El Salvador: Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13)

Mara Salvatrucha, otherwise known as MS-13, formed in Los Angeles during the 1980s when refugees of El Salvador’s 12-year civil war settled in Southern California and fell into life on the streets.

During the last two decades, with the aid of U.S. immigration policy, MS-13 has spread across Central America. Members are primarily Salvadoran; most were young war refugees when they came to the United States. When the civil war came to an end, however, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service ended the special refugee status it had reserved for Salvadorans seeking asylum in America and began deporting undocumented immigrants by the thousands.

Many of the deportees were returned to El Salvador (or other Central American countries) well informed by a criminal lifestyle, including the trade of guns and crack cocaine, that was previously foreign to the region. Furthermore, most were so young when they left El Salvador, they had no connections in the country beyond the gang affiliations they had formed in the United States. This led to the flourishing of MS-13 in El Salvador and its eventual spread throughout Central America, where it is said to have at least 50,000 members.

The deportation effort likewise proved ineffective at diminishing MS-13’s activity within the United States. Most members are said to return soon after they are deported, and it is estimated that there are now as many as 10,000 members in more than 30 states: in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. especially, but also in the suburbs of Maryland and even rural Virginia.

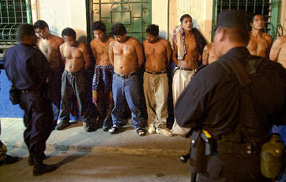

Members of MS-13 are noted for the tattoos that cover most of their upper body, even their face, in gothic script lettering — as well as for shaved heads and goatees.

By 2000, officials in Central America began to crack down on the increasingly violent gang and its chief (and purportedly better-organized) rival, the 18th Street gang, implementing a series of “zero tolerance” laws that gave governments the right to imprison suspected gang members for simply wearing tattoos associated with gang membership. Human rights groups have decried such hard-line policies, which have led to overcrowded prisons that are now effectively training grounds for gang members.

Some Central American government officials have accused the U.S. of causing the gang problem with its previous deportation policy. In February 2005, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security implemented a project called Operation Community Shield, designed to work in conjunction with Central American governments and law enforcement agencies. Ultimately, the gangs are an international problem related to intense poverty and a severe lack of education and opportunity in a region that has yet to recover from a devastating civil war.