By Anwar Iqbal

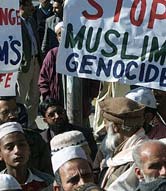

Pakistanis protesting the U.S.-led war against Iraq (Reuters/Mian Khursheed). |

Some fear that Pakistan is likely to become a Taliban-style state, run by hard-line mullahs, where rifle-toting bearded men will dominate the streets and women will be forced to don burqas.

The fear stems from the surprise gains of a six-party religious alliance called the United Action Council in the general elections held in October 2002. The alliance, better known by its Urdu acronym MMA, itself was a surprise because it included religious parties that had never previously been united.

What brought the religious parties together was the war in Afghanistan, with which Pakistan shares a long and porous border. The conflict had a major impact on both religious and secular forces in Pakistan.

The 1,000-mile-long stretch of land that divides the two countries includes the tribal belt, where many believe Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and his close aides are hiding. The fiercely independent Pathan tribes inhabit the region and pay little attention to the border set by the British in the early 20th century. Cross-border marriages are common, as are shared commercial interests and religious and tribal bonds.

Afghanistan’s former Taliban leaders were also Pathan, so when in the wake of 9/11 the United States began sending troops to Afghanistan, where bin Laden was living at the time, Pathan tribes in Pakistan sent thousands of volunteers to help the Taliban. When U.S. forces defeated the Taliban, who defied an ultimatum to turn over bin Laden as a measure to avoid war, in December 2001, the Pathan volunteers from Pakistan were trapped in Afghanistan. Many ended up killed and others were jailed.

When the federal government in Islamabad dumped its Taliban allies and joined the U.S.-led war against terror, many in the Pathan heartland saw this as an act of betrayal and treason. They were also unhappy with the liberal elements in Pakistani society — both Pathans and non-Pathans — who supported the United States. The Pathan nationalist parties, who had dominated all previous elections in their heartland, also isolated themselves by opposing the Taliban.

So in October 2002, when Pakistan held its first general elections three years after the military coup that brought army chief General Pervez Musharraf to power, Pathans decided to show their rejection of Islamabad’s policies by voting for the religious forces opposed to increasing U.S. influence in the nation. Religious parties also benefited from the absence of the country’s two main opposition party leaders — Nawaz Sharif of the Pakistan Muslim League (N) and Benazir Bhutto of the Pakistan People’s Party — who are both living in exile and prevented from participating in the elections by President Musharraf.

Consequently, the MMA emerged as the single largest political group in the Pathan areas. It now rules the North-West Frontier Province, where it has a majority in the provincial assembly, and also is a coalition partner in the adjacent Balochistan province. At the national level, the MMA won 53 seats in an assembly of 342, the highest number for any Islamist group since Pakistan’s creation in 1947. This makes the religious parties, who had never won more than 10 seats before this election, the third largest force in parliament after the pro-Musharraf ruling alliance and the opposition PPP of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.

A closer look at the election results, however, provides a better picture. The PPP, which won 62 seats in the National Assembly, received the highest number of votes, 25.01% of the total polled. The pro-Musharraf Pakistan Muslim League (PML-Q) received 24.81% of the votes. In the National Assembly, however, the PML-Q became the single largest party, with 77 seats, and later formed the federal government with the help of smaller parties.

The MMA, which surprised many by winning 53 seats, received 11.10% of the total votes. Even the smallest group in the National Assembly, the Pakistan Muslim League (N), the party of another former prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, got more votes. Although it has only 14 members in the assembly, it received 11.23% of the total votes.

This lends strength to the opposition’s claim that had its leaders — Bhutto and Sharif — been allowed to return from exile and campaign for their candidates, their parties might have fared better. It also strengthens the allegation by independent observers — including some from the European Union — that though the government did not interfere with the voting, it manipulated results to ensure that the PPP and PML (N) did not get a majority.

Although the MMA won 53 seats, it did not increase its vote bank. Religious parties usually receive 5% to 6% of all votes across the country. But because in the past they often competed against one another, their votes were split and they did not have a significant presence in the national legislature. There are also allegations the military government supported religious parties as a bulwark against the mainstream political elite and hopes to use the Islamic card in its dealings with the United States.

Whatever the reasons for the MMA’s victory in the October 2002 elections, it has boosted the alliance’s confidence. For the first time in Pakistan’s history, religious parties are talking of forming a government of their own rather than being content with a few seats in the federal or provincial cabinets. And since they do not have enough members in parliament to form a government, they have drawn out a long-term plan to reach that goal. They have already launched a two-pronged campaign to strengthen their position.

By opposing Musharraf and his pro-U.S. policies, the MMA hopes to cash in on anti-American feelings generated by the U.S.-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The group also wants to take advantage of the absence of Bhutto and Sharif to consolidate its position. The alliance leaders have demanded:

— the government withdraw laws promulgated by the military regime;

— Musharraf seek a vote of confidence from parliament and become a civilian president after shedding his uniform;

— the president give up power assumed through presidential decrees before the elections, such as the power to remove an elected government and dissolve parliament; and

— the National Security Council, which formalizes the military’s role in governance, be dissolved.

The MMA knows that neither the military nor the pro-military civilian government can accept these demands. But by whipping up these issues, it hopes to use them to expand its base of support in the next elections.

MMA leaders believe the present government, which is neither civilian nor military, will collapse sooner or later because of its built-in contradictions. They also believe that another U.S. action against a Muslim country — such as Iran — will further increase feelings of religious solidarity across the Islamic world, including Pakistan. And when it happens, they want to be ready to exploit the situation.

Anwar Iqbal is the South Asian Affairs Analyst for United Press International.