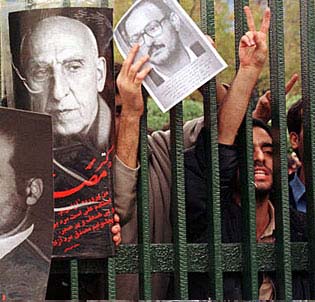

A newspaper kiosk burned by pro-Shah demonstrators in Tehran, Iran on August 19, 1953, during the coup attempt against Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq. Photo: Associated Press |

Following the long period of social and political stagnation of the nineteenth century, and the limited success of the forestalled constitutional movement of 1905-1911, the Pahlavi dynasty (1925-1979) was a transformative period in modern Iranian history. Taking advantage of the confusion of the post-WWI period (which was marked by economic crisis and British, Russian, and U.S. maneuvering over control of Iran’s oil supply) Reza Shah Pahlavi, an officer in Iran’s Russian-trained Cossack Brigade staged a military coup in 1921, abolished the ruling Qajar dynasty, and in 1925 declared himself the first shah of the new Pahlavi dynasty, after which he led Iran into an era of centralization, nation-building, and modernization from above. The Majles continued to convene, but the parliament’s power was subordinate to the centralized authority of the shah.

The reforms initiated under Reza Shah had profound implications for all areas of Iranian society, not least of which was the press and publishing industry. Emulating Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s nation-building efforts in the neighboring Republic of Turkey, Reza Shah seized upon the press and the publishing industry as a prime instrument for the dissemination of a new state-centered ideology of modernization. The Shah reined in the freedoms of the constitutional period, and obtaining a publishing license became a prerequisite for the establishment of a newspaper. Publishers lucky enough to obtain newspaper licenses were strictly observed, controlled, and often censored when they published anything critical of the state.

As a consequence, the number of newspapers in circulation declined between 1925 and 1941. The Tehran daily Ettela’at (Information) began publishing under the editorship of Abbas Masudi in 1925, and quickly become the most widely circulating newspaper in Iran, as well as becoming the semi-official voice of the government. Other forms of press control were also initiated. Fearing the spread of socialist ideas from the north and the threat of ethno-nationalist movements from within, the 1931 Press Law made it a crime to publish materials that were deemed unpatriotic or which advocated secession. In 1939 the new Ministry of Public Enlightenment was established with a mission to spread nationalist sentiment. The new ministry employed teams of writers who produced articles on ideologically approved topics, which were then channeled into newspapers and other periodicals throughout the country.

Official control of the media partially broke down between 1941 and 1953. Under pressure from the Allied powers during WWII, Reza Shah was forced to abdicate in favor of his young son Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, handing over power on September 16, 1941. The ensuing twelve years, between 1941 and 1953, proved to be a period of experimentation with democracy in Iranian society, much like the Constitutional Period of 1905-1911.

Unlike his authoritarian father, the new shah was weak, inexperienced, and had yet to consolidate his rule. During the ensuing period of political weakness on the part of the central government, the business of governing returned to the Majles, following the laws established during the constitutional period, which had remained on the books, and the media enjoyed a degree of openness and freedom that had been missing since Reza Shah took power. An avalanche of newspapers and printed materials expressing a stunning range of political points of view — from the pan-Iranist rightwing press to the official publications of the Iranian Communist Party — was published between 1941 and 1953.

In the context of this newfound freedom to organize and associate, political parties and other types of associations came to coalesce around particular newspapers, which in turn became the mouthpieces of particular social, cultural, and political points of view. The weak central government continued to try to censor and control the press, as did the Allied Occupation Forces (1941-1946), who closely monitored the press and reserved the right to suppress papers that published materials deemed derogatory to the interests of the occupation forces. Despite these official restrictions, however, by the late 1940s the Iranian press was deeply involved in a vigorous and often freewheeling public debate on the direction of Iranian politics.

The political consequence of this period of relative democratic openness was the rise of Mohammad Mossadeq to political prominence. As a longtime member of the Majles, and Prime Minister from 1951 to 1953, Mossadeq brought the oil issue to public prominence by sponsoring a bill in 1951 to nationalize the British controlled Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. The oil nationalization movement of 1951-1953 was made possible by the overwhelming public attention brought to the issue via discussions in the media. Mossadeq’s use of the print media — and the new medium of radio — was crucial in mobilizing popular support for the nationalization movement. The end of this crucial episode in modern Iranian history came with the overthrow of Mossadeq in August of 1953. Citing the growing threat of a communist takeover, the United States and Great Britain organized a clandestine operation code-named “Operation Ajax” to precipitate a military coup in Iran which would overthrow Mossadeq and bring Muhammad Reza Shah back to power.

The end of the Mossadeq era also meant the end of the era of relative openness in the media. After the overthrow of Mossadeq, Iran entered another period of protracted authoritarianism and state control of the media. During this period of royal dictatorship, between 1953 and 1978, political parties were outlawed, criticism of the monarchy was punished, and strict controls were placed on the content of newspapers, other printed materials, and the emerging mass media of radio, television, and film. The Ministry of Information and the Ministry of Culture became the main institutions controlling the content of such media, with enforcement in the hands of the much-feared Iranian secret police (SAVAK). As a consequence, throughout the 1950s and 1960s the number of Iranian newspapers once again declined as the reading public became skeptical of state-controlled content. The type of official content that came to permeate the press and other forms of media during this period included a steady stream of royalist and nationalist ideology, along with extensive coverage of official court ceremonies (salaams), the coronation of the Shah in 1967, and elaborate staged media spectacles such as the 2,500 year anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire, held to great official fanfare and media coverage in October of 1971.

- Previous: The Early Years

- Next: The Revolution and After