To what extent can Congo’s current problems be traced back to the legacy of Mobutu Sese Seko’s rule? Africa correspondent Michela Wrong offers some insight in this introduction to her book about the rise and fall of the man also known as The Leopard.

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF MR. KURTZ

Michela Wrong

Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins ©2000

The feeling struck home within seconds of disembarking.

When the motor-launch deposited me in the cacophony of the quayside, engine churning mats of water hyacinth as it turned to head back across the brown expanse of oily water that was the River Zaire, I was hit by the sensation that so unnerves first-time visitors to Africa. It is that revelatory moment when white, middle-class Westerners finally understand what the rest of humanity has always known — that there are places in this world where the safety net they have spent so much of their lives erecting is suddenly whipped away, where the right accent, right education, health insurance and a foreign passport — all the trappings of “It Can’t Happen to Me” — no longer apply, and their well-being depends on the condescension of strangers.

The pulse of apprehension drummed as I stuffed my clothes back into the ageing suitcase that had chosen the river crossing between Brazzaville and Kinshasa as the moment to split at the seams, transforming me into a truly African traveler. It quickened as a sweating young British diplomat signally failed to talk our way through the red tape and a chain of hostile policemen picked through the intimacies of my luggage, deciding which bits to keep. It subsided as we emerged from our three-hour ordeal, a little the lighter, finally crossing the magic line separating the customs area from the city.

But in truth, the quiet thud of fear would be there throughout my time in Zaire, whether I was drinking a cold Primus beer in the bustling Cité or taking tea in the green calm of a notable’s patio. This ominous awareness of a world of infinite, sinister possibilities has become one of the dominant characteristics of the nation led by the man who started life as plain Joseph Désiré Mobutu, cook’s son, but reinvented himself as Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga, “the all-powerful warrior who goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake.”

By the end of the mid-1990s, Mobutu had become more noticeable by his absence than by his presence, a tall, gravel-voiced figure glimpsed occasionally at official ceremonies and airport walkabouts in Kinshasa, or fielding hostile questions at a rare press conference in France with a sardonic politeness that hinted at huge world-weariness. Rattled by the army riots that had twice devastated his cities, belatedly registering the extent to which he was hated, he had withdrawn from a resentful capital to the safety of Gbadolite, his palace in the depths of the equatorial forest, to nurse his paranoia.

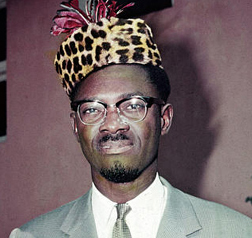

His impassive portrait, decked in comic-opera uniform, kept watch on his behalf, glowering from banks, shops and reception halls. “Big Man” rule had been encapsulated in one timeless brand: leopardskin toque, Buddy Holly glasses and the carved cane so imbued with presidential force mere mortals, it was said, could never hope to lift it. He liked to be known as the Leopard, and the face of a roaring big cat was printed on banknotes, ashtrays and official letter-heads. But to a population that had once hailed him as “Papa,” he was now known as “the dinosaur,” a tribute to how sclerotic his regime had become. Certainly, on a continent of dinosaur leaders, of Biya and Bongo, Mugabe and Moi, he rated as a Tryrannosaurus Rex of the breed, setting an example not to be followed. No other African autocrat had proved such a wily survivor. No other president had been presented with a country of such potential, yet achieved so little. No other leader had plundered his economy so effectively or lived the high life to such excess.

Preyed on by young men with Kalashnikovs, its administration corroded by corruption, a nation the size of Western Europe had fallen off the map of acceptable destinations. My battered copy of the Belgian Guide Nagel, picked up in a Paris bookshop, described Kinshasa as a modern capital “boasting all the usual attributes of Europe’s great cities” and encouraged the tourist to explore its museums, monuments and “indigenous quarters.” But that had been in 1959, when the world was a white man’s oyster. Kinshasa was now a stop bypassed by hardened travelers, where airlines avoided leaving their planes overnight for fear of what the darkness would bring. A hardship posting for diplomats, boycotted by the World Bank and IMF, it was a country every resident seemed determined to abandon, if only they could lay their hands on the necessary visa.

I would be there for the end, and for the beginning of the end.

Less than three years after my arrival, the tables were turned and I was the one to experience the curious intimacy the looter shares with his victim, rifling through Mobutu’s wardrobes, touring his bathroom and making rude remarks about the taste of his furniture (“African dictator” kitsch of the worst kind). Somewhere at the back of one of my drawers, there is a stolen fishknife that was once part of the presidential dining set. My companions in crime were more ambitious — they took monogrammed pillow cases, bottles of fine French wine, even a presidential oil portrait. But looters were being shot on the streets the day we paid our unannounced visit on Marshal Mobutu’s villa in Goma, and I wasn’t going to risk execution for a souvenir.

It was November 1996 and the new rebel movement that had suddenly risen from nowhere in the far east of Zaire had seized control of the area bordering Rwanda. For weeks the frontier crossings leading into this breathtakingly beautiful region of brooding volcanoes and misty green valleys, all rolling down to the blue waters of Lake Kivu, had been closed while the fighting went on. Then suddenly the victorious rebels opened the frontier, and a small flood of journalists who had been kicking their heels on the other side poured across.

When the tour agencies were still brave enough to include Rwanda and Zaire in their African itineraries, Goma was a favorite destination for tourists visiting some of the world’s last mountain gorillas. A pretty little town on the black lava foothills, it had now been torn apart by its own inhabitants, who had taken the army’s exodus as the cue for some frenzied self-enrichment. Shops had been eviscerated, the main street was a mess of phone directories, glass and unused condoms, shattered toilet bowls and broken shutters. “They’ve attacked me four or five times, but they just won’t believe I don’t have anything left to take,” gasped a ruined Lebanese trader, waiting at the border post for permission to leave. His eyes were swimming with tears.

The atmosphere was prickly. Starting what was to prove a seven-month looting and raping retreat across the country, Zairean forces had lashed out indiscriminately before pulling out, leaving corpses scattered for kilometers. No one was too sure of the identity of the rebel movement, the new bosses in town. And then there were the roaming Rwandans, whose intervention in Zaire was being denied by the government next door but was too prominent to ignore. Speaking from the corner of his mouth, a resident confirmed the outsiders’ presence: “We recognize them by their morphology.” Then he hurried away as a baby-faced Rwandan soldier — high on something and all the more sinister for the bright pink lipstick he was wearing — swaggered up to silence the blabbermouth.

Somehow, Mobutu’s villa seemed the natural place to go. The road ran along the lake, snaking past walls draped in bougainvillaea, with the odd glimpse of blue water behind. We surprised a lone looter who had decided, enterprisingly, to focus on the isolated villas of the local dignitaries, rather than the overworked town center. Thinking we were rebels, he stopped pushing a wheelbarrow on which a deep freeze was precariously balanced and ran for cover. As we drove harmlessly by, he was already returning to his task. A stolen photocopier and computer were still waiting to be taken to what, almost certainly, was a shack without electricity.

In the old days, the villa complex had been strictly off limits behind staunch metal gates manned by members of the presidential guard. Now the gates were wide open and the Zairean flag — a black fist clenching a flaming torch — lay crumpled on the ground. There had been no fight for this most symbolic of targets. No one, it was clear from the boxes of unused ammunition, the anti-tank rockets and mortar bombs carelessly stacked in the guards’ quarters, had had the heart for a real showdown.

In the garage were five black Mercedes, in pristine condition, two ambulances, in case the president fell sick and a Land Rover with a podium attachment to follow him, Pope-like, to address the public. A generous allocation for a man whose visits had become increasingly rare. But like a Renaissance monarch who expected a bedroom to be provided in any of his baron’s castles, Mobutu kept a dozen such mansions constantly at the ready across the country, on the off-chance of a visit that usually never came.

It was on the verge of venturing inside — could the property possibly be tripwired? — that we really began to feel like naughty children sneaking a look in their parents’ bedroom, only to emerge with their illusions shattered. From outside the villa had looked the height of ostentatious luxury; all chandeliers, Ming vases, antique furniture and marble floors. Close up, almost everything proved to be fake. The vases were modern imitations, they came with price labels still attached. The Romanesque plinths were in molded plastic, the malachite inlay painted on.

With an “aha!” of excitement, a colleague whipped out a black and white cravat, of the type worn with the collarless “abacost” jacket that constituted Mobutu’s eccentric contribution to the world of fashion. From a distance, the cravats had always appeared complex arrangements of material, folded with meticulous care. Now I saw they were little more than nylon bibs, held in place with tabs of Velcro. This emperor did have some clothes. But like his regime itself, they were all show and no substance.

Most poignant of all, perhaps, was the pink and burgundy suite prepared for the presidential spouse, although it was impossible to say whether this was the first lady Bobi Ladawa, or the twin sister Mobutu had, bizarrely, also taken to his bed. An outsize bottle of the perfume Je Reviens, which had probably turned rancid years ago in the African heat, stood on the mantelpiece. With their man ravaged by prostate cancer, his shambolic army collapsing like a house of cards, neither woman would ever be returning to Goma. This irreverent plundering was the only proof required of how rapidly the power established over three decades was unraveling.

Rebel uprisings, bodies rotting in the sun, a sickening megalomaniac. In newsrooms across the globe, shaking their heads over yet another unfathomable African crisis, producers and sub-editors dusted off memories of school literature courses and reached for the clichés. Zaire was Joseph Conrad’s original “Heart of Darkness,” they reminded the public. How prophetic the cry of despair voiced by the dying Mr. Kurtz at Africa’s seemingly boundless capacity for bedlam and brutality had proved yet again. “The horror, the horror.” Was nothing more promising to ever to emerge from the benighted continent?

Yet when Conrad wrote HEART OF DARKNESS and penned some of the most famous last words in literary history, this was very far from his intended message. The “Heart of Darkness” itself and the phrase “the horror, the horror” uttered by Mr. Kurtz as he expires on a steam boat chugging down the giant Congo river, probably constitute one of the great misquotations of all time.

For Conrad, the Polish seaman who was to become one of Britain’s greatest novelists, HEART OF DARKNESS was a book based on some very painful personal experiences. In 1890 he had set out for the Congo Free State, the African colony then owned by Belgium’s King Leopold II, to fill in for a steamship captain slain by tribesmen. The posting, which was originally meant to last three years but was curtailed after less than six months, was to be the most traumatic of his life. It took him nine years to digest and turn into print. Bouts of fever and dysentery nearly killed him; his health never subsequently recovered. Always melancholic, he spent much of the time plunged into deep depression, so disgusted by his fellow whites he avoided almost all human contact. His vision of humanity was to be permanently colored by what he found in the Congo, where declarations of philanthropy camouflaged a colonial system of unparalleled cruelty. Before the Congo, Conrad once said, “I was a perfect animal”; afterwards, “I see everything with such despondency — all in black.”

Mr. Kurtz, whose personality haunts the book although he says almost nothing, is first presented as the best station manager of the Congo, a man of refinement and education, who can thrill crowds with his idealism and is destined for great things inside the anonymous Company “developing” the region. Stationed 200 miles in the interior, he has now fallen sick, and a band of colleagues sets out to rescue him.

Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Republic of Congo, on July 3, 1960. Lumumba was later assassinated in January 1961. |

When they find him, they discover that the respected Mr. Kurtz has “gone native.” In fact, he has gone worse than native. Cut off from the Western world, inventing his own moral code and rendered almost insane by the solitude of the primeval forest, he has indulged in “abominable satisfactions,” presided “at certain midnight dances ending with unspeakable rites” says Conrad, hinting that Kurtz has become a cannibal.

His palisade is decorated by rows of severed black heads; he has been adopted as honorary chief by a tribe whose warriors he leads on bloody village raids in search of ivory. The man who once wrote lofty reports calling for enlightenment of the native now has a simpler recommendation: “Exterminate all the brutes!” When he expires before the steamer reaches civilization, corroded by fever and knowledge of his own evil, his colleagues are relieved rather than sorry — a potential embarrassment has been avoided.

Despite its slimness, the novella is one of those multilayered works whose meaning seems to shift with each new reading. By the time HEART OF DARKNESS was published in 1902, the atrocities being committed by Leopold’s agents in the Congo were already familiar to the public, thanks to the campaigns being waged by human rights activists of the day. So while HEART OF DARKNESS is in part a psychological thriller about what makes man human, it had enough topical detail in order to carry another message with it to its readers. Notwithstanding the jarringly racist observations by the narrator Marlow, the way HEART OF DARKNESS dwells on the sense of utter alienation felt by the white man in the gloom of central Africa, the book was intended primarily as a withering attack on the hypocrisy of contemporary colonial behavior. “The criminality of inefficiency and pure selfishness when tackling the civilizing work in Africa is a justifiable idea,” the writer told his publisher.

So, when Kurtz raves against “the horror, the horror,” he is, Marlow makes clear, registering in a final lucid moment just how far he has fallen from grace. The “darkness” of the book’s title refers to the monstrous passions at the core of the human soul, lying ready to emerge when man’s better instincts are suspended, rather than a continent’s supposed predisposition to violence. Conrad was more preoccupied with rotten Western values, the white man’s inhumanity to the black man, than, as it is almost always assumed today, black savagery.

Why then, nearly a century on, has the phrase, and the title, become so misunderstood, so twisted?

The shift reflects, perhaps, the level of Western unease over Africa, a continent that has never disappointed in its capacity to disappoint: Hutu mothers killing their children by Tutsi fathers in Rwanda; the self-styled Emperor Bokassa ordering the cook to serve up his victims’ bodies in Central African Republic; Liberia’s rebels gleefully videotaping the torture of a former president — the terrible scenes swamp the thin trickle of good news, challenging the very notion of progress.

On a disturbing continent, no country, appropriately enough, remains more unsettling than the very birthplace of Conrad’s masterpiece: the nation that was once called the Congo Free State, later metamorphosed into Zaire and has now been rebaptized the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In Mobutu’s hands, the country had become a paradigm of all that was wrong with post-colonial Africa. A vacuum at the heart of the continent delineated by the national frontiers of nine neighboring countries, it was a parody of a functioning state. Here, the anarchy and absurdity that simmered in so many other sub-Saharan nations were taken to their logical extremes. For those, like myself, curious to know what transpired when the normal rules of society were suspended, the purity appealed almost as much as it appalled. Why bother with pale imitations, diluted versions, after all, when you could drench yourself in the essence, the original?

The longer I stayed, the more fascinated I became with the man hailed as the inventor of the modern kleptocracy, or government by theft. His personal fortune was said to be so immense, he could personally wipe out the country’s foreign debt. He chose not to, preferring to banquet in his palaces and jet off to properties in Europe, while his citizens’ average annual income had fallen below $120, leaving them dependent on their own wits to survive. What could be the rationale behind such callous greed?

Zaireans had demonized him, seeing his malevolent hand behind every misfortune. From mass murder to torture, poisoning to rape — there were few crimes not attributed to him. But if Mobutu has approached near-Satanic proportions in the popular conception, he remained the lodestar towards which every diplomat and foreign expert, opposition politician and prime ministerial candidate, turned for orientation.

Rail as it might, the population, it seemed, simply could not imagine a world without Mobutu. “We are a peaceful people,” Zaireans would say in self-exculpation, when asked why no frenzied assailant had ever burst from the crowd during one of Mobutu’s motorcades, brandishing a pistol. It was to take a foreign-backed uprising, dubbed “an invasion” by Zaireans themselves and coordinated by men who did not speak the local Lingala, to rid them of the man they claimed to loathe. The passivity infuriated, eventually blurring into contempt. Every people, expatriates would shrug, deserves the leader it gets.

My attempt to understand the puzzle kept returning me to HEART OF DARKNESS — not to the clichés of the headline writers, with their inverted, modernistic interpretations, but back to Conrad’s original meaning.

No man is a caricature, no individual can alone bear responsibility for a nation’s collapse. The disaster Zaire became, the dull political acquiescence of its people, had its roots in a history of extraordinary outside interference, as basic in motivation as it was elevated in rhetoric. The momentum behind Zaire’s free-fall was generated not by one man but thousands of compliant collaborators, at home and abroad.

Exploring the Alice-in-Wonderland universe they created I would belatedly learn respect. Stumbling upon the surreal alternative systems invented by ordinary Zaireans to cope with the anarchy, exasperation would be tempered by admiration. Above all, there would be anger at what Conrad’s Marlow, surveying the damage wrought by colonial conquerors who claimed to have Congo’s interests at heart, described as a “flabby, pretending, weak-eyed devil of a rapacious and pitiful folly.”

Michela Wrong spent six years covering the African continent for Reuters, the BBC, and the FINANCIAL TIMES. Her first book, IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF MR. KURTZ, won a PEN award for nonfiction. She lives in London and travels regularly to Africa. To read more and find her book, visit HARPERCOLLINS (©2000).