Islam, as described by Muhammad, was a straightforward faith, demanding of its adherents only that they acknowledge a set of basic beliefs: that there is only one God, and that God is Allah; that believers must submit completely to God; that God is revealed in the Qur’an; that Muhammad is Allah’s final prophet, and that all believers are equal before God. Beyond that, believers were called upon to observe “sharia” (the law as defined by the Qur’an), and to conform to the five “pillars” of the faith: public witnessing of one’s faith, daily prayer, charity, fasting during the holy month of Ramadan, and making pilgrimage to Mecca.

| Afghanistan Pop.: 28,513,677 % Shia: 19% % Sunni: 80% Algeria Azerbaijan Bahrain Egypt Iran |

Iraq Pop.: 25,374,691 % Shia: 63% % Sunni: 34% Israel Jordan Kuwiat Lebanon Libya |

Morocco Pop.: 32,209,801 % Shia: — % Sunni: 99% Oman Pakistan Palestinian Territory Qatar Saudi Arabia |

Sudan Pop.: 39,148,162 % Shia: — % Sunni: 70% Syria Tunisia Turkey U.A.E. Yemen |

Muhammad established no church or institutional structure for Islam; indeed, the faith’s basic notion that all believers were equal before God seemed to rule out the notion of a priesthood. But Islam was a social and political movement as well as a religious one, and as it developed, a complex set of institutions grew with it, which over time took on an increasingly religious significance. And as the Arab empire expanded, Islam incorporated elements of the cultures it encountered, giving rise to varying schools of interpretation of the texts of Islamic belief: the Qur’an, the “sunnah” (the exemplary words and deeds of Muhammad) and the “hadith” (the records kept by Muhammad’s companions).

With the rise of religious institutions and the expansion of Islamic scholarship, doctrinal arguments developed, which led to the development of a number of sects and schools of thought. But the most important schism in Islam — the event that split the faith into the majority Sunni and minority Shia branches that persist to the present day — took place at the religion’s very beginnings.

The Caliphate

Muhammad died in 632 C.E. without leaving a son and heir, or clear instructions on who would succeed him. Under his leadership, Islam had become not only a faith, but the driving force behind an expanding Arab empire. Following tribal tradition, three groups of Muslim leaders — those who had accompanied Muhammad on the “hijira” (the flight of the early Muslims from Mecca to Medina), the civic leaders of Medina who initially supported Muhammad, and the prominent families of Mecca who had become converts upon Muhammad’s return — met to decide who would act as head of the growing “ummah” or Muslim community.

The discussions split along partisan lines, which had roots in an existing rivalry between the closely related Hashemite and Umayyad clans. The Hashemites (the clan to which Muhammad belonged), supported Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali (he’d married the Prophet’s daughter Fatima), while the rival Umayyads backed Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s father-in-law. Ali’s followers became known as the Shia, from “shiat Ali” (party of Ali); those who supported the Umayyads came to be called Sunnis, from “Sunna” (one who follows the word and deed of the Prophet).

Eventually Abu Bakr was appointed to the new position, known as the Caliphate (from “khalifa,” the Arabic term for successor), and assumed spiritual and political leadership. The new position was primarily secular: The Caliph led the Islamic community, but was not believed to possess any kind of divine power or prophetic ability, since Muhammad’s teachings had established that he was the final Prophet.

While Abu Bakr’s reign lasted only two years (he died in 634), his successors, Omar and Uthman, continued to expand the empire, moving into Iran and Egypt. But the political struggles between the clans continued, and both the second and third Caliphs were assassinated.

In 656, Ali was chosen as the fourth Caliph. He would be the last of the “rightly guided” Caliphs — the men who had traveled and studied with Muhammad — and his ascent to the throne triggered Islam’s first open civil war.

The Schism

Muawiyah, the Umayyad governor of Syria, challenged Ali’s authority as Caliph, and the empire fragmented, with both men claiming to be Caliph. Muawiyah argued that the Caliphate should continue to be decided by a consensus of the faithful, while Ali’s followers maintained that the Prophet’s bloodline should take precedence. Meanwhile Abu Bakr’s daughter Aisha — Muhammad’s widow — charged that Ali had been an accomplice in Uthman’s murder and led her troops against his. Finally, in 661 C.E., Ali was assassinated by the Kharijites, a breakaway sect whose members rejected both Umayyad and Hashemite claims to the Caliphate.

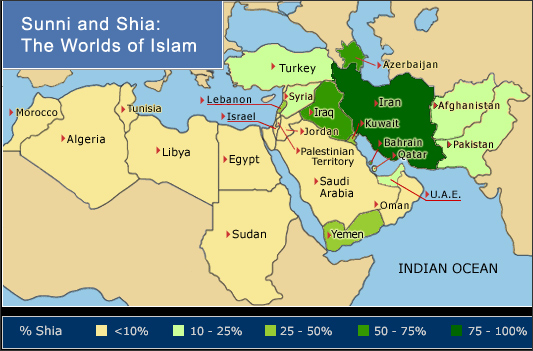

Ali’s eldest son, Hasan, who was uninterested in politics, rejected the Caliphate, and Muawiyah claimed the position, moving the capital to Damascus, Syria and ending the debate over succession. The Umayyad dynasty went on to rule for a century, expanding the empire as far east as present-day Pakistan and as far west as Morocco, even taking control of Spain in 711. The Umayyads consolidated Islamic rule over what we know today as the traditional center of the Islamic world as seen in the map above: North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia. The Caliphate itself existed (with varying degrees of power) as a secular authority in the Islamic world until 1924, ending only when Ataturk abolished it as part of the secularization of Turkey.

The Shia, meanwhile, rejected the authority of the new Caliph, claiming that Muawiyah and the Umayyads were usurpers. They believed that membership in the Hashemite line — in particular descent through Ali and Fatima — should be the basis of authority within Islam. Ali’s younger son, Husayn, gained a following in what is now Iraq, becoming popular with recent Persian and other Central Asian converts to Islam, who felt that the Umayyad Caliphate was treating non-Arabs as second-class citizens. A second civil war erupted as Husayn finally acted, pressing his claim to the Caliphate and leading a rebellion against the Umayyads.

Husayn’s small force faced the Umayyad army at Karbala, in what is now Iraq. Woefully outnumbered, he was killed along with all of his followers; his infant son died later, ending the Hashemite claim to the Caliphate. The Shia, however, did not disappear, but evolved into an oppositional movement within Islam, with its own leaders, doctrines, and ceremonies.

The deaths of Ali and Husayn came to be central parts of Shia spiritual life — the Shia have come to see both men as divinely inspired martyrs who died defending the true faith of Islam rather than victims of a struggle for political power. Shia faith has a deep regard for martyrdom, and has incorporated mourning rituals, “passion play” theatrical reenactments and processions, and other passionate, demonstrative traditions that are absent from Sunni practice.

Perhaps even more importantly, the Shia and Sunni traditions disagree strongly on two related matters: the question of divinity in the succession from Muhammad and the role of the clergy in the practice of Islam. While the Sunni believe that all humans, past and present, have had the same relationship to God, the Shia hold that Ali and the eleven leaders of the Shia faith who followed him — the twelve Imams — were divinely inspired and infallible in their judgements. The Twelfth Imam is believed not to have died, but to have passed into “occultation,” to return someday as the “Mahdi” or guided one, to lead a perfected Islamic society.

Most Shia — including the large Iranian Shia population — recognize the twelve Imams, and are thus referred to as “Twelvers” (minority branches of the Shia traditions only recognize the line up to the Fifth or Seventh Imams). The Imams are treated as saints, and their tombs have become pilgrimage sites. Given the messianic belief in the return of the Twelfth Imam, a hierarchical organization of clerics (which some historians have compared in structure to the Catholic Church) grew up to manage Islam until his return; these clerics are themselves understood to hold an elevated spiritual status.

This is in distinct opposition to the Sunni tradition, in which the “ulema” (clerics) function simply as prayer leaders and legal interpreters, recognized only for their learning and expertise in jurisprudence. Furthermore, the Sunni strictly oppose the “saintly” role the Imams play in Shia faith, since in Sunni interpretation this is equivalent to the elevation of humans to godly status, and thus forbidden.

Some minority Shia sects have added two further “pillars” — jihad (understood generally as the duty to perform good works) and allegiance to the Imam — but most of these groups have disappeared and the associated concepts have slipped out of practice. Mainstream Shia legal belief also includes a concept known as “temporary marriage” which the Sunni see as an endorsement of extramarital affairs. Overall, however, Shia and Sunni adherents agree on the core beliefs of Islam: the Qur’an and the Five Pillars. Neither Sunni nor Shia faith has remained static — the body of Islamic jurisprudence includes a mechanism similar to legal precedent, in which new ideas can be incorporated into Islamic tradition using analogy with decisions described in the Qur’an, sunnah, or hadith.

In the twentieth century, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini introduced a major innovation into Shia law, though it has only taken root in Iran. Khomeini’s concept of “velayat-e faqih” (guardianship of the jurisprudent) calls for government and civil society to be guided directly by the clergy. Put into practice following the 1979 revolution, this has resulted in Iran’s hybrid government, in which an elected parliament and president are subject to the power of a body of appointed clerical officials.