Twelve-year-old Bishal attends the government school in Dholka, a small town in Gujarat, India. Every Wednesday, Bishal, a member of the Dalit, or “untouchable” caste, is expected to clean the classroom and playground. Only the Dalits – the term means “oppressed” or “broken,” – are expected to do chores in school. “I have been asked by the teacher to clean the urinals,” Bishal says.

Fifty percent of Dalit children drop out of primary school.

In the village of Dumbraveni, Romania, two schools stand side by side. One is for the general population, the other serves children with “special needs.” Ninety-seven percent of the students at the second school are Roma, a marginalized minority commonly known as Gypsies. “Roma children are placed in classes for children with mental disabilities although there is nothing wrong with them,” says Magda Matache, Executive Director of Romani CRISS, a leading Roma rights organization in Romania. “Segregated schools continue to exist and the quality of education that Roma students receive is very, very low.”

About 23 percent of Roma adults in Romania are illiterate.

Around the world, children from ethnic, racial and linguistic minorities are being left behind in the quest for universal education. The United Nations Millennium Development Goals, a set of targets for international development agreed to at the turn of the millennium, call for universal primary education by 2015. In the past decade, some progress has been made towards that goal — today, nearly 90 percent of children are enrolled in primary school, compared to 85 percent in 2000. But 75 million children are still out of school; of those, the majority are minorities. The U.N. doesn’t track progress based on racial or ethnic criteria, but a new report from Minority Rights Group International estimates that between 50 and 70 percent of out of school children are from minority and indigenous populations.

Around the world, children from ethnic, racial and linguistic minorities are being left behind in the quest for universal education. The United Nations Millennium Development Goals, a set of targets for international development agreed to at the turn of the millennium, call for universal primary education by 2015. In the past decade, some progress has been made towards that goal — today, nearly 90 percent of children are enrolled in primary school, compared to 85 percent in 2000. But 75 million children are still out of school; of those, the majority are minorities. The U.N. doesn’t track progress based on racial or ethnic criteria, but a new report from Minority Rights Group International estimates that between 50 and 70 percent of out of school children are from minority and indigenous populations.

“You see the same thing happening whether it’s with Afro-Brazilians, indigenous people in Australia, among the Batwa in Central Africa, the Dalits in India…” says Maurice Bryan, who contributed the chapter on Latin America to the Minority Rights Group International report.

But without reaching minorities and indigenous people, the goal of universal primary education cannot be met. “It’s impossible,” says Bryan, pointing out the obvious. “Let’s say 30 percent of a population belongs to a minority, if you don’t reach that minority, you’ll never get past 70 percent.”

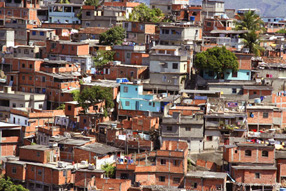

Take Brazil for example. About half of the population is of African descent. But Afro-Brazilians lag far behind Brazilians of European descent, averaging just 6.4 years of schooling. “So if you talk about the Millennium Goals,” Bryan says, “if you just reached the Afro Brazilians, you’d reach the goals.”

Or Romania. Most reports on the Millennium Development Goals don’t even bother to track progress in highly developed countries such as those in the European Union, which Romania joined in 2007. But Snjezana Bokulic, the Minority Rights Group International program officer for Europe, says that conditions for the Roma minority are “comparable to sub-Saharan Africa,” so, while European countries are likely to surpass most of the goals, “a segment of the population will be left out.” As for the goal of universal primary education, only 31 percent of Roma in Romania complete primary school, and Roma comprise between 2 and 10 percent of the population (depending on who’s counting), so the goal is unlikely to be met. “It’s an issue of mathematics,” says Bokulic.

The Millennium Development Goals include a specific provision calling for an end to gender disparity at all levels of education, but there is no similar targeting of disparity based on racial or ethnic difference. Bokulic calls this a “glaring omission.”

Bryan says that no one realized it at the time, but looking back, he agrees that this issue should have been included. “People didn’t used to think that you should pay special attention to women,” he says, “but once they realized that it was necessary, there has been progress on the gender gap. Now the racial gap is the new kid on the block.”

But Bokulic isn’t optimistic about the chances of achieving educational parity for minorities, even if there were a Millennium Development Goal targeting the issue. “Discrimination is entrenched and racism is very difficult to tackle,” she says. “Words are not enough.”

Manjula Pradeep of the Navsarjan Trust Foundation in India agrees. “It’s more on paper,” she says, “but in terms of implementation, the goals aren’t so effective.”

Pradeep says that in order to keep up the appearance of providing primary education, some children are kept in school until the seventh grade, whether or not they can read and write.

While India’s enrollment rate for primary school has reached nearly 90 percent, only about 50 percent go on to secondary school. Of those out of school, 41 percent are Dalits, or members of the lowest caste.

Just last month, India passed a new Right to Education Bill, which guarantees free and compulsory education to children ages 6-14. But Pradeep doubts that this will help keep Dalit children in school. “Teachers ask the children in the lower castes to sit at the back of the room so the other children aren’t defiled by them. They are even told that they can’t drink from the same water fountain,” she says. “They are abused with filthy words, so they drop out.”

Still, many advocates for global education say that attention is finally being paid to the issue of racial and ethnic disparity.

“Governments have begun to see that it’s to their advantage to educate all their people,’ says Steve Moseley, President of the Academy for Education Development, a U.S.-based nonprofit.

“It didn’t come up when they were laying out the Millennium Goals,” says Bryan,” “but once you had the goals, you had the question of why they were not reaching everybody, and then you had the question ‘well, who is everybody.’ So the Millennium Goals may have been responsible for this whole discussion coming to the fore.”

In 2003, the Romanian government got together with the U.N. to set goals for the country that go beyond the standard Millennium Goals – one target is to increase the literacy rate of the Roma population. “The Ministry of Education is finally dealing with this issue,” says Matache, “I think for sure that the participation of Roma will increase by 2015.”

“Brazil is doing far more than anyone else,” says Bryan. “One of the big things is affirmative action; that’s what’s happening in Brazil, and now Colombia is beginning to try it as well.”

According to Bryan, the new Minority Rights Group International report is the first ever to look globally at the issue of education for minority populations. He says this can serve as a baseline from which to measure future progress.

And Moseley believes that that progress is possible. “Even for those facing the greatest disadvantages – poverty, gender discrimination, racial discrimination — it is possible,” he says. “Because I’ve seen tremendous progress, I know it’s going to be possible. Maybe not by 2015, but it’s possible.”