Is Russia returning to a Soviet-era repression of the media?

by Richard Pipes

July 5, 2004

When the Communists were in power, we had no way of knowing what ordinary Russians thought because all the media, without exception, were controlled by the Communist Party and expressed its interests. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the situation in this respect has undergone drastic change. Russians have adopted with great enthusiasm western methods of public opinion polling and we now have reliable information about their thoughts and wants on almost every subject. The leading polling organization is the All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion, directed by Iurii Levada. The results from this and other such institutes are regularly reported in their own publications as well as in the popular daily, IZVESTIA. The information provided below dates from 1999-2004.

Unfortunately, the results of these polls are not encouraging.They indicate a preference for order over freedom, suspicion of democracy and the free market, and nostalgia for the Soviet Union. Russians emerge as a people who mistrust everyone except their closest family and friends, as individuals who, in the words of one opinion survey, live in “trenches” feeling surrounded on all sides by enemies.

Such attitudes have at least three causes. One is the age-old tradition of autocratic government which gave Russian citizens no voice in affairs of state and forced them to rely on their own efforts to survive in a harsh climatic environment. Another is the disappointment which Russians have experienced when the expectations they had of democracy and capitalism after the collapse of communism did not immediately bring them stability and prosperity. And the third are the actions of the country’s powerful president, Vladimir Putin, who has contempt for democratic procedures and is reverting Russia to a one-party state, promoting political apathy.

As a consequence of these factors, today’s Russians view democracy as a fraud: 78 percent of respondents in a 2003 survey said that democracy is a facade concealing a regime in which real power is exercised by rich and powerful cliques. Only 22 percent express a preference for democracy, whereas 53 percent positively dislike it. 52 percent believe multiparty elections do more harm than good. Altogether Russians feel they have no influence over government, whether national or local, and hence are quite prepared to live under a one-party regime.

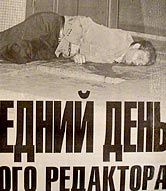

Mourners carry a coffin containing the body of murdered journalist and TOGLIATTI OBSERVER editor Valery Ivanov. |

They attach little importance to liberties. Only one in ten Russians would be unwilling to surrender the freedom of speech, press, or movement in exchange for “order” or “stability.” A recent poll brought out the stunning fact that fully three-quarters of Russians want the restoration of censorship on the mass media. The reason seems to be that they are disturbed by unsettling news as well as by the impropriety of some of the spectacles presented on television.

Russians hold the judiciary system in contempt, believing that the courts are thoroughly corrupt. They refer to court proceedings as auctions in which the highest bidder wins out. Businesses prefer to resort to arbitration. Others resort to the mafia. Many of the non-political murders which occur in Russia (and whose culprits are never caught) are the result of this kind of private “justice.”

Nor are Russians more positive about capitalism. 84 percent of respondents of a poll published in January 2004 asserted that in their country wealth could be acquired only by illegal means, mainly by exploiting the right connections. They want the state to be much more involved in directing the nation’s economy. They attach little value to private property, which only a quarter or so regard as a basic human right. Slightly more than half the population considers nonpayment of debts or shoplifting to be “fully acceptable behavior.” They prefer financial security to wealth: 6 percent are prepared to accept the risks attendant on private enterprise, whereas 60 percent would opt for a small but assured income.

They pine for the great power status which Russia enjoyed during Soviet days. When asked to list the greatest men in history they rank them, in this order, Peter I, Lenin and Stalin, who have in common that they enhanced Russia’s place in the world. When asked how they would like their country to be perceived by other nations, 48 percent of Russians says “mighty, invincible, indestructible, a great world power.” 22 percent want it perceived as “affluent and thriving” and a mere 1 percent as “law-abiding and democratic.” These findings help explain why 74 percent of respondents in one poll regret the passing of the Soviet Union. Asked how they would react if the Communists seized power as Lenin had done in October 1917, 23 percent of respondents say they would actively support it, 19 percent would collaborate with it, 27 percent would do their best to survive, 16 percent would emigrate, and only 10 percent would actively resist.

Family members gaze at the lifeless body of Alexei Sidorov, the second editor of the TOGLIATTI OBSERVER, who assumed his role after the murder of Ivanov. |

These results do not bode well for Russia’s future as a democracy and a member of the international community. But it must be borne in mind that they are not due to some genetic predisposition of Russians for autocratic government. Rather, they can be explained in terms of their historical experience. Throughout the 700 years of its existence as an organized state, Russia has had to administer too vast a territory with too limited resources to indulge in democracy such as is possible in small and wealthy countries. It relied on the police and bureaucracy. The population at large, alienated from the state which extracted manpower and taxes but gave nothing in return, relied mainly on its own resources. It became exceedingly privatized, lacking in the sense of social and political belonging. Because Russians do not trust each other, they rely on a powerful, authoritarian state to protect them from each other. The Communist regime, during its 70 year reign, reinforced these traditional attitudes.

If Russia is given several decades of peace and stability, it may well develop different attitudes. “Order” and “freedom” then will not appear as alternatives but as complimentary values. People will want to have a voice in how their government is run, and come to rely on law. But this will take time.

Richard Pipes is Professor of History, Emeritus, at Harvard University. He is the author of numerous books on Russian history, including RUSSIA UNDER THE OLD REGIME and THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION. His most recent publication, published by Yale University Press, is VIXI: THE MEMOIRS OF A NON-BELONGER.