India’s Enduring Hindu-Muslim Contest:

500 BC – 550 AD: Kingdoms and Empires

Indian history stretches back 4,500 years to the Indus Valley civilization centered on the banks of the Indus River in northern India. Hindu culture began around 1500 BC, with the arrival of the Aryans, Central Asian nomads whose pantheon, caste system, and sacred “Vedas” — oral hymns, worship manuals and philosophies — are strongly reflected in today’s Hindu religion.

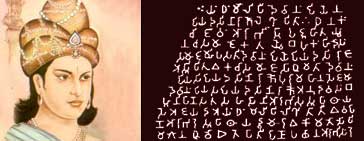

By the 6th century BC, the Kingdom of Magadha, strategically situated along Ganges trade routes, had extended into central and eastern India. Within a century, large kingdoms based on Vedic culture had begun to form throughout northern India. In 321 BC, just after Alexander the Great’s invasion of India, Magadha was seized by Chandragupta Maurya, who expanded it into what would become the first great Hindu empire, the Mauryan Empire. Under Chandragupta’s grandson Asoka, the Mauryan Empire reached its territorial limit, before breaking up into smaller states. More than half a millennium later, another Chandragupta once again succeeded in unifying most of India. Deemed the Hindu Golden Age, the resulting Gupta Empire (AD 320-550) led to a flowering of literature, science and technology. But as with its Mauryan predecessor, the Gupta Empire’s fall ushered in an era of warring states.

900 – 1707: Muslim Conquest

Islam came to India in the 10th century when the Ghaznavids, a Turkic tribe, annexed the area now known as Punjab. By 1200, Muslim warlords had conquered much of northern India, and by 1206 had founded the Delhi Sultanate with its capital at Delhi. During the next 300 years, the Delhi Sultanate subdued Hindu kingdoms as far south as Tamil Nadu and Bengal.

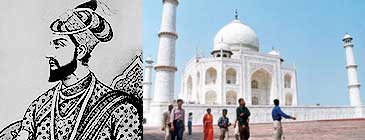

In 1526, Babur, a descendent of the Mongol warrior Tamerlane, founded the Mughal Empire. Babur’s son, Humayun, conquered the Delhi Sultanate and his grandson, Akbar, extended Islamic rule over most of the Indian sub-continent. The Mughals pacified their non-Muslim subjects by extending religious tolerance and administrative opportunity. Mughal domains reached their furthest extent under Aurangzeb (1618-1707). With Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, the empire’s political unity crumbled, but the Mughal impact on India proved lasting. By 1858, when Great Britain formally ended the Mughal reign, some areas of India — such as Punjab and Bengal — had lived under Muslim rule for centuries, developing sizeable Muslim populations through conversion and intermarriage.

1751 – 1947: British India

From the 15th through the 18th centuries, European activities in India centered mostly around trade and evangelism on the Indian coasts. In 1751, however, the British victory over the French at Arcot established Britain’s dominance among the European powers in India. Six years later, Britain initiated the conquest of the sub-continent by defeating the Mughal governor of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey. Through the mid-19th century, British conquest proceeded via military victory and annexation, subjecting Muslim and Hindu interest alike. The Mughal emperor accepted British protection (becoming a puppet regime) in 1803. And between 1775 and 1818, Britain also crushed the Hindu Maratha Confederacy, which had been contesting Mughal power in southern India since the early 1700s.

Although submerged, religious conflict remained a powerful force in British India. In 1905, British viceroy Lord Curzon inadvertently set the stage for India’s modern Hindu-Muslim conflict when he partitioned the province of Bengal. The resulting protest amid Bengal’s elite Hindu minority — which stood to lose rents from Muslim majority renters across the new boundary — became violent as Hindu nationalists took up the landowners’ cause. India’s Muslim elite reacted by forming the All-India Muslim League in 1906. This organization, motivated by a concern for Muslim rights, ultimately became the chief proponent for the creation of Muslim Pakistan as a separate homeland for India’s Muslims.

1947: India & Pakistan

From the 15th through the 18th centuries, European activities in India centered mostly around trade and evangelism on the Indian coasts. In 1751, however, the British victory over the French at Arcot established Britain’s dominance among the European powers in India. Six years later, Britain initiated the conquest of the sub-continent by defeating the Mughal governor of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey. Through the mid-19th century, British conquest proceeded via military victory and annexation, subjecting Muslim and Hindu interest alike. The Mughal emperor accepted British protection (becoming a puppet regime) in 1803. And between 1775 and 1818, Britain also crushed the Hindu Maratha Confederacy, which had been contesting Mughal power in southern India since the early 1700s.

Although submerged, religious conflict remained a powerful force in British India. In 1905, British viceroy Lord Curzon inadvertently set the stage for India’s modern Hindu-Muslim conflict when he partitioned the province of Bengal. The resulting protest amid Bengal’s elite Hindu minority — which stood to lose rents from Muslim majority renters across the new boundary — became violent as Hindu nationalists took up the landowners’ cause. India’s Muslim elite reacted by forming the All-India Muslim League in 1906. This organization, motivated by a concern for Muslim rights, ultimately became the chief proponent for the creation of Muslim Pakistan as a separate homeland for India’s Muslims.

1947 – Present: Violent Legacy

Under the leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru, India on January 26, 1950, adopted a new constitution. Providing for a federal union of states under a parliamentary system, it attempted to defuse communal conflict by ensuring all Indians, regardless of caste, ethnicity or religion, fundamental rights. Nevertheless, Nehru and the prime ministers that followed have continued to struggle with the legacy of partition. Exacerbating the lingering bitterness between Pakistan and India were several unresolved territorial issues: upon independence, three princely states had yet to join either Pakistan or India. Two of these, Hyderabad and Junagadh — ruled by Muslims but with predominately Hindu populations — were forcibly annexed by India. In 1949, the Hindu ruler of Kashmir — which was 85 percent Muslim — finally opted to join India, prompting the first of three India-Pakistan wars, one of which resulted in the creation of Bangladesh in 1971.

Today, Pakistan holds one-third of Kashmir; India holds the other two-thirds and accuses Pakistan of supporting terrorism among Kashmiri separatists. (By mid-2002, the two countries, both nuclear powers, were again on the brink of war over terrorism linked to the region.) During the 1990s, the Kashmir problem combined with more ancient grudges to feed Hindu nationalist populism. India’s current ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was helped to power through its endorsement of a militant Hindu plan to demolish the Moghul-era Mosque of Babur in Ayodhya. This destruction was carried out in December 1992. Since that time, Hindu nationalists have continued to press for permission to build a temple in its place. In February 2002, 58 Hindu nationalists returning from a rally in Ayodhya were burned to death when a gang of Muslims set their train on fire. This attack sparked anti-Muslim violence throughout the state of Gujarat during the first week of March, 2002, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Indian Muslims.