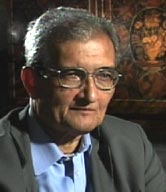

September 4, 2003: Amartya Sen discusses universal primary education with host Mishal Husain.

Mishal Husain: Professor Amartya Sen, welcome to WIDE ANGLE.

Amartya Sen: Thank you very much.

Mishal Husain: It was an article that you wrote a year ago in THE NEW YORK TIMES called “To Build a Nation, Build a Schoolhouse” that inspired WIDE ANGLE to make this film. How do you think it dealt with the issues as you see them?

Amartya Sen: Well, I think it’s a very moving film and the experiences from different countries — some tremendously successful like Japan and others far less successful. I think it’s wonderful to see this other kind of global effort because nothing really is as important in the world as getting children to school, especially female children. And, of course, this is part of the Millennium Development Goals, and it’s the one that I think is more important than any others.

Mishal Husain: And it’s something you felt strongly about for a very long time. Why is it that it captured your passion and your commitment?

Amartya Sen: I don’t think I was original in thinking that. I mean, people have tended to think that. When I was looking at the Japanese [section of the] film, I was reminded of the fact that one of the earliest commitments that Japan had made shortly after the Meiji Restoration in the 1860s was to go whole-hog forward and invest in primary education. Very early commitment went dramatically fast. By 1910, nearly every child of schoolgoing age was going to school. By 1913, Japan was publishing more books than any other country and more than twice as many books as the United States. It’s an experience based on educational expansion. So lots of people have had that idea, but I always thought that that was a brilliant move.

Mishal Husain: It all sounds very idealistic to say, “Of course, education for all is a really important thing.” But tell us, in concrete terms, what is at stake if access to education remains difficult, if children have all these obstacles in getting to school. What is at stake? What are we losing out on?

Amartya Sen: Well, you’re losing out on lots of things. I’ll just mention a few. First, of course, being able to read, write, do your sums really transforms a human being. That a lot of people know. It’s a very ancient thought. Secondly, the ability to get a job depends very much on whether you can follow instructions, especially in the globalizing world today — whether you can produce according to specification, quality control, and so on. Thirdly, your ability to participate socially, read the newspapers, be politically active is very important. Fourthly, and this applies particularly to women, your voice is much more articulate and people listen to you if you’ve been to school. In family decisions, not surprisingly, the biggest impact in reducing fertility is girls’ education.

We did a study comparing the different districts of India — and there are more than 300 statistics — [that showed] dramatically different fertility rates, from five and a half children per couple to close to one and a half children per couple. The two big factors that explain the difference is girls’ education and girls’ employment because the voice of young women in [the] family, of course, is in that direction, because their lives are the most battered by overfrequent bearing and rearing of children. So that’s another.

Mishal Husain: But if all of these things are so self-evident, are all so obvious, then why have we not made more progress? Why is it the case that we have tens of millions, if not potentially hundreds of millions, of children who are out of school today, out of basic primary education?

Amartya Sen: It’s one of the great mysteries to me, actually, because I think the benefit of education has been so clear and people have written about it. And in nearly all the cultures you find that — and not only the Japanese. The writings of some of the great columnists like Adam Smith are full of strong statements on that. If you look at Chinese, Indian, Arabic classics, [there are] great discussions on that. And yet it hasn’t quite happened. I think to a great extent it’s the fact that schooling cost[s] money and quite often when there’s a need to economize, the axe tends to fall very much on that. My friend from Pakistan who started the HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT — a great missionary figure who died a few years ago — used to say (he also had the experience of having been in Pakistani government) that the easiest thing to sacrifice is education. When the government is trying to penny-pinch and, at the same time, trying to keep a defense expenditure and so forth, which are regarded as quote unquote essential, where the education is regarded inessential. So it’s one of those jobs whereby the governments have tried to save money, and they’ll always find some kind of excuse, [such as] the parents don’t want the children to be educated, it’s a hard job, what’s the point of mere education, mere education will not transform anyone’s life. All kinds of nonsense you hear on the subject, more on this subject than on any other.

Mishal Husain: But some progress has been made, hasn’t it? If you look at just the basic illiteracy figures, progress is being made towards eliminating illiteracy.

Amartya Sen: That’s certainly true, and it should go enormously faster than that. Every time you have an opportunity of opening a school, its fee and funding is really relatively small in comparison with the big expenditure, which is basically quote unquote defense. I think if there were fees, progress could be very much faster. But for that we need not only the government in different countries to understand it but the society to put pressure on it, the parents to understand that their desire to have their children educated can actually be realized, and it could make a dramatic difference.

Some of the reasons are more sophisticated. For example, one of the things that comes up in various works [is] how women have their rights systematically violated, even those rights that already exist in the constitution and in the law. [They] are not often used because women can’t read these things and, quite often, they don’t press for their rights. Now that’s getting on to [the] gender equity issue, which is very important, and a lot of people don’t take that seriously, and I think it’s a great folly that they don’t. But one has to bring the multidimensional impact that schooling makes in the lives of people. There’s nothing like it, and I think the importance of it has to be shaken into people’s understanding and determination.

Mishal Husain: What would you say, though, to either individuals or even governments in the developing world that say that our needs are much more basic? We’re grappling with disasters, we need to feed our people, and we just need the basic health needs, that education is something that we just can’t afford to think about right now. It’s something that is for the next stage.

Amartya Sen: I think that would be a very silly argument if that were presented, for various reasons. First of all, if you’re dealing with grappling [with] problems of feeding people, the biggest impact in fertility reduction is girls’ schools. Schooled girls make a bigger impact on that than any other factor — not these various regulations [such as] you have to have one child or that. It turns out that none of these are effective. China, for example, had managed to reduce their fertility to a large extent because of basic expansion of women’s education, not because of the one-child family.

Secondly, if jobs are important, education is important. I think the only thing the government says is not connected with education tends to be this military expenditure. And I agree with that, but I’m very skeptical of the amount of money that goes into military expenditure, not just in the poor countries [but] also in the rich. I think it’s one of the most massive wastes in the world, but education is [at the] other end. It’s the bearer of the greatest fruits that mankind has ever known.

Mishal Husain: Let’s talk in detail for a moment about the gender issues. Why is it that almost everywhere in the world the figures for girls getting to school are almost always worse than they are with boys?

Amartya Sen: Because I think gender inequality is a problem that goes back a long, long time. In human society, as a whole, women have tended to have a kind of inferior position — very often combined with playing up women as great role [models]. In India, for example, [in] the great documents like [the] Upanishads in eighth century B.C., you find some of the wisest [women] making great, learned speeches and then you worship them, but actually don’t do very much about girls’ education generally. So I think there has been a kind of dual presence of pain, respect, and saying you are great, etc., but not providing the basic facilities that make women … able to lead the kind of life that they would like to and that men easily do.

Mishal Husain: And yet there are so many bigger benefits for educating the women of the family?

Amartya Sen: Women’s education has a much greater impact [on], for example, fertility. Men’s education, if our studies are correct, ha[s] almost no impact on fertility. Women’s do. So, by the way, as a man, it’s not to the glory of men specifically that it’s women’s education that reduces child mortality. Men’s education almost has no effect on that. It’s not just that the women are better informed, but, in some way, the priorities of the family, which is certainly bigger part of women’s decisional priorities than men, tend to benefit children too. So I think these are factors, but your question, Mishal, brings me back to that issue. The same reasons for which women’s education means children’s lives are better because they give priority to the family. That family priority — while it’s very good for humanity — has also tended to be one [of] the things that kept women in a relatively less favored position, because women had always been thought of as looking after the family when men go and earn an income and they’re the bread earner and so on. So there is a kind of generation of inequality, [and], on top of the fact, women have pregnancies and periods, [and] when the children are very small, there are greater demands on their time. So one way or another women have had a pretty rough deal in the past, and there’s no reason why that should continue, and any country that has tried to remedy that has succeeded in doing so. So I think it’s very important to emphasize that.

Mishal Husain: Is it slightly unrealistic, though, to have a goal of eliminating the gender gap in things like education, because we know just how hard it is to eliminate the gender gap in so many other issues? And there are always going to be things like childbearing that potentially will change women’s lives.

Amartya Sen: Yes, but I think there’s a danger in seeing all of these as being one thing because gender inequality is not one problem, it’s a collection of problems. There may be countries [where] there’s no gender inequality in schooling, even in higher education, but [where there is] gender inequality in high business. Japan is a very good example of that. You might find cases in the United States where at one level women’s equality has progressed tremendously. You don’t have the kind of problem of higher women’s mortality as you see in South Asia, North Africa, and East Asia, China, too, and yet for American women there are some fields in which equality hasn’t yet come.

So I think one has to see that as a whole lot of inequalities, which have to be dealt with when society gets determined to deal with that problem. And there’s absolutely no reason why at the level of basic schooling that there should be any inequity whatsoever. And [that’s] the first direction to go, [but] that need not prevent you from doing all the other equalities that you want.

Mishal Husain: One of the things we saw in the film about Benin was just what an uphill struggle it can be, particularly for little girls. I mean, the little girl in Benin was the only child in her family, only girl in her family, to go to school really against great odds. I mean, this is really like swimming against the tide.

Amartya Sen: I think that’s exactly right. I thought all the films were wonderfully watchable, and I thought the Benin film, to some extent, slightly began by saying that nearly every woman in Benin had to go on to doing voodoo. I think this was an anthropological exaggeration. It wasn’t quite the case. It ended up that the culture being so adverse rather than treating it as a problem in the way you just presented it, namely [when] there was no one educated before, it’s very hard for anyone to start getting an education. It’s a big problem. I think this problem was in the India film also, it made the parents so negative. Now I know there exist parents [who] would be against girls’ education. But study after study statistically have borne out that that’s not the case — even in areas like the most depressed region of India in terms of female education, namely Rajasthan, which has [one of] the lowest female literacy [rates] in India. Even there, 80 to 90 percent of the parents would like their girls to go to school. And indeed, about 80 percent would like them to be made compulsory.

So I think it picked a very exceptional family and operated on that to make a case for the night school. But I think it’s a mistake because basically one has to accept the adversity of the first-time child education. And, at the same time, one has to recognize that across the world, in Africa, Asia, Latin America, everywhere, there is a widespread recognition on the part of the parents, too, that the children’s life will go much better by being educated. And that applies to girls as well as boys.

Mishal Husain: Even for parents who are illiterate and have no education themselves?

Amartya Sen: Yes. I was fortunate in using my Nobel money to start the Pratichi Trust in Bangladesh and in India. And the Bangladesh one is concerned with girls’ education. The India one had been basically concerned with primary education. And one of the things we find, even when there are some cases … actually the percentage of girls going to school is quite high in Bengal, nearly every girl is registered. But when you ask the question of absenteeism (often girls drop out), the parents absolutely are keen on the girls going to school, but their argument will be logistic ones, that some of the schools are one-teacher schools and quite often the teacher isn’t there. There’s a high level of absenteeism, which is often high when the children come from very backward classes, which don’t have the economic and social muscle.

And then you work in the field, you send your six-year-old daughter to school, you don’t know what’s going to happen to her if there’s no teacher. So I think rather than targeting parents as a kind of devil of the [India segment], one has to see why is it that it happened that despite the great interests that parents have in sending girls to school, it sometimes doesn’t happen and what can be done. And that requires schools being closer, there being more of them, and there being more than one teacher to reduce the teacher absenteeism, and having the voice of the parents in the running of the school. It’s strongly important.

Mishal Husain: You called for a global initiative, a global approach, to dealing with the lack of access to education. But looking at that film, there are so many different reasons why it’s hard for children to get to school. It can be the fact that the parents are not supportive. It can be that the school is far away, it’s difficult to get to, it’s expensive, whatever it is. Given all those different reasons, is it possible to talk of a global initiative that somehow could bring one approach to attack all of those issues?

Amartya Sen: I think it is, actually, because, you’re quite right, adversities come in different forms. But it is possible to have a global coordinated program. We’re also quite lucky [to have] the United Nations. I think we’re lucky to have Kofi Annan as our Secretary-General, as our leader, in providing a kind of format [for] a number of other institutions in the world, including NGOs. I was the honorary president of Oxfam, and I know how committed Oxfam is to all this. Many of the other institutions are similarly involved, and also the World Bank is very keen on education now. It has not been so in past, often in primary education, but it’s a big priority now. I think we can have a global initiative. The advantage is, first of all, the financing issue will have to be dealt with, which is a big problem, but it’s sometimes made bigger than, in fact, it is. Secondly, I think we need social cooperation at every level.

Mishal Husain: Learning lessons from one country for another?

Amartya Sen: That too, and within the country. In the film about India, Rajasthan, the most backward state, was picked. If you look at the other end, Kerala, educational performance is no different from Japan, or Himachal Pradesh, which was like Rajasthan and today is like Kerala. And the transformation that was brought about in 25, 30 years also shows how things can be learned easily from one country and within a country, from one place to another. So I think there’s a lot to be learned, but I think the advantage of a global initiative is that it puts it as a priority for the society, not just the government, but the society. I think in those countries, including my own in India, where I think primary education has been badly neglected by successive governments, I blame the opposition as much. Why have they allowed the government to get away with it?

Mishal Husain: But when you talk about a global initiative, then inevitably it becomes a numbers game. People basically ask the question, how much money is it going to take to solve this problem? And one of the things that’s striking in the film is the kind of hands-on commitment that’s needed in a country like Benin, for instance, where the little girl was helped in her journey to school by a mediator, by a mentor. That’s the kind of hands-on commitment it actually takes. And when one talks about the global initiative, can’t one just get lost in the numbers and the dollars?

Amartya Sen: I think that there are two things, Mishal, on that. One is that the Benin girl had a problem that partly connected with the distance of the school. If there are more schools closer to home, that problem will not arise. Secondly, oddly enough, it’s the number[s] game on financial cost that you very rarely hear from those who are opposed to such [an] initiative because the money isn’t very large in comparison, especially when you compare [it to] military expenditure. It’s really a relatively small expenditure. So those who are against it tend to emphasize other things: the parents are not keen; they wouldn’t let their girls go to school, which is really one of the old chestnuts, which needs to be exploded. Or saying organization is difficult: can you imagine 200 million kids going [to school]? Well, you can imagine. [To organize a school] looks much more difficult in theory than it does in practice. No, I don’t think any of the counterarguments work, and, therefore, it’s an ideal situation for a global initiative in which we can put our hands together.

Mishal Husain: So if the parents’ commitment is overall there, if the UN leadership is there, what’s your verdict on the cooperation and commitment of governments?

Amartya Sen: Well, that varies tremendously, because, by and large, the governments have tended to be very reluctant to spend money on that. One of the difficulties is that in terms of the kind of visibility of outcomes, war — whether it be between Pakistan and India or between Eritrea [and] Ethiopia or in the Balkans — is a much more eye-catching thing. Defense, you can’t let the country neglect its effects, in very rich countries, too, like the United States. And that has a much greater kind of visibility. There are other advantages to school, too. Just mixing with other kids makes the difference because people have different customs and the fact [is] that the world is a varying place. The understanding that women are not inferior across the world, it’s something that you can get from school, not only from the book but also from chatting with other kids. It’s a big impact. One of the curious things is that even when — and this we found from studies — the schools are doing pretty badly in terms of their education, about mathematics and literature and language, going to school transformed people because I think the action of schooling, the activity, is very important. But it’s not something that really captivates the government and/or the opposition party. So I think there is a real difficulty there, and if I were to put my finger on it, I would put two things. One, to make the governments more convinced, and quite often the governments are not even representative governments. And, secondly, to make the private sector, the business groups to take a greater interest. It’s ultimately — may not be immediately — in the interest of world commerce, world trade, world business, that everyone is educated. I mean, the great example is the first country that this film began [with], … Japan.

Mishal Husain: But also the East Asian tiger economies, which all made it a priority.

Amartya Sen: They were driven to a great extent by the Japanese experience, but take South Korea. South Korea at the end of the Second World War had a very low level of literacy. But suddenly, like in Japan, they determined they were going in that direction. In 20 years’ time, they had transformed themselves. So when people go on saying that it’s all because of perennial culture, which you cannot change, that’s not the way the South Korean economy was viewed before the war ended. But again within 30 years, people went on saying there’s an ancient culture in Korea that has been pro-education, which is true. Nearly everywhere Buddhism went, there had been a higher level of literacy, even in miserable Burma, not to mention Thailand and Sri Lanka. So there are culturally predisposing factors; Buddhism certainly has been one, but the biggest is made by commitment of the modern government to try to do something in what is, after all, the biggest curse of humanity.

Mishal Husain: If you look at India, I think it’s a country of so many extremes when it comes to education. On the one hand, it’s been at the forefront of the IT boom, it’s had a huge brain drain, people like yourself, for instance, very, very prominent Indian intellectuals; and, on the other hand, it’s amongst the regions, along with sub-Saharan Africa, that has the worst record on primary education.

Amartya Sen: By the way, I don’t accept brain drain partly because I don’t accept the brain bit, but also I don’t accept the drain bit on grounds that … I go to India about five or six times, to Bangladesh, to Pakistan, whenever I can. But you’re quite right that there is a big contrast. The higher education has always appealed to the South Asian social leaders across all the countries in South Asia. But primary education has been neglected. The oddity, by the way, is if you look at the contrast in India, there are some areas like Kerala where there’s a long history of educational development.

Mishal Husain: Do you think the UN will meet the goal that it set, universal primary education by 2015?

Amartya Sen: It’s a very difficult goal, but I think it’s just right that it has taken such a goal. It will really depend on how much cooperation comes from the world community because the UN can set up goals, [but] it doesn’t have the resources nor the unilateral ability to execute its goals. So the goals are an invitation to the world.

Mishal Husain: Governments need the commitment?

Amartya Sen: Government, international organizations, NGOs, all these have to respond to it. So the UN goals are to some extent letters of invitation. And the answer to that is if the invitations are taken, yes, you could meet those goals. If the invitations are not taken, then it would not [happen]. I think the UN’s role — especially since it’s not an extremely rich fund, and that’s to put it mildly — is mainly to act as a leading thinker of the world in terms of how to think about the future. If institutions like the World Bank as well as … private institution[s], which can provide money and support themselves, come in and if the government responds to the UN invitation to take on this as their biggest priority, I think, yes, it can come certainly very close to meeting it. It’s a question of [whether] one [wants to] be pessimistic or optimistic on that. Now I’m by nature optimistic, and I hope that it still will happen. So far the responses have not been as good as one had hoped.

Mishal Husain: But it wasn’t an unrealistic goal in the first place?

Amartya Sen: It’s not an unrealistic goal, and that’s the way the UN can work. I think if you are in Kofi Annan’s position, in a sense he’s the leader of the world and, at the same time, he hasn’t got the funds to do it so he has to invite others to help him to do it. And that’s what he’s doing. And I think one thing that I find very irritating is when people say the UN isn’t doing it. Now the fact of the matter is that UN has this role and others have to really help in doing that, and it’s that which has been lacking in this. And it’s that which has been lacking in this. Now, I’m not really hopeless yet because I think it can pick up, there’s a lot of interest, certainly some governments have responded and others could. There’s still some time left, a dozen years left, until that goal comes to fruition. And one hopes we’d make a radically impressive progress at least in that direction, towards fulfilling that goal.

Mishal Husain: What is the role of the United States in trying to help in this goal of achieving universal primary education?

Amartya Sen: Well, I think the United States can do a lot partly because it does a lot of funding of things in the world. In percentage terms, it may not be the biggest owner as a share of national income, that goes much more to many European countries, but in absolute terms it provides a lot of funds. Funding is a very big thing and educational priority could make a dramatic difference. I think also the United States can play a very important part in bringing this into dialogue. [The] USA has been immensely successful in making the determination to deal with terrorism [as] a factor in the global world and, similarly, if it took a similar interest in education, it could make a difference. I think one big thing about the United States is that the American population, they may be excited about Iraq or one thing or another, but basically has had a great deal of interest in humanitarian causes both within the country and abroad. Even when they criticize the mechanism to which it flows. But I think to bring that into the dialogue and to make it a concern will not only affect more how Americans think, but how American thinking also affects how the world thinks. That’s very important. There is also another side I think worth bringing in, mainly that there’s a moral obligation on the part of the United States, I believe, not just because it’s rich — and [the] rich do have obligations — but there’s also the fact that among the major evils in the world that exist today is, of course, the debates that occur as a result of military conflict across the world. I don’t mean … al Qaeda. I mean the civil fights, the civil wars that go on across the world. And in that, of course, all the rich countries, the so-called G8 countries, the United States in particular, have played a major part. Indeed, when I last looked at the statistics, 80 percent of the export of armament in the world comes from the G8 countries. [The] United States alone exports about 50 percent of the world’s armament, [for] which, of course, there has to be buyers, and the buyers are very terribly keen, very often military dictator[s] or sometimes not military dictator[s] but for military purposes. But the sellers are also promoting this trade. And two thirds of the arm exports go to developing countries. I’m in favor of putting a control on it, a ban on it. Kofi Annan also had a proposal about banning illegal export of small weapons, which the U.S. government did not accept. But these are issues on which I think Americans ought to rethink, the U.S. government ought to rethink. But on top of that, I think just as armament had a major impact of a negative kind in the world, education is something which has a major impact of a positive kind in the world. And I think the American population, with its humanity and with its concern about the future of the world, has a real reason to think about what it can do to help the world in expanding education. After all, the American society has been also based on the premise of expanding education very early. That’s been [one] of the main sources of success of the Americans. And there is something that the world can learn from it and also be assisted by the United States along with Europe and the rest of the world. I really hope that this is an issue that engages the American public.

Mishal Husain: But in the reality that we live in, this era of the war on terrorism, could you perhaps make a security argument for persuading the G8 to put more money towards education, saying this is all part of the process which potentially can make the world a safer place?

Amartya Sen: I’ll say two things on this. One is that that’s not the best way of justifying education because education makes us the human beings we are. It has major impacts on economic development, on social equity, gender equity. In all kinds of ways, our lives are transformed by education and security. Even if it had not one iota of effect [on] security, it would still remain in my judgment the biggest priority in the world. With having said that, my second point, yes, indeed, even from a security point of view, both the spread of education as well as the content of education, what do people learn about each other? There is hardly any attempt yet to look at the curriculum. Quite a lot of these schools are centers of generating hatred, we know that. But the fact that schools can actually be a major factor in cementing the world is a factor that’s worth considering, the fact that we all have a shared human identity in addition to many other identities. Again, the identity of just one thing, the “clash of civilization” view that you’re a Muslim or a Hindu or a Buddhist or a Christian, I think that’s such a limited way of seeing humanity, and schools have the opportunity to bring out the fact that we have hundreds of identities. We have our national identity. We have our cultural identity, linguistic identity, religious identity. Yes, cultural identity, professional identity, all kinds of ways. Just to take an example: a young Arab man, a Muslim Arab man, wanting to be patriotic, one line is to play up Islam, and there’s a tremendous amount to be proud of there. And yet, the Arab world is also the world that produced some of the greatest improvements in mathematics and in science. Even today, when a Princeton mathematician does an algorithm, he may not remember that “algorithm” derived from the name al-Khwarizmi, who is a ninth-century Arab mathematician. Now, an Arab activist can take pride in the Arab heritage of mathematics and science or he can take pride in his religion, and there’s pride to be taken in both. But one of them could be exploited much more easily and has been in the context of world conflict. And the other is very difficult to do on the grounds that science and literature and mathematics have been among the uniting factors in the history of the world. And that’s why basically education is so centrally important. It can really transform the insecurities in the world into a bigger vision of what we are as human beings.

Mishal Husain: I think one of the difficult things when you’re trying to raise the funds for education can be all the competing issues that demand the attention of donors. It’s education, it’s disaster relief, it’s health care, it’s food aid. How do you make education stand out or how do you package it as part of a whole approach to the developing world?

Amartya Sen: Well, I think education has a bigger impact on the lives of people than absolutely anything else. That’s the thing to recognize. It’s not just a question of donor priorities, it’s also the priority of the domestic country and of the global world, including NGOs as well as social organizations of various kinds. If you think about the dramatic impact, it makes human beings more articulate. It transforms people. You can think differently about the world. It makes it possible for you to get jobs. It makes a dramatic difference. It generates a social equity that we need. It could be a great vehicle for gender equity. It allows people to see what your rights are by reading. Quite often women, for example, may have rights that they are not in the position to actually make use of. In absolutely every way, our lives are transformed by education and basic education in particular. So I would have thought that in any kind of system, to say that the priorities don’t include education is a mistake, whether it’s [at the] domestic level or at the global level. Now it’s true that there are disasters … the disasters are important, and we have to deal with them and there’s an urgency. Sometimes one makes a distinction between urgency and importance. And while disasters are urgent, the basically most important thing is education. And that’s what gives it ultimately urgency too, because unless you do it now, this important thing gets again and again postponed. So it requires a vision, which I very much hope that we are able to generate, and I’m delighted you’re doing the program. And I think the basic interest in that is wide felt. I think the world is in a position to hear these arguments strongly and clearly right now because there’s a lot of rethinking going on about how to think about the nature of the global society.

Mishal Husain: How would you explain the difference that we’ve seen in the progress made in East Asia, where education has been so remarkable, and in South Asia, which is one of the regions that really has the worst record on primary education?

Amartya Sen: Yes, I think it’s a very frightening record. Some of the difference is historical. I think East Asian countries, I think they’re very fortunate to have Buddhism survive as a strong influence because right from the time when Buddha himself, 2,500 years ago, made the point about the importance of education, and the word “Buddha” also means enlighten[ed] or educated. So all the Buddhist countries, not only Japan and Korea and China and Hong Kong and Thailand but also even Burma and Sri Lanka, had a higher level of education. But that wasn’t the big difference. The big difference that came, came after the war, when there was a strong determination in East Asia to go in that direction. South Korea from a country that had relatively little primary education became close to universal literacy in the course of 25, 30 years, in a way trying to replicate what Japan had done earlier. They were learning to some extent from the Japanese experience too. So I think, in a sense, the East Asians were following a path, which all other countries including South Asia could follow but chose not too.

Mishal Husain: But was it the key to economic development and economic progress in East Asia?

Amartya Sen: Oh, absolutely so, I think there’s no other way of understanding that dramatic expansion of the economy as well as the social change that occurred in Japan, in Korea, in Hong Kong, in Singapore, and to some extent in China without education. And at the lower level, but still at a firm level, it applies even to other countries like Thailand. Its economic development was driven by educational expansion. That has been a very dramatic factor, and South Asia had been pretty miserable in not learning from that experience. And there might be slight differences in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, but basically that lesson has not been quickly [learned]. … There are big differences within India, of course, because being a big country, you have on one side states like Kerala and Himachal Pradesh where every child, nearly, goes to school now, where there are other states like the one that you had in the film, namely Rajasthan, which is on the other end, where [a] vast majority of the girls don’t go to school yet.

Mishal Husain: If you talk about education as being the key to breaking a cycle of poverty, how do you deal with the catch-22 that you can see in so many parts of the world, the basic paradox that education might be the key to breaking out of poverty, but it’s poverty that provides all these obstacles to education?

Amartya Sen: You know, I don’t think poverty provides that much of an obstacle to education as one thinks. I think the bigger obstacle to education is the fact that it’s a very hard thing to do for a first-generation schoolgoer. Because not to have parents at home who can help you, motivate you, is a problem even when the parents are in the abstract very keen on children being educated. It’s very hard for them to know precisely what’s going on. In our studies, we find parents tearing their hair, wishing they could help the kids a bit. Poverty isn’t [the main obstacle] for several reasons. First of all, schooling isn’t very expensive; it doesn’t require a great deal of other equipment. Secondly, while it’s the case that poorer countries have less money and less income, it’s also the case that since it’s labor intensive, by and large, the salaries are not very high. Now sometimes countries are counterproductive. In India the schooling salaries have dramatically gone up compared with, say, agricultural labor salary. And that’s a main problem of educating the agricultural laborers too, when school is much more expensive than it need have been. But even then it’s not a very big expenditure, given the fact that basically we waited so long. So that poverty is not really as much of an obstacle to educational expansion as it’s sometimes made out to be.

Mishal Husain: But then how do you explain the fact that in one of the countries we saw in the film, in Kenya, there’s been this explosion in the number of children going to school basically because overnight the government decided to make basic education free?

Amartya Sen: Because when I say that the finance is not the cost, I don’t mean it’s not the cost for the family. If the children’s parents have to pay for schooling out of your own pocket, that is a very big deterrent. I’m not talking about that at all. I was talking where the government has the money to do it. So the Kenya case is exactly my point. Once Kenya decided they wanted to do it, they could, because the funding wasn’t all that much of a barrier. It is a big barrier if you are at the bottom layer of society, don’t know where the next meal is coming from. It is not a big barrier of taking the rich with the poor in a big society to provide schooling for all. So it has been seen as a burden of poverty that visits the individual, but it’s not something that need deter the states because the funding that’s needed to organize school [on] a systematic basis is not very large. And then on top of that, if there’s global help, whether from the United Nations, the World Bank, and other countries, obviously that makes things much easier.

Mishal Husain: What about the argument for quality, because we’ve talked a lot about just getting children into school. Is the quality of the education that they receive something that one can worry about at a later stage? Is it just vital to get them through the doors of that classroom?

Amartya Sen: Well, I think yes and no. I think it is vital to get them in the classroom because one of the things that any kind of studies bring out is that the mere act of schooling — getting together, the organization involved, going to classes on time, and there’re things being taught, sitting down with others with different backgrounds, chatting with them, and, sometimes when there are big barriers, eating together when there are school meals, which are big things together with a big social impact — they themselves have a major effect. Secondly, I think … part of the answer is that there is no choice here, really. That is, there’s no reason why one need not look at the content of education just as one is expanding the availability of school, because it doesn’t cost more money to get them [a] better education. It requires better textbooks, it requires a vision, it requires a determination, but it’s not very expensive to do that anyway. The third point is — and that’s normally [at] a kind of sophisticated level — that aside from the three Rs, reading, writing, and arithmetic, there is also the question of, I think very important in today’s world, to recognize that each human being is a citizen of the world. We have many identities, of which one of the identities is our human identity. And that’s something that the schools can provide, but that requires again a vision rather than being centers of hatred. It could be an enormous opportunity to give that mission. Belonging to humanity is a great thing for us, and I think the schools can do it. So I think we can look after the quality of education on the school even as we expand the availability of schooling.

Mishal Husain: What does this issue mean to you personally, because you cared enough about this as an issue to donate your Nobel Prize money to the cause of education. Why did it matter so much to you as a person?

Amartya Sen: Well, firstly, because I have been in education throughout my life. I was even born in a campus. But also when I was in high school, I started some night school. I was very nostalgic to see the night school in Rajasthan. I don’t think the Indian education problem could be solved in the night school way, but every little bit counts and, of course, when I was 14 and 15 we started a night school in the local, very depressed area around our school. And I guess some of the most delightful moments of my teenage years were when I was trying not just to educate myself but trying to educate others. And I could see how the lives of children could be transformed in that. So when the Nobel gave me an opportunity to do a little bit — very tiny bit, I might say, because you know it’s not a lot of money — it gave me an opportunity to start that in Bangladesh and India to do something about the education. It’s the one respect in which I felt that I could have a little bit of an impact on the world. And I really do believe that education, despite this massive potential in transforming human lives, has not received the kind of attention that people should have given to it. A number of organizations which have been involved, like Oxfam, began as a feeding organization. … [The] fact that it went very much in the schooling direction was [an] enormous joy for me and source of satisfaction.

Mishal Husain: What WIDE ANGLE plans to do with the children you saw in that film is to go back and check in on their progress and see how their schooling develops after this first year. Having seen those six children, which out of them do you think is most at risk in terms of their education?

Amartya Sen: Well, I’d first say the condition for my trying to answer your question is that you have to keep me informed as to what happened to these kids, because I’m really excited and interested in that. I think … maybe I’m being culture biased because I know the adversities in India. I think that particularly in Rajasthan, which is a very difficult area from an educational point of view, the fact that Neeraj is going to a night school is a vulnerable thing. The night schools are very difficult to maintain because, first of all, it’s an unusual hour, people are worried about safety. Parents are, in any case, worried about girls’ safety anyway, and it depends on who’s running it. Quite often these NGOs are run by excited people and then when somebody goes away, transfers to some other job, much will depend on who would follow. So I would say night schools are inherently more fragile as a system. It’s not like the robust, standard, classically tried for thousands of years day school, when people go in the morning and have a bit of learning. So I would be worried a little about Neeraj and I hope that proves to be quite wrong. I hope also she transfers to day school, actually, because that’s the way to move ahead. I thought the Benin girl is, of course, dependent on some help that she’s getting. So there is vulnerability there. Obviously there’s less concern in some of the others. And Kenya I think is a very, very warm story. So, yeah, that’s, I think, the way I would answer that.

Mishal Husain: Well, we’ll certainly keep you up to date.

Amartya Sen: You have to keep me informed.

Mishal Husain: Professor Amartya Sen, thanks very much for joining us on WIDE ANGLE.

Amartya Sen: Thank you very much indeed.