Clerics reading headlines while shopping for newspapers at a kiosk in Qom, Iran in July 2004 Photo: Afshin Marashi |

By the early nineteenth century Iranian reformers had become keenly sensitive to what they perceived as the relative weakness of their society in comparison to the growing threats from Imperial Russia to the north and the British Raj in the south. In order to transform Iranian society, reformers in the Qajar government sent students to Europe in order to study the new scientific and technological developments that were seen as the secrets of European strength.

Among the first of these students to travel abroad was Mirza Saleh Shirazi, who was sent to Britain in 1815. Shirazi’s stay in Britain impressed upon him the important role of newspapers in a modern society, and Shirazi brought back to Iran the technology to establish the first Persian-language newspaper. This first paper, the “Khaqaz-e Akhbar” (literally News-Paper), was short-lived, but was the first in a long series of periodicals designed to represent the government’s official point of view on matters of politics and policy. Its successor, the “Vaqaye’-e Ettefaqiyeh” (The Chronicle of Events), began publishing in 1851, and was much more successful in the long term as an official organ of the state.

At the same time that the state was working to establish an official press, dissident and radical groups in Iranian society were beginning to recognize the usefulness of the new technology of print to disseminate ideas and shape public opinion. Significantly, this early Persian-language radical press was almost invariably published outside of Iran. London, Calcutta, Cairo, Istanbul, and Baku, were all important cities with sizable communities of Iranian expatriates, and during the second half of the nineteenth century these expatriate communities became the home for an emerging radical Persian-language press. Newspapers such as “Akhtar” (the Star), published in Istanbul, “Hikmat” (Wisdom), published in Cairo, “Irshad” (Guidance), published in Baku, “Qanun” (Law), published in London, and “Habl al-Matin” (The Strong Bond), published in Calcutta became the instruments through which Iranians first challenged the authority of the monarchy, as well as forums for proposing dramatic social, cultural, and political changes for Iranian society.

It was through these newspapers that a new vocabulary entered into Iranian political language. Concepts and words such as liberalism, secularism, nationalism, and constitutionalism, all entered into Iranian political consciousness during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as Iranians read these publications — which were officially banned — in coffeehouses, mosques, bookstores, and bazaars. Only official and semiofficial papers were allowed to be distributed, and then only through the efforts of an underground network of smugglers and printers. This underground movement managed to defy the ban on the radical press by importing what texts they could and reprinting important works of criticism published abroad, thereby ensuring that radical journalism remained available in spite of government censorship.

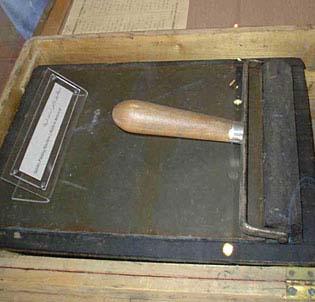

A hand press used during the Constitutional Revolution to print nightly broadsheets, currently on display at the Constitutional Revolution Museum in Tabriz, Iran Photo: Afshin Marashi |

The government’s fears were not unfounded: the writings of the dissenting expatriate community did have an impact on Iranian politics, and by the beginning of the twentieth century the coffeehouse discussions and reading groups had become full-fledged revolutionary societies. Growing radical sentiment led to a period of political upheaval, and eventually to the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1911, which forced the government into establishing a representative assembly (the Majles) and adopting a written constitution.

Revolutionary sentiment was not solely the creation of the progressive, Western-influenced underground press. Foreshadowing the coalition of disparate parties who would participate in the 1979 revolution, secular progressives, radicals, financial and political powerbrokers and the Islamic “ulama” (clergy) collaborated against the Qajar shah. These groups found their own way around the publications ban: the clerics preached an antigovernment message, reaching an audience that had no access to the underground press or contraband smuggled papers, while the revolutionary societies clandestinely distributed antigovernment pamphlets, the “shabnamehs” or night letters.

Together, these groups were able to reach a constituency broad enough to pressure the government into adopting the proposed assembly. The hoped-for period of parliamentary rule, however, never arrived, collapsing under British and Russian pressure, reconsolidation by the Qajar dynasty, and the arrival of the First World War. The constitutional movement did lead to a period of press freedom: the ban on nonofficial periodicals was lifted, and an explosion of publishing — with the new papers willing and able to present political commentary — followed the establishment of the first Majles.

The Constitutional Revolution was in many ways the political expression of Iran’s debate, begun in the first half of the nineteenth century, on how to reform itself. That debate had led to the importation of the technology of the modern press in the first place, and the radical press that emerged played a crucial role first in establishing the direction of that evolving debate, and eventually in determining the outcome of Iran’s first twentieth-century revolution. Ideas first voiced in banned newspapers in the late nineteenth century became the basis for a popular movement that demanded a new legal and constitutional framework meant to limit the authority of the Iranian monarchy.

- Previous: Introduction

- Next: Under the Pahlavis