croatia. About 20,000 people had been killed in the conflict and 400,000 people left homeless.

Bosnia – Herzegovina Indictment

Date issued: November 22, 2001

The Bosnia indictment is the only indictment that contains charges of genocide, the most serious of all the crimes under the tribunal’s jurisdiction. According to the indictment, Milosevic is responsible for the murders of thousands of Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats from Bosnia and Herzegovina between 1992 and 1995.

Charges

Two counts of genocide

Two counts of genocide

- 10 counts of crimes against humanity

- Eight counts of grave breaches of the Geneva Convention of 1949

- Nine counts of violations of laws or customs of war

Background

Several months after the start of the Croatian War, fighting began in Bosnia in 1992 between Bosnian Croats and Muslims against Serbs who had boycotted an earlier referendum calling for independence. Milosevic, under the guise of protecting Serbs in Bosnia, sent Yugoslav troops to support them in the conflict. Bosnian Serbs drove out Muslims from over half of Bosnia to create Serb-dominated areas. Croats and Muslims also engaged in ethnic cleansing and other human rights abuses.

In August 1994, Bosnian Croats and Muslims agreed to a peace plan known as the Dayton Peace Accords that split Bosnia with Bosnian Serbs. The Muslim-Croat alliance got 51 percent of Bosnia, while 49 percent went to Bosnian Serbs. But despite the peace plan, the Bosnian Serbs continued to carry out massacres against residents in Sarajevo and Srebenica — supposed UN “safe haven” cities for Muslims civilians. By the end of the war, about 250,000 people had died and 1.8 million became refugees.

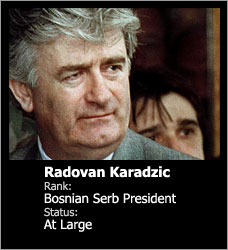

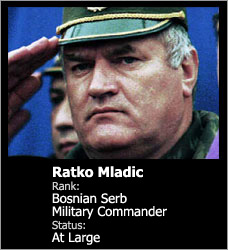

Other Defendants

Though he commands the lionshare of media attention, Milosevic is not the only former leader or official indicted by the UN tribunal for causing bloodshed in Yugoslavia. Read about Serbia’s most wanted men, Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, and about Milosevic’s co-accused in the Kosovo indictment.

Bosnian Serb President Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, his former military commander, were indicted on July 24, 1995 for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina and, specifically, in Srebrenica. According to the indictment, Karadzick and Mladic were ultimately responsible for atrocities conducted by the Bosnian Serb army, including internment of Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croat civilians in inhumane conditions where they were subject to abuse. In July 1995, approximately 7,000 Bosnian Muslims died when Bosnian Serb troops attacked the UN-protected town of Srebrenica. The attack ranked as the worst mass killing since World War II.

Milosevic’s four co-accused in the Kosovo indictment are charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity in the 1999 conflict with Kosovar Albanians. The group is charged with being criminally responsible for deporting over 800,000 ethnic Albanians. Many were killed, abused and had their possessions and identification papers stolen en route to neighboring countries, Albania and Italy. The tribunal charges Serb forces under the co-accused’s command with responsibility for massacres in a dozen towns in Kosovo including Racak, Mala Krusa and Dakovica.

Sainovic and Ojadnic surrendered voluntarily to the tribunal in April and May 2002 after the Yugoslavian government passed a law agreeing to hand over those already indicted. Sainov and Ojadnic are still in pretrial proceedings. Stojiljkovic shot himself in front of the parliament hours after its members voted to extradite war crimes suspects to The Hague. Milutinovic’s immunity is expected to run out with his presidential term in 2002.

Sainovic and Ojadnic surrendered voluntarily to the tribunal in April and May 2002 after the Yugoslavian government passed a law agreeing to hand over those already indicted. Sainov and Ojadnic are still in pretrial proceedings. Stojiljkovic shot himself in front of the parliament hours after its members voted to extradite war crimes suspects to The Hague. Milutinovic’s immunity is expected to run out with his presidential term in 2002.

Both Karadzic and Mladic remain at large. Karadzic is thought to be in eastern Bosnia, where he has been spotted surrounded by bodyguards. Mladic, who may be ill, is thought to be hiding in the mountains of Montenegro.

CHAPTER 4

The Tribunal

The trial of Slobodan Milosevic at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at The Hague is the first international war crimes trial since the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials after World War II. The ICTY along with the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was established by a resolution of the UN Security Council in 1993 and is funded by the UN General Assembly. Although thousands of soldiers were involved in atrocities, the court is charged with prosecuting only those ultimately responsible for having ordered those crimes.

What Are the Tribunal’s Powers?

The tribunal has jurisdiction over war crimes committed since 1991 in the territory of the former Yugoslavia. The tribunal can request national courts to discontinue their own proceedings in deference to the ICTY.

The tribunal has authority to prosecute actions in the following areas:

- Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949:

The Geneva Conventions defined certain acts as war crimes. Grave breaches are crimes such as murder, rape, torture or persecution on the basis of racial, political or religious grounds committed during hostilities as part of a systematic act directed against the civilian population. The United Nations General Assembly passed the Geneva Conventions in 1949.

- Violations of law and customs of war:

Rape, murder and other crimes committed against those who were not involved in military hostilities.

- Genocide:

Murder and other crimes committed with the intent to destroy a national, ethnic or religious group

- Crimes against humanity:

Murder and other crimes committed against civilian populations, before or during the war, on political, racial or religious grounds.

How Is the Tribunal Structured?

How Is the Tribunal Structured?

The Tribunal is made up of the Office of the Prosecutor, the Chambers and the Registry. The Office of the Prosecutor (OTP), which is independent of the UN Security Council and other organs of the ICTY, conducts investigations by collecting evidence and identifying witnesses. OTP officials are police officers, crime experts, and lawyers. Carla Del Ponte, a Swiss lawyer, is the Chief Prosecutor and is the third person to head the OTP. Canadian Louise Arbor and South African Richard Goldstone have served previously as heads of the OTP. Once the OTP issues indictments, it relies on the former Yugoslav republics or the international peacekeeping forces, S-For and K-For in Bosnia and Kosovo, to make arrests.

Since defendants cannot be tried in absentia, trial proceedings can only begin once the defendant is brought to The Hague. The case can be tried in one of the tribunal’s three trial chambers and decisions can be appealed in the appeals chamber. Each of the trial chambers has a panel of three judges and the appeals chamber has five judges. Judges are elected by the UN General Assembly for a period of four years after which they can be re-elected.

The Registry houses all the documents and evidence collected by the tribunal. It also manages the detention center where defendants are held following their arrests and during trials.

What Are the Possible Sentences?

Judges must determine that a defendant is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. It takes majority by the three-judge panel to convict a defendant. The maximum sentence is life imprisonment. Sentences will be served in one of the countries that have been approved by the Tribunal to house prisoners: Austria, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, Norway, Spain, and Sweden.