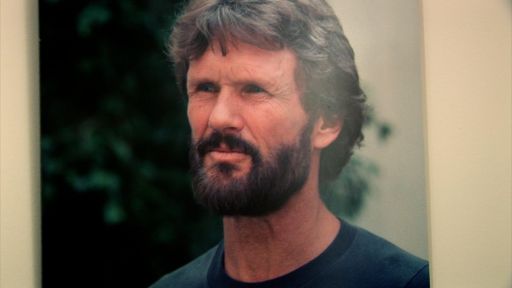

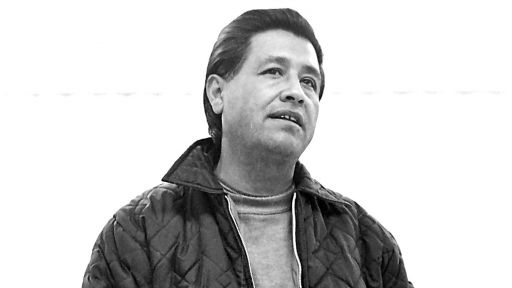

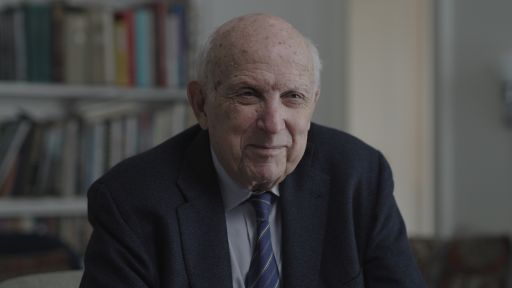

I first knew Richard Anthony “Cheech” Marin as one half of the timeless stoner comedy act Cheech and Chong. But once I dug just an inch beneath that surface, I came to know Cheech Marin the art collector, cultural communicator and Chicano legend.

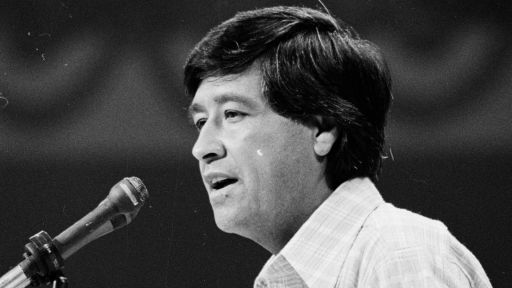

Ahead of the broadcast premiere of A Song for Cesar, I spent some time talking with Marin to pick his brain on the Chicano Movement and on labor leader Cesar Chavez’s role in pushing it forward.

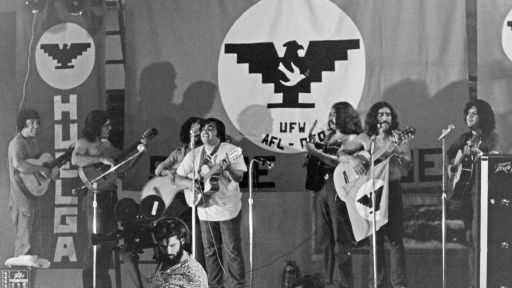

CHEECH MARIN: I heard about Cesar when I was in college, when he first started his movement in the mid to late 60s. Everybody was so glad to see he was representing some unrepresented parts of society—and with a firm resolve, too.

JOE SKINNER: What do you appreciate about the way Chavez carried himself in life and in the farmworkers’ movement?

MARIN: You know, I was really surprised. I met him a couple times, but the first time I met him I think I was still in college or something. They were doing a rally and Tommy [Chong] and I went and what I was really surprised about was his sense of humor. He had a great sense of humor, he’s always smiling. You kind of had this picture of this really stern union leader or movement leader, and it was always quite the opposite. He was always very amiable to everybody around him and had a great sense of humor. I guess you need that to make it through the kind of thing he was going through, and to represent or fight for the things that he was trying to accomplish. So this is really a man of the people. This is not a fiery leader. He was a fiery leader, but kind of a mild killer. He said all the things that he had to say. It was amazing. I was really taken by him. The first time I met him, he knew who we were. He knew our comedy. He just treated us like a member of the family, and I was just amazed by that.

SKINNER: How can comedy impact a cause like the Chicano Movement and the farmworkers’ movement?

MARIN: Chicanos have a great sense of humor, because it’s family oriented more than anything. The Chicano Movement was always family oriented. So you got a big turnout there when you went, because everybody in the family went—the kids, the mother, the father, the grandparents. So there was always a sense of “don’t take the pinche play so seriously.”

•• ━━━━━ ••●•• ━━━━━ ••

The line Marin uses, “don’t take the pinche play so seriously,” comes from Luis Valdez’s critically acclaimed 1979 stage drama, “Zoot Suit,” and its 1981 film adaptation.

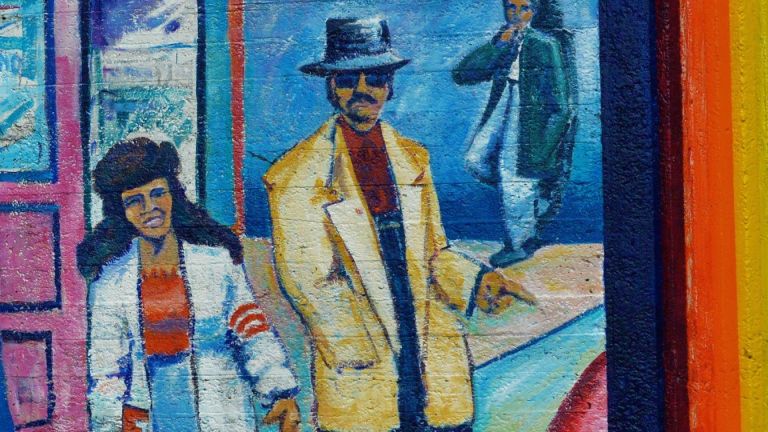

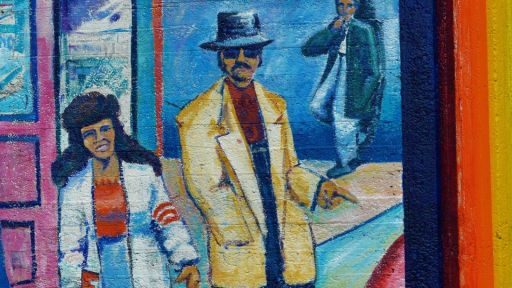

It was the first Chicano play on Broadway, which notably blends meta narratives around entertainment alongside a dramatic retelling of 1943’s Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles, California. The symbolism of the zoot suit would come to inspire Chicanos during the Chicano Movement, including leaders like Cesar Chavez.

It is art and entertainment like “Zoot Suit” that Marin refers to as a great way to “chronicle” culture in Chicano neighborhoods, and to take note of “how some things have changed, and how some things have not changed.”

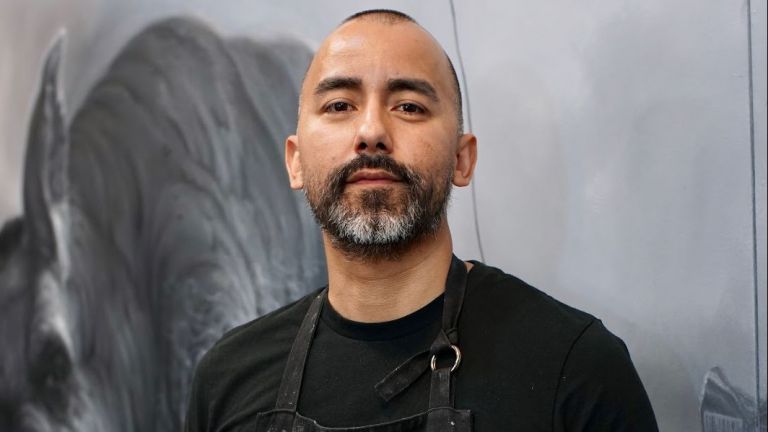

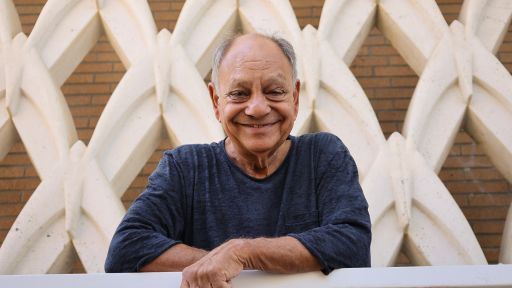

Marin has a sharp wit about him and a light and joyous presence on Zoom calls, but he certainly does take art seriously. His interests have led him to establish The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art, Culture & Industry, which you can also just call The Cheech. It houses hundreds of Chicano artworks from Marin’s personal collection.

SKINNER: What do you think makes art such a powerful force in social movements and in culture?

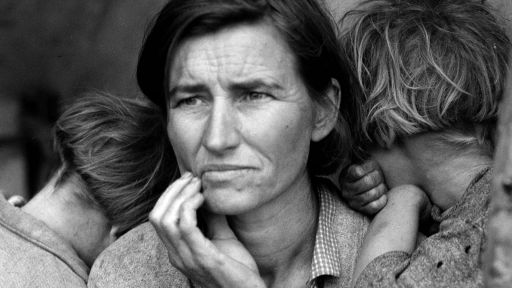

MARIN: I think it’s because it’s easy to understand. I mean, it goes to that adage that a picture is worth a thousand words. The Chicano muralists took their cue from the Mexican muralists who were doing the same thing in the Mexican Revolution. But playing to an audience—providing art for an audience—that was largely illiterate. And so pictures did speak a thousand words. They saw what was going on in a picture in murals by David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera.

MARIN: Now, the Chicanos took that and furthered it, it was a little even more sophisticated because their audience was not illiterate. They were very literate. Putting those images in front of them, they were motivators, where they could see it very clearly what we’re talking about with what the movement was about. You identify with it more easily than with rhetoric. As each new generation, each new artist comes into the field, I would call it “news from the front.” This is what my neighborhood looks like. These are the problems in mine.  This is what the people look like. These were the kids, the older people. This was what my playground and what our neighborhood looks like. And you communicate in that method. And it changes as your neighborhoods change. “Oh no, my neighborhood’s getting gentrified.” What does that look like? So there’s always movement, there’s always movement. As the population of Chicanos gets more and more educated with a college degree or even high school, the ability to understand and identify with that movement becomes easier and more pronounced. I mean, I’m a third generation [Angeleno]. My kids are fourth generation, and you see that they—like me—believe that all the promises that were made to the citizens of United States applied to me. I think, increasingly, the new generations think that all the promises guaranteed and promised to the American public, they belong to us, too.

This is what the people look like. These were the kids, the older people. This was what my playground and what our neighborhood looks like. And you communicate in that method. And it changes as your neighborhoods change. “Oh no, my neighborhood’s getting gentrified.” What does that look like? So there’s always movement, there’s always movement. As the population of Chicanos gets more and more educated with a college degree or even high school, the ability to understand and identify with that movement becomes easier and more pronounced. I mean, I’m a third generation [Angeleno]. My kids are fourth generation, and you see that they—like me—believe that all the promises that were made to the citizens of United States applied to me. I think, increasingly, the new generations think that all the promises guaranteed and promised to the American public, they belong to us, too.

SKINNER: Is there a particular artist you’re working right now that you’re excited about, who you think is carrying this torch?

MARIN: A lot of them are. There’s Vincent Valdez, a young guy from Texas, and when I did the “Chicano Visions” tour, he was the youngest artist in the show, and he had just graduated from Rhode Island School of Design. His thesis for graduation was the painting “Kill the Pachuco Bastard!,” which chronicled the zoot suit riots that were a real, real thing during the 40s.

•• ━━━━━ ••●•• ━━━━━ ••

In a time when cultural gestures and artistic statements are quick to be tried by the court of public opinion, Cheech Marin has long advocated in defense of free artistic expression. He holds that virtue sacrosanct.

MARIN: Telling artists what to make is a useless proposition. It goes against the process. They’ll make what they want to make. All Chicano artists that I know of, they come to a point where they just want to pursue their own artistic concerns, whether it is relationships with their parents, their kids, their neighborhood, or their government. So they can be all-encompassing, because [Chicano] is not a painting style, it is a description of culture. And everybody has their own description of culture.

SKINNER: Was there a moment when you were growing up when you realized how important Chicano identity would come to be for you?

MARIN: Yeah, it was a derogatory term at the beginning from Mexicans to other Mexicans. The Mexicans who had moved from Mexico and now were living in tin shacks along the borders were no longer truly Mexicanos because they had left their country. They were something less.  They were “Chicos.” They were little “Chicanos,” little satellite Mexicans, living on the other side of the border. I grew up half the time in an all-Black neighborhood and then half the time in an all-white neighborhood. I was always “Mexican,” “Yo, Mexican!” I’m not Mexican. I have never been to Mexico. I don’t speak Spanish. So how am I Mexican? So I was always struggling. But I knew I was partly [Mexican]. Everybody in my family was Mexican. They spoke Spanish. My grandparents and my mom and dad and uncles and aunts . . . But I was always searching for what describes me in this process. I tell this story every so often: One time I came home to dinner and there was a family gathering going on. And my Uncle Rudy, who I knew all my life, he was a policeman, as was my father. He was LAPD. And he was telling the story about how he went to get his car fixed at some mechanic, and he said, “He wants $200 to fix it! Give me a piece of tinfoil and pliers and I can fix that. I’m a Chicano mechanic.” And I go, “That’s what I am!” I’m a guy who can survive under any circumstances and doesn’t let anything stop him. “Okay, it costs too much. I’ll make something else. It doesn’t cost much, but it does the job.” You know, it’s that great rasquache attitude that really, really resonated with me. I could speak Spanish or not. I could speak Spanglish or not. I can eat Mexican food or Bob’s Big Boy hamburgers. It doesn’t matter. I am part of that Chicano Movement, and it really described a lot.

They were “Chicos.” They were little “Chicanos,” little satellite Mexicans, living on the other side of the border. I grew up half the time in an all-Black neighborhood and then half the time in an all-white neighborhood. I was always “Mexican,” “Yo, Mexican!” I’m not Mexican. I have never been to Mexico. I don’t speak Spanish. So how am I Mexican? So I was always struggling. But I knew I was partly [Mexican]. Everybody in my family was Mexican. They spoke Spanish. My grandparents and my mom and dad and uncles and aunts . . . But I was always searching for what describes me in this process. I tell this story every so often: One time I came home to dinner and there was a family gathering going on. And my Uncle Rudy, who I knew all my life, he was a policeman, as was my father. He was LAPD. And he was telling the story about how he went to get his car fixed at some mechanic, and he said, “He wants $200 to fix it! Give me a piece of tinfoil and pliers and I can fix that. I’m a Chicano mechanic.” And I go, “That’s what I am!” I’m a guy who can survive under any circumstances and doesn’t let anything stop him. “Okay, it costs too much. I’ll make something else. It doesn’t cost much, but it does the job.” You know, it’s that great rasquache attitude that really, really resonated with me. I could speak Spanish or not. I could speak Spanglish or not. I can eat Mexican food or Bob’s Big Boy hamburgers. It doesn’t matter. I am part of that Chicano Movement, and it really described a lot.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.