Since the founding of Pakistan as an Islamic state under the provisions of the Indian Independence Act of 1947, the nation has struggled between its Muslim heritage and the ideals of secular governance. Although the country’s first constitution, adopted in 1956, set up a parliamentary system of governance, military generals have ruled for the better part of its history. This timeline of Pakistan’s political history provides a framework in which to better understand the tensions at work in the nation today.

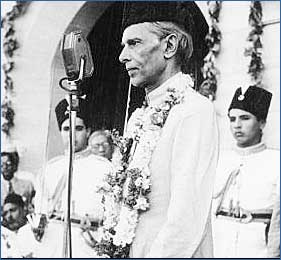

On August 14, 1947, the modern Islamic nation of Pakistan was created when India was partitioned after gaining independence following a century of British rule. The poet Muhammad Iqbal originally advanced the idea for a separate Muslim nation in 1930, and it became a reality under the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the head of the Muslim League, an organization formed to protect Muslim interests in India in the early 20th century. When Pakistan was created it consisted of two distinct regions, East and West Pakistan, that were 1,000 miles apart with only a shared religion in common. The eastern wing had the larger population, but political and military power rested in the western wing. Border issues still had to be resolved after partition — namely, how the provinces of Punjab and Bengal, which had substantial Muslim and Hindu populations, would be split, and which princely states would vote to join India or Pakistan. The announcement of the Punjab and Bengal boundaries a few days after partition resulted in one of the largest migrations of people in modern history — roughly six million Hindus and Sikhs fled to India while eight million Muslims fled to Pakistan. The chaotic population transfer was accompanied by unprecedented communal violence that left some 500,000 to 1 million people dead.

In Kashmir, where Muslims were the majority, the Hindu ruler wanted the state to become independent, but when armed Pathan insurgents infiltrated, he ceded Kashmir to India in October 1947. India and Pakistan went to war over control of the state, which only ended when a UN brokered cease-fire agreement was implemented in January 1949. A line of control divided Kashmir between the two nations, and although it was supposed to be a temporary solution, it is still in effect today.

Jinnah became the first governor general of an independent Pakistan, with Liaquat Ali Khan as the nation’s first prime minister. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the country’s founder and guiding force, died on September 11, 1948.

Liaquat Ali Khan, Jinnah’s close associate, remained prime minister after his death. Although Khan attempted to frame a constitution, wrangling over issues such as Islam’s role in the state and the power of the central government vis-à-vis the provinces continued; then, in 1951, he was assassinated. As a result, the nation was still governed by British colonial law (the 1935 Government of India Act) and witnessed a succession of prime ministers (six between 1951 to 1958) who, given the sustained regional and ethnic disputes, especially between East and West Pakistan, were unable to maintain a legislative majority in the Constituent Assembly (the central authority) and ensure that democracy took root, even following the adoption of the nation’s first constitution in 1956. It established Pakistan as an Islamic republic with a parliamentary system of government comprised of two administrative units, which had been set up in 1955 — West Pakistan, formed by the merger of its four provinces, and East Pakistan; installed a central authority, now called the National Assembly; and included directives on creating a state that followed Islamic tenets. Iskander Mirza became the country’s first president. However, the preceding years of political instability and corruption, compounded by an economic downturn in the mid-1950s, resulted in a military takeover of the state in 1958.

1958 – 1969: Military Dictatorship

In October 1958, President Iskander Mirza nullified the 1956 constitution and declared martial law, but within the same month he was toppled in a bloodless coup by the army commander-in-chief, General Ayub Khan, who then assumed the presidency. In the first years of martial law, he purged the government of corrupt politicians, instituted land reforms, and introduced a new system of government (Basic Democracies) — a multitiered plan of elected and government-nominated officials, with villagers electing members to a local council, which then elected members to the next tier, and so on until the highest tier, a provincial council. Using this system, General Ayub Khan won another five-year term as president in 1960 and the right to engineer a new constitution.

Martial law ended with the enactment of this new constitution in 1962. It created a presidential form of government, with the chief executive vested with vast powers, and a national legislature (the National Assembly) of 156 members. The president was the head of state (the Islamic Republic of Pakistan) and the government as well as the commander of the armed forces, and had the right to dissolve the National Assembly and veto legislation that it had passed by a two-thirds majority. The ban on political parties was removed later in the year.

Discontent with the military regime grew steadily after the 1965 war with India over Kashmir, as did agitation for more democracy. In the wake of civil unrest in East Pakistan, where the main political party (the Awami League) was calling for autonomy, General Ayub Khan resigned and handed power over to General Yahya Khan, the head of the Pakistani army, on March 25, 1969. He declared martial law and scheduled elections for 1970.

1970 -1977: Civil War/The Bhutto Years

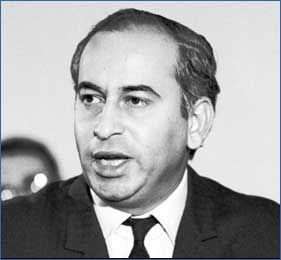

The first nationwide general election since independence was held in December 1970. The Awami League gained control of the National Assembly by winning nearly all the seats in East Pakistan, with the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, winning the majority of seats in West Pakistan. When negotiations between the two parties on the goals and constitution of the new government broke down at the end of March, East Pakistan declared its independence. Civil war erupted, with troops from West Pakistan battling irregular forces in East Pakistan and brutally suppressing the civilian population. India sent troops in aid of East Pakistan in early December 1971, and within two weeks West Pakistan’s troops surrendered; East Pakistan became the independent nation of Bangladesh.

Yahya Khan resigned and Bhutto became president and chief martial law administrator of a much smaller Pakistan. Under his leadership, banks, insurance firms, and major industries were nationalized, land reforms were instituted, and martial law lifted. In August 1973, a new constitution that the Bhutto government helped draft and that the National Assembly passed went into effect. The third constitution in the nation’s history, it set up a parliamentary system of government, and Bhutto resigned from the presidency to become prime minister. When his party, the PPP, won the March 1977 general elections, the opposition parties charged fraud and electoral malfeasance and began widespread demonstrations that turned violent. The army was called in to restore order.

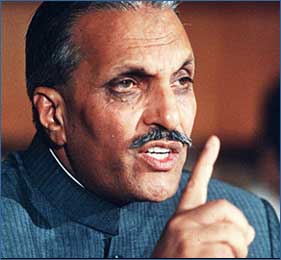

General Muhammad Zia ul-Haq, the chief of army staff, deposed Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in a bloodless military coup on July 5, 1977. General Zia declared martial law and continually promised to hold elections but kept canceling them over the next few years, finally banning political parties and suspending voting indefinitely by late 1979. By then, Zia had named himself president and removed his main political rival, Bhutto, who was jailed and convicted on dubious charges of conspiracy to murder an opposition leader, and hanged in April 1979.

One of the hallmarks of General Zia’s regime was the institution of legal codes that conformed to Islamic law and the establishment of the Federal Shariat Court. Under the hudud ordinances of these laws, which are still in effect today, rape and adultery are capital offenses, theft may result in the amputation of hands or feet, and flogging is prescribed for drunkenness or political crimes. Except for flogging, the draconian punishments have not been meted out or have been reduced on appeal. Interest-free banking and an alms tax were also instituted.

A nonparty general election was finally held in 1985, and subsequently, Zia exacted changes to the constitution (Eighth Amendment), giving greater power to the president and exempting his military regime from future prosecution; martial law was lifted in December 1985 and the amended constitution took effect. General Zia dismissed the parliament in mid-1988 and called for new elections in November of that year, but was killed in a plane crash on August 17, 1988.

1988 – 1996: Return to Democracy

Elections were held in November as scheduled and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), led by Benazir Bhutto, who had returned to Pakistan from exile in 1986, won the most seats in parliament; it formed a coalition government with the Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) and other smaller parties. Bhutto was sworn in as prime minister in December 1988. During her brief tenure, totaling 20 months, she was unable to pass any new legislation, given her party’s slender majority in the National Assembly. Her term was marked by increased ethnic violence in her home province of Sindh; strong political opposition from her main rival, Nawaz Sharif, Punjab’s chief minister; and charges of corruption brought against her allies and her husband. In August 1990, President Ghulam Ishaq Khan, under the provisions of the Eighth Amendment, dismissed the Bhutto government.

New elections held in October 1990 gave a resounding victory to a multiparty coalition (the Islamic Democratic Alliance), headed by the Pakistan Muslim League (PML), that also included religious right parties. The alliance gained control of the National Assembly as well as the provincial legislatures, with the support of other parties, and elected the head of the PML, Nawaz Sharif, as prime minister. Sharif implemented policies that stimulated economic growth through privatization, foreign investment, deregulation, and denationalization of industries. However, disputes between the PML and the other parties weakened the coalition, and tensions between the president and Sharif led to the dismissal of his government in 1993. Although Sharif fought the dismissal and won in court, he and President Khan could not resolve their differences and under pressure from the army, both resigned their posts.

Following a brief interim government, Benazir Bhutto returned as prime minister after the October 1993 elections, but again, amid charges of corruption, nepotism, and mismanagement, her government was dismissed in late 1996.

1997 – present: Pakistan Today

Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s party, the Pakistan Muslim League, won a decisive victory in the February 1997 elections that returned him to a second term. He quickly gained the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which gave the prime minister the authority to appoint the armed forces chiefs and repealed the Eighth Amendment that allowed the president to dismiss the prime minister and dissolve the National Assembly.

A renewed confrontation with India over Kashmir in mid-1999 ended with the withdrawal of Pakistani-backed troops from Indian-held Kashmir, which was widely resented by the civilian population and the armed forces. When Prime Minister Sharif attempted to dismiss the chief of the army, General Pervez Musharraf, the army ousted the civilian government in a bloodless coup on October 12, 1999.

Within a few days, General Musharraf declared a state of emergency, suspended the constitution and the federal and provincial assemblies, and made himself the chief executive. In May 2000, the Supreme Court validated the coup and stipulated that new elections should be held within three years. Prior to the scheduled October 2002 elections, General Musharraf removed the sitting president and took over the office in June 2001; held an unopposed national referendum that allowed him to continue as president for another five years at the end of April 2002; and in August 2002 amended the constitution to once again grant the president the power to dissolve the National Assembly. Although General Musharraf’s party, the Pakistan Muslim League (QA), won the most seats in the National Assembly, the October elections were noted for the success of a coalition of religious parties that made surprising gains nationally and won majorities in two provincial assemblies — North-West Frontier Province and Balochistan.