Charlotte Mangin

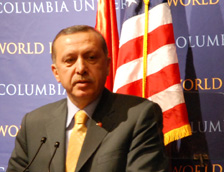

Yesterday, on a gray rainy New York afternoon, Columbia University’s World Leaders Forum hosted the prime minister of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, for his first public speech in the United States outside of the United Nations Security Council.

Security was tight, complete with metal detecting wands and bomb-sniffing dogs, as the 200-plus faculty and students filed into the packed venue. A motorcade of black SUVs with blaring sirens and flashing lights dropped off the guest of honor and some twenty other Turkish dignitaries.

The instant Prime Minister Erdogan appeared at the podium, flanked by secret police, a Kurdish activist student unfurled a handwritten banner reading “Turkey Out of Kurdistan” – and was promptly escorted out of the room by Columbia security. This small incident averted, Erdogan commenced his keynote address in Turkish, with a simultaneous interpreter translating into audience headsets.

In his opening remarks, Erdogan congratulated President-elect Barack Obama for his election victory, and expressed confidence in U.S.-Turkey solidarity under an Obama administration. “Leaders may change, governments may come and go, but relations between our countries will continue,” the Prime Minister affirmed.

He then turned to discussion of the global financial crisis – the reason for his present visit to America being this week’s G-20 meeting in Washington. Evoking the gravity of the present crisis with a stark image of global interdependency and the necessity for multilateral solutions, he said: “All countries are passengers on the same ship… If we sink, we will all go down together.”

Erdogan called upon the G-20 leaders to also turn their attentions to other “ticking timebombs” around the world that are at the top of Turkey’s foreign policy agenda: the unsettled border disputes between Turkey’s neighbors Russia and Georgia, and Armenia and Azerbaijan; achieving stability in Iraq, which the Prime Minister predicted could take “up to 10, 20, or even 30 years”; resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; and preventing Iran from developing weapons of mass destruction. Although critical of Iran’s nuclear program, Erdogan also pointed to the hypocrisy of America’s policies: “Nuclear weapons are being harbored in many countries,” he said. “Taking a stand against one country and forcing them to disarm is not an honest approach…. It needs to be across the board. Let’s eradicate these weapons once and for all.”

The speech comes just days after Erdogan officially volunteered to serve as mediator between Iran and the United States, in the aftermath of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s letter to Barack Obama. As both a member of NATO and a Muslim country, Turkey sees itself as uniquely placed to act as a bridge between the West and the Middle East.

Elaborating on this theme, Erdogan expressed continued ambition to join the European Union, and dismay that Turkey has yet to be accepted as a member state: “We are doing our homework and are further along than many of the 27 member countries.” Turkey has been working toward E.U. membership for over four decades, but is the first Muslim nation under consideration. Ending on a more upbeat note, the Prime Minister rejoiced that Turkey has been accepted to serve as a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for 2009 and 2010 – the first time in the U.N.’s 47-year history.

Erdogan concluded poetically: “We want to make new friends rather than enemies, and be a pro-active agent of peace…. We want to be a country that harvests not hatred but rather harvests, and therefore reaps, love.”

As the motorcade pulled away, audience members were overwhelmingly heartened by Erdogan’s message of peace and harmony, and his vision of Turkey’s growing role on the international stage. But a few skeptics pointed to a bumpy road ahead given the country’s position as a secular yet pious society, caught between the West and Islam.

WIDE ANGLE’s Turkey’s Tigers reported on the tensions between Islam and Western-style capitalism in Turkish business circles.