Victims from Burma, Cambodia, and China supply a booming sex tourism industry.

Type: Source, Transit, and Destination Country

Background

For traffickers in Southeast Asia, Thailand is a land of opportunity. Trafficking in this tourist hotspot is a roughly $12 billion industry — a bigger cash earner than the country’s drug trade, according to the International Labor Organization. Simple economics drive the boom: In Thailand, per capita income is $6,900; in the surrounding states of Cambodia, Laos, and Burma that figure hovers in the $1,500 to $1,700 range. Inadequately funded law enforcement and relaxed visa regulations have traditionally guaranteed the traffickers’ trade. To keep the supply steady, Thai crime groups also collaborate with mafia syndicates from China, Russia, Japan, Burma, and elsewhere, Human Rights Watch reports. The Japanese yakuzas (mafia groups) in particular have a strong presence in Thailand.

Victims

Traffickers find fertile ground in Thailand’s rugged North, where economic change has wreaked havoc. Many of the tribal residents in this highlands region also do not have Thai citizenship — a fact that leaves them particularly vulnerable to trafficking. In one northern Thai region, Mae Sai, 70 percent of the 800 families there had sold a daughter into prostitution, delegates at the 2001 Second World Congress against Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children were told. Age preferences for hill women range from early teens to mid-30s; trafficked children often are taught to sniff “rubber cement” so that they will perform whatever task required without objection.

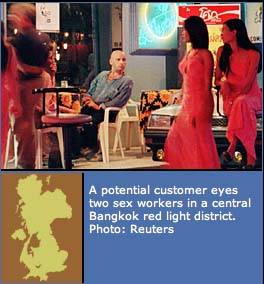

But with the boom in trafficked women and children from Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and China, demand for Thai women and girls is believed to have declined, THE BANGKOK POST recently reported. One fourth of Thailand’s estimated 200,000 commercial sex workers are believed to be Burmese, according to the paper.

But often, defining whether a victim has been forced to take up sex work or other labor or chosen to do so willingly is an impossible task. With limited options for work in Burma, Cambodia and Laos, the chance to go across the border to work on a “fruit farm” or other alleged business is a chance to earn money for a family’s clothes, food, education, and medicine. In Burma, ethnic Shan women are often rape targets for army troops — a claim denied by the ruling junta. “Being forced to work physically is one thing, but these women were forced to work by their situation,” Hseng Noung, of the Shan Women’s Action Network (SWAN), told THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR. “The women didn’t feel like they were rescued because they lost their money,” Noung said of one U.S.-funded anti-trafficking raid. “They felt like they were trapped.”

Counter-Trafficking Efforts

The scope of Thailand’s trafficking problem largely outstrips law enforcement resources, according to the 2003 Trafficking in Persons report. Last year, only half of the 42 people or organizations prosecuted for human trafficking received jail time. A $703,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Labor was extended in late 2002 to help the Thai government fight the trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation of girls in northern Thailand. Though legislation has been enacted to impose stiffer punishments on traffickers and offer greater support to victims, corruption within Thailand and lax efforts to address the problem by neighboring countries have resulted in an impasse.