by Edward E. Telles

Download the PDF here.

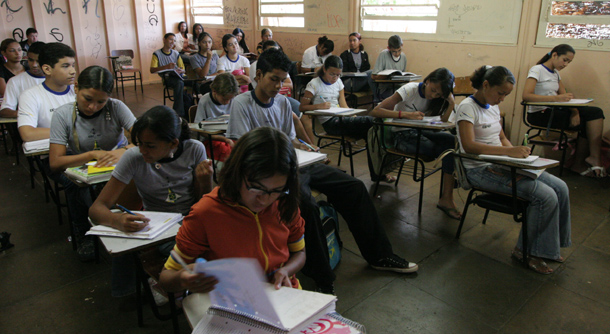

photo credit: Ademir Rodrigues

In 2001, on the heels of the United Nations Conference on Racism in Durban, South Africa, several Brazilian institutions established race-based affirmative action for the first time ever in that country. Affirmative action represented a major step in Brazil’s process of democratization and nation-building, which ran against Brazil’s long-held ideology of racial democracy. Racial democracy was a belief since the 1930s that racism and racial discrimination were minimal or nonexistent in Brazilian society in contrast to the other multiracial societies in the world. By the 1990s, ideas of racial democracy were being slowly eroded as Brazil democratized and a small but active black movement denounced the popular idea of racial democracy, as it alleged that racism was widespread and pointed to official statistics showing Brazil’s tremendous racial inequality.

From the 16th through the 19th century, Brazil’s economy was based on agriculture and mining, which depended on a large African-origin slave population. During more than 300 years of slavery, Brazil was the world’s largest importer of African slaves, bringing in seven times as many African slaves to the country compared to the United States. In 1888, Brazil, with a mostly black and mixed-race or mulatto population, became the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery. Abolition in Brazil, though, did not create a rupture in the country’s racial inequality or its beliefs about black people.

Miscegenation and the fluidity of racial classification in Brazil throughout much of its history has largely been used as proof of its racial democracy. During slavery and colonialism, Brazil experienced greater miscegenation or race mixture than the United States, which resulted largely from a high sex ratio among its European settlers. In contrast to a family-based colonization in North America, Brazil’s Portuguese settlers were primarily male. As a result they often sought out African, indigenous and mulatto females as mates, and thus miscegenation or race mixture was common. Throughout its history, there were no anti-miscegenation laws like those found in the United States or South Africa. Today, Brazilians often pride themselves on their history of miscegenation and they continue to have rates of intermarriage that are far greater than those of the United States. Relatedly, there were no classification laws nor was there racially-based violence. The absence of classificatory laws and a high rate of miscegenation resulted in a racial continuum with racial categories from black to white and going through intermediate colors that shaded into each other. Thus, the racial classification of some Brazilians is ambiguous, at times varying according to the classifier and the social context.

photo credit: Ademir Rodrigues

Today, most Brazilians of all colors now acknowledge that there is racial prejudice and discrimination in their country, despite miscegenation and fluid racial classification. Based on statistical analysis of censuses and surveys along with other kinds of evidence, we know that racial inequality is high and racial discrimination in the labor market and other spheres of Brazilian society are common. Nonwhites are the major victims of human rights abuses, including that from widespread police violence. On average, black and brown (mulatto or mixed race) Brazilians earn half of the income of white Brazilians. Moreover, television and advertising portray Brazilan society as one that is almost entirely white, even though nearly half of the population identifies itself as nonwhite. Despite the historical and contemporary absence of race-based laws and Brazilians’ historical denial of racism, Brazilians are not surprised when others make racist jokes or a racist comment.

Most notably, the middle class and the elite is almost entirely white so that Brazil’s well-known melting pot only exists at the working class and poor levels. The near absence of Afro-Brazilians in the middle class is closely related to their poor representation in Brazilian universities. Nonwhite Brazilians were rarely found in Brazil’s top universities, until affirmative action began in 2001. Because of this, university admissions may be the most appropriate place for race-conscious affirmative action. By 2008, roughly 50 Brazilian universities have established some type of race-based affirmative action policy.

Affirmative action has also led to a commonplace discussion of race and racism in Brazil, for the first time, whereas the racial democracy ideology treated any talk of race as racist itself. There was little formal discussion of race in Brazilian society, while other societies were thought to be obsessed with race and racial difference. Only explicit manifestations of racism or race-based laws were viewed as discriminatory and thus only countries like South Africa and the United States were seen as truly racist.

Traditionally, Brazilian universities depended on a standardized test, known as the vestibular, as the only criteria for admission. Many leading universities are now mandated to admit a fixed percentage of nonwhite students while others use a point system that awards additional points to Afro-Brazilian students. Many of these universities also have quotas for indigenous people, for the disabled and those that attended the poorly funded public schools that the middle class tend to avoid, or award points based on these social disadvantages. Nevertheless, the focus of efforts to repeal affirmative action have been on the quotas for Afro-Brazilian students.

photo credit: Ademir Rodrigues

Affirmative action policies represent a new stage in Brazil’s effort to combat racial inequality and they are not without controversy as a backlash against them has been mounting. Detractors of these policies include much of the media, private school students, their parents and the schools themselves, scholars and artists who value the racial democracy ideal and even black students who believe in meritocracy. They claim, among other things, that class-based policies and universal reforms such as improved public education would have the same effect without having to define Brazilians on the basis of race or color, that affirmative action violates Brazilian principles of meritocracy and universalism, that affirmative action admits unqualified students to the university, that high levels of miscegenation often make it impossible to distinguish blacks from whites, that affirmative action divides Brazilians into black and white for the first time and thus will create racial hostility, and that poor whites continue to be excluded from university education. Furthermore, they claim that affirmative action is a U.S. import that is out of place in Brazil, even though affirmative action began in India in 1948 and has been used in several other countries. Legal challenges to university-based affirmative action are now before the Brazilian Supreme Court. A statute of racial equality, which would institutionalize affirmative action in all Brazilian universities as well as in public contracts and in public employment, passed the Brazilian senate and is now pending before the Chamber of Deputies, and has come under particular scrutiny by opponents of affirmative action.

Defenders of racial quotas continue to argue that race conscious remedies, together with universalist policies, are needed to significantly reduce Brazil’s high levels of racial and class inequality and that prior to affirmative action there was little concern for redressing racial inequality or even for reforming the poor state of public schools. The end of racial democracy thinking, a national debate about race and racism and the beginning of serious policy attempts to reduce racial inequality represent a new stage in Brazil. Brazil’s affirmative action experiment is still in its early stages and so far the concerns of its detractors have not been borne out as Afro-Brazilians often do as well or even better than the regularly admitted students, and race relations have not become hostile. At the same time, an unprecedented number of Afro-Brazilians have begun to graduate from top universities, which is certain to diversify Brazil’s middle class and create positive role models for Brazil’s large Afro-Brazilian population.

Edward E. Telles is a sociology professor at Princeton University and is the author of Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil, published by Princeton University Press in 2006.