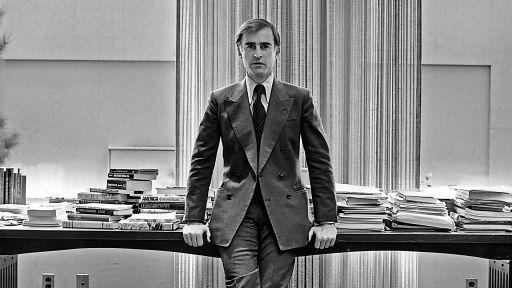

Ben Shapiro is a director, cinematographer and audio producer whose work spans more than 30 years with honors including two Peabodys and two Dupont Awards.

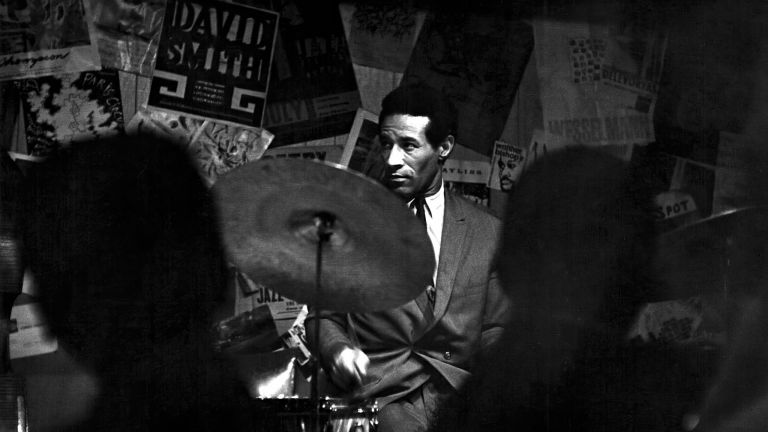

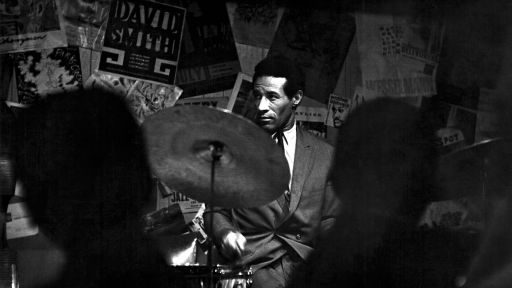

Alongside filmmaker Sam Pollard, Shapiro co-directed and co-produced Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes, an intimate documentary exploring the artist’s life as a drummer, activist, composer and innovator. In this interview, Shapiro discusses how this film – 30 years in the making – came to fruition, and the unique talent and legacy of Max Roach.

Read the companion interview with co-director Sam Pollard here.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: How did your partnership with Sam Pollard on this project begin?

BEN SHAPIRO: The story of how I first came to the project goes back to when I was a teenager and decided I want to learn to play the drums. I had the good fortune of working with a guy who was very knowledgeable about musical history, studying jazz drumming. He said right up front, if you want to learn, the key figure is Max Roach. That always stuck in my head.

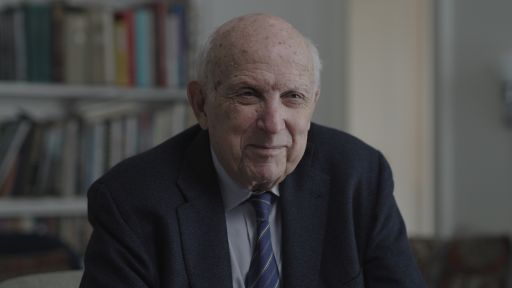

I met Sam from my work as a cinematographer. I was hired to work on a couple of projects he had directed. We got to be friends and through that, ended up talking a lot about artists, music and film. He had told me that he had started making this film about Max Roach. Meanwhile, I had been producing radio documentaries for NPR, and they commissioned me in the late 80s. One of the first things I did for them was a half hour radio documentary about Max Roach. So I went and interviewed Max Roach in his apartment, and later did another interview with him in the early 90s. That material ended up in the film; a lot of the Max voice over you hear comes from those interviews. I had that material and I knew Sam had this unfinished film and we decided we were going to take his material and mine, and combine them together to make the film that we did.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: While working with Sam and being part of that process, did your understanding of Max Roach’s music change at all given how long this was an ongoing project?

BEN SHAPIRO: I knew a fair amount about the music and his history, including his activism in relation to his music and process of creative reinvention, but certainly in the process of making the film, I learned a lot more about that history and details about the different creative process overall, as well as the different works and collaborations over his seven decades of work. Partly that was in the course of doing the interviews with people who worked with Max during that time. We were really fortunate to meet and talk extensively with people who had collaborated with him throughout his career. Really the inside experience of what that was like, which we felt was important to the film.

Jazz historiography often will look at the arc of the music of someone’s creative output over time, but it doesn’t as often look at the experience of the musician as creative artists in the contexts of what was going on socially, across their longer term goals and general experiences. Our hope was to explore and represent that in the film – that’s what I learned the most about in this process.

Another thing that factored into this, was that Max Roach left a vast archive of photographs, videos, home movies, recordings, contracts from his performances dating back to the 1950s. There were thousands of photographs dating back to the 1930s. So many that he must have been asking people to send him photographs. We had access to so many remarkable images. Apparently, we understood, he was very deliberate and conscious about it. Later in his life, he was working with an archivist to try and assemble and build that into an archive. He clearly felt he had a legacy. That archive is now at the Library of Congress. We went down to see it several times, and for days pored through that correspondence. From that you get a deeper sense of his life and experiences over time.

For me, it was a pleasure to work on this subject. Looking at how rich and vital his career was and his commitment, it’s very rewarding to dive into that work and collaborate with Sam Pollard.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: Did you have a sense from Max Roach what he hoped his legacy would be?

BEN SHAPIRO: Certainly he wanted to be remembered for his lifetime of creative work, I expect that’s what he would say.

The material in the archival primarily documents his creative life. Even the fact he was generous with his time speaks to that idea of legacy. When I first met him I was in my late 20s, I called him and told him that I wanted to do this audio documentary. I had the credentials from producing with NPR, but still, he was incredibly generous with his time, thoughts and ideas.

His music, his activism, his interest in working with movements for social change – all that—he saw as a whole, not divided. I think that certainly speaks to us today, how he combined those facets of his life into this large body of work.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: What do you feel makes Roach unique as a musician? How was he innovative within the percussion space?

BEN SHAPIRO: It’s funny, the movie presents me as this drummer. I describe myself as interested in history, but as a competent amateur drummer. But it’s a good question. It’s hard to pin it to one thing because his impact has been so broad. Overall, I would say that very occasionally musicians come along who set a model for how to approach the instrument–who you look at as a “before and after” in terms of how they approach their instrument; Max is certainly one of those. That itself is a legacy. His technical ability, how inventive he was with his performance, his composing. Abdullah Ibrahim talks about Max’s solos and he uses this word that’s very apt: he calls them “deep.” To me that means his drum solos have a certain richness. The fact that he could do that with these drum solos—and even when he wasn’t soloing–that has this kind of richness in terms of the execution and technical expertise, but also as composition.

BEN SHAPIRO: It’s funny, the movie presents me as this drummer. I describe myself as interested in history, but as a competent amateur drummer. But it’s a good question. It’s hard to pin it to one thing because his impact has been so broad. Overall, I would say that very occasionally musicians come along who set a model for how to approach the instrument–who you look at as a “before and after” in terms of how they approach their instrument; Max is certainly one of those. That itself is a legacy. His technical ability, how inventive he was with his performance, his composing. Abdullah Ibrahim talks about Max’s solos and he uses this word that’s very apt: he calls them “deep.” To me that means his drum solos have a certain richness. The fact that he could do that with these drum solos—and even when he wasn’t soloing–that has this kind of richness in terms of the execution and technical expertise, but also as composition.

I’ve seen the film so many times, but I was at a film festival the other day watching it again with an audience. There was one of the solos he did “For Big Sid,” – which is dedicated to a drummer from the 30s Big Sid Catlett that had been an influence on him – I was watching and I really saw it in a new way. There’s a whole thing he’s doing that I hadn’t really seen before. The depth of the composition on the drumset is remarkable. You can say “here’s the drumset,” but it isn’t just something to do with timekeeping or an accompanying instrument, it is an instrument where you can do those kind of deep solos. No one had ever done that before as Max did. That speaks to the instrument and what it’s capable of, and what the drummer is capable of.

There are also things too, about Max and other drummers in terms of specific technical ability, but for me it’s the sheer inventiveness. He tried to explore every possibility he could on that instrument, from how you move around the drumset, to rhythmic things you do with the different parts of the set, or the overall way you approach the instrument with a whole new kind of flexibility. Just this brilliant inventiveness that was supported by this astounding technical ability. As a drummer, I look at his playing and marvel. It seems so effortless.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: I appreciated that your film explores and explains what a percussionist brings to a piece. Even for people who aren’t musicians, I think you can still feel that “depth” he’s bringing to make it feel powerful.

BEN SHAPIRO: There are a couple of things that Sonny Rollins said that relates to that. He talks about how the drummer plays back and forth with the instrumentalists, which happens with all members of a jazz group. But specifically he said he had an ongoing dialogue with Max as he was playing, that would elevate what he was doing, make what he was doing better and give him ideas. I think that Max advanced this dynamic interaction between the drummer and the others in the band and the band as a whole.

Something else Sonny mentions about the Max Roach and Clifford Brown group, whose recordings are still vitally important today. He said that in a way that band “was about Max Roach.” What he means is that while Max was playing drums, he was directing the group, rhythmically, dynamically, and articulating his musical ideas for the group.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: There are two things that drummer Kendrick Scott said which remind of me that. One that Max Roach is conversational, which is exactly what you’re saying, but he also said Max “dared to be patient.”

BEN SHAPIRO: What strikes me about the being patient statement is Roach’s repeated innovation. It’s one thing to become renowned and respected as he was–in the 1950s he was famous even beyond the music world. But then, to go from that and say “okay, I’m going to develop a new conception and start from scratch.” That to me speaks to a different kind of patience. Like with his percussion ensemble, M’Boom, which was a radically new idea. He had to build that up from zero through rehearsals and it was years before they could get to the point of playing concerts or recording. That’s a different kind of patience.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: Yeah, definitely, creating art for a world that might not be ready for it is certainly a daring kind of patience.

BEN SHAPIRO: Yeah! Saying, “It’s going to take time, we’re going to invest our time and we don’t know what we’re going to get, but we’re going to pursue that because that’s our vision.” For any creative person, it’s another way he can be an inspiration.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: A bit of an abstract question, but do you feel like there is a relationship or similarity between drumming and filmmaking?

BEN SHAPIRO: Of course there a lot of ways you can look at Max Roach as a creative inspiration, or on how to lead a creative life. I think a lot of what he did applies in the pursuit of newness and exploration, as well as relating to the world around you and social or creative movements that you can aspire to.

You could also consider that both filmmaking and so-called jazz music both start from this place where you have an idea, and you assemble the elements, you work with these to try and create a structure that has an effective form. With jazz, one of the marvels is that this happens spontaneously, improvised in real time. Obviously film is different, we worked on this film for years, but we were constantly re-trying and re-thinking things, which is probably true of any art. I’ve thought sometimes in terms of documentary, when you’re filming live things happenings in the moment and responding to those things as you shoot, visually, perhaps thematically– there can something improvisational, real-time, in the way that playing in a jazz ensemble is real-time.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: I think documentary filmmaking can be very improvisational. Especially as the footage you get can change the direction of your vision.

BEN SHAPIRO: It is in a slower sense. Interviewing can certainly be an improvisational exercise, because both in a jazz group and interview there’s an existing form with some structure. You have this idea that you want to tell this larger story, often a beginning, middle and end – but then things come up and ideally you’re responsive to the interview subject, adapt and improvise as you go.

CRISTIANA LOMBARDO: Thinking about Max as an inspiration for creatives, do you feel he has a spiritual successor?

BEN SHAPIRO: It’s hard to make these big proclamations of a successor in terms of a history that’s so rich and brilliant with so many masterful artists. I would look more at the ideas that Max bequeathed to those that followed. I think you can look at generations of brilliant percussionists and the impact he has had on them. Certainly you can look at drummers such as Tony Williams or Elvin Jones—and many other innovative drummers that came after him.

But more broadly, he was a member of a generation that really shifted the idea of what you could do musically. And he did that again and again. That I think is an important legacy: the understanding of the broad possibilities of what music can be–an attitude that the possibilities of music are boundless.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.