By Dorinda Elliott

July 18, 2002

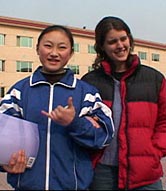

Li Xiu Ying (pictured with her former teacher) now attends an elite prep school thanks to a WIDE ANGLE viewer who donated the tuition costs. |

Along the neon-lined streets of Shanghai and Beijing, it’s clear that China is hurling itself into the global economy. Starbucks, Häagen-Dazs, and Chanel outlets are cropping up everywhere, and chichi eateries are jammed with hip young Chinese working for the new private economy.

Say this about China: it’s got the blind pursuit of money thing down pat, but the systems and values that normally accompany modernization — rule of law, transparency, civil society — are another matter. If political reform and democratization come to China on the tail of its new economic freedoms, the transition could be years in the making.

Government leaders make arbitrary decisions behind closed doors. Most Chinese still have little sense of their rights or social responsibilities. After all, 25 years ago China was stumbling out of the Cultural Revolution, a decade of political violence that tore families apart, shattered traditional values and ethics, and reinforced an animalistic survival instinct. That cataclysm opened the door for Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping to launch the nation on the path toward capitalism. Now, China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, which requires Beijing to open its markets and follow transparent, standardized trading practices, promises to accelerate the country’s transformation.

In the Gansu province in the far West , Mr. Chen, who makes a living driving a taxi, takes a sober view of the transition. Chen (he declines to give his full name) used to work at a state grain bureau until authorities suddenly announced that, like almost everything else in post-socialist China, it had to make a profit. To achieve that, Chen’s boss started secretly selling grain that was supposed to be stockpiled in case of famine or earthquake or nuclear disaster. The scandal was exposed, and the boss is now in prison. Chen lost his job. “You can’t make a profit being a grain bureau,” he says of his ex-boss, “so he did what he had to.”

Chen watched his boss pursue profits without any concern for legalities. But then, after more than 50 years of one-party rule, legalities in China can be a relative concept.

“There are no rules in China — none,” says Albert Louie, managing director of Beijing-based risk management consultants Albert William & Associates. “If the government wants you dead, they can always do it. This is their home turf.”

Beijing’s leaders know that both the government and the economy must open up and run more professionally for China to compete on the world stage. But the Chinese government hopes to use WTO to push economic reforms without blowing up the political system or threatening the Communist Party’s power. The government has sanctioned some very limited village elections. But at the central level, a gray group of bureaucrats is unlikely to relinquish tight control over government soon. Though economic reforms are giving people much more control over their daily lives, Beijing still outlaws any organized opposition.

Eager to maintain the political status quo, the government is realizing that it must handle the economic hardship that ensues from WTO gingerly. To help prepare the public for WTO, the government has organized a mass education campaign. Beijing cab drivers recite chapter and verse the pros and cons of joining the trade organization. Entrepreneurs, once banned from the party, can now apply for membership. Labor Medals, an honor once bestowed only on state sector workers, were presented by the All China Federation of Trade Unions to private businessmen in May 2002.

1949 China revokes its membership in the WTO’s predecessor, the GATT, calling it “a capitalist club.”

1978 China begins market-oriented reforms that give it one of the world’s fastest growing economies.

2000 China ranks as the world’s second largest economy after the U.S., based on purchasing power parity.

2001 After a 15-year membership campaign, China joins the WTO on December 15.

2003 Hu Jintao, the head of the fourth generation of leaders of the ruling Communist Party is elected to replace Jiang Zemin as President of China.

But is it enough?

“WTO changes everything,” says Wang Shan, a Beijing-based political economist. “Once you open up to the outside like this, transparency and competition will bring political change, too.” More transparent business practices will help wipe out the corruption that is eroding the country’s economy. Connections will matter less. As they are exposed to the outside world and modern practices, young Chinese already view the government with cynicism. What’s more, citizens are already fighting the government on issues ranging from housing to the environment. Eventually, they likely will demand better leaders, too.

One region to watch: China’s so-called “Rust Belt.” In the northeastern province of Liaoning, unemployed factory workers are so enraged by their poor treatment that they have dared to challenge authority and take to the streets in protest. When the protests grew to the tens of thousands in March, the government arrested three labor leaders, who, as of June 2002, still remain in prison. From Gansu to Sichuan and the industrial Northeast, workers already regularly protest, demanding back pay and proper compensation. It’s hard to say how far such demonstrations will go, but labor unrest is one of Beijing’s greatest fears.

Still, the connection between inept managers at state-run companies and the government in Beijing that put them there is not always made.

Remarkably, Chen, the driver, doesn’t blame his old boss for the fact that Chen lost his job. “It really wasn’t his fault,” he says with a shrug. “He was just a guinea pig for reforms. We are all guinea pigs.”

— Dorinda Elliott was editor of ASIAWEEK magazine and has covered China for the last 20 years. She is now an editor-at-large at Time Inc.