Major transit country for illegal labor en route to U.S. markets.

Type: Source and Transit Country

Background

Mexico serves primarily as a transit country for traffickers’ ultimate market — the U.S. Victims come mostly from Central America, though Brazil and Eastern Europe are also represented. The Mexican organized crime group Titanium runs one of the world’s largest slavery and forced labor rings, a recent study by Johns Hopkins University found. Mexican smugglers have also been subcontracted by Chinese trafficking rings to ship Chinese migrants over U.S. borders. With limited legal obstacles and widespread poverty, many Mexicans also become victims and are shipped to the U.S. Demand is highest for women and children, though men, as an investigative piece published by THE NEW YORKER in April 2003 revealed, are often shipped to fruit farms throughout the southern U.S. as well.

Victims

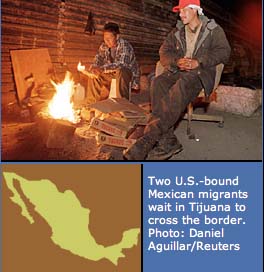

Migrants from Central America or residents of the Mexican highlands hoping to get work on farms or construction sites in the U.S. come to Mexico’s border towns in droves. Brought into the U.S. by “coyotes,” or smugglers, those that survive the crossing often find themselves at the mercy of a handler who delivers them to their ultimate work site. Unable to pay for transportation or food, upon arrival a work foreman allegedly pays for these services for them. Not speaking English (or, often, Spanish, in the case of victims from Mexico’s native population), they have little choice but to work off their so-called “debts” at the work boss’s bidding. Such practices have long been the focus of immigration officials in southern California and the border areas of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, but South Florida is also “ground zero for modern slavery,” a U.S. Justice Department official told THE NEW YORKER. Successful prosecutions remain few: In the past six years, six cases have been successfully prosecuted.

Nor do children escape from Mexico’s trafficking rings. As of 2001, according to UNICEF and the Mexican National System for Integration of the Family, an estimated 16,000 children were used for sexual exploitation within Mexico. Hondurans, Guatemalans, and El Salvadorans were also among those at work in the sex industry. Promising well-paying jobs, traffickers sell children to bar owners or to other traffickers, who then use the meals and lodging provided as a so-called debt that must be repaid. Some children are trained to operate in tourist centers such as Acapulco, Cancun, or Guadalajara. Others head to large border cities like Tijuana, Baja California, or Ciudad Juarez.

Counter-Trafficking Efforts

Though much publicity has been given to U.S. efforts to assist trafficking victims within American borders, in Mexico their chances for assistance are much less. One major obstacle is that trafficking per se is not illegal in Mexico. Instead, immigration, organized crime, and penal codes are used to prosecute suspected offenders. The government also makes no distinction between foreign traffickers and victims apprehended in raids: both are summarily deported, thereby clearing the way for the cycle of trafficking to begin again. Government officials and police themselves are often involved in smuggling rings, a study by Johns Hopkins University reported. Yet at the same time, Mexico has reportedly improved efforts to monitor its borders. Some 15,000 foreign nationals without papers and hundreds of smugglers were prevented from crossing into the U.S. in 2001, the U.S. State Department claims. A national outreach campaign against sexual exploitation of children and relevant training for Mexican police have also been introduced.

For its part, the U.S. last year introduced a T visa that allows victims of human trafficking from countries like Mexico to stay in the U.S. if they would face “unusual and severe harm” by returning to their own country. The Justice Department has also set up a hotline for forced laborers smuggled into the US with the hope that establishing contact with victims of trafficking or slavery will help ferret out the perpetrators.