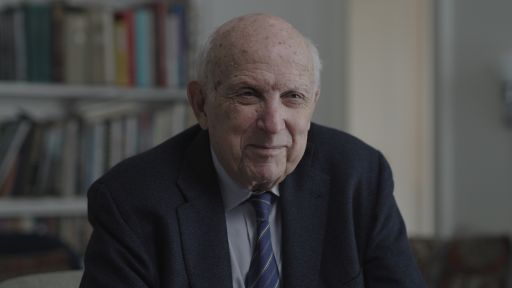

Sam Pollard is the co-director and co-producer of Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes, a portrait of the inimitable drummer and composer Max Roach.

A prolific filmmaker, Pollard has directed or produced several American Masters documentaries including: Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Got to Be Me, August Wilson: The Ground on Which I Stand, Marvin Gaye: What’s Going On and Zora Neale Hurston: Jump at the Sun.

I sat down with the Academy Award-nominated, multi-Emmy-winning filmmaker earlier this month to discuss the 30-year process of making the film, what makes Roach such a compelling artist and performer and what today’s artists can learn from his life and his work.

JUNE JENNINGS: I just wanted to begin by saying congratulations again on the film. It’s a beautiful portrait and feels both timely and timeless. As you’ve mentioned in other contexts, this film, Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes, has been about 30 plus years in the making. How did you first set out to tell this particular story, and what inspired you to keep working on it for decades?

SAM POLLARD: In 1983, I was editing a documentary about the poet Langston Hughes for the late filmmaker St. Clair Bourne, and [for] one of the segments in the film, St. had asked Max Roach to perform a drum solo to one of Langston’s poems. And I cut that sequence. I had been a big fan of Max as a jazz person. And I said to St. after I cut the scene, “Somebody should make a film about Max Roach.” And he turned and said, “You should do it.” I was stunned because I had never made a film before. I’ve just been an editor. I had never directed a film.

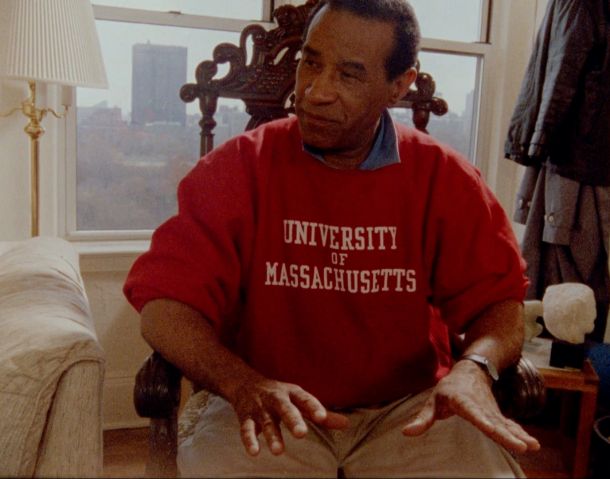

And so, he introduced me to Max a few months later. And he brought together [me] and the associate producer on the Langston Hughes film, a woman named Dolores Elliott, and said, “She should produce, you should direct.” So, she put together a proposal. We got our first grant from the New York State Council of the Arts in 1985 or 86, something like that. And we shot a long interview with Max at his apartment over on 100th Street in Central Park West. And then we went with him to San Diego and shot with him when he was doing the score for a contemporary version of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” And then we were able to get some money from his record company in 1987 or ‘88 to go with him to Milan, where he was doing a concert with a string and woodwind ensemble. And I started the journey.

And I spent, I think I spent from 87 to 92-93 hanging out with Max off and on. You know, I did some work for him on some other projects that he wanted me to shoot. And so it was really a really great experience for me.

But then I put the first cut together the film, in 88, 89, I looked at it, and I was very unhappy with the cut. I didn’t like it. I think a lot of it had to do with the fact that it was the first film that I ever directed. And I wasn’t happy. I think I even showed the cut to Max, which was probably a mistake. And he had a lot of comments and stuff which, you know, frightened me. So, I put it on the shelf for, like, five years, six years.

I took it down when I was teaching at NYU. And I showed some students and they gave me some suggestions. And I shot some additional interviews with some of the musicians who would perform with Max — not the ones who are in the film now. I re-cut it, looked at it again, still wasn’t happy, put it on the shelf again. I was just not ecstatic about where it was going.

And then around 2014-2015, [co-director and co-producer] Ben Shapiro — who I had known for years, was also a big jazz fan and a former drummer, had done audio interviews with Max in the late 80s around the same time I was shooting — said he wanted to look at my footage. I showed it to him. And he said, “We have to try to figure out how to finish.” I said “Well, would you co-direct with me?” And he said yes. And we were able to raise more money. Then we decided to shoot all of these additional interviews, the ones that you see in the film: Randy Weston, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Greg Tate, Questlove. And we were able to raise money shoot the additional interviews and finally get to film to a place that we thought that we thought it could be a film. So it took a long time. Longest film it ever took me to make.

JUNE JENNINGS: So in many ways, this is one of the first projects that you endeavored on as a director that’s finally coming out several years later.

SAM POLLARD: It was the first one.

JUNE JENNINGS: Wow. Do you see a way in which his story or work is different now than when you first began filming? Has your perspective on him changed at all in the intervening decades?

SAM POLLARD: Quite honestly, no. My perspective is still the same. I think he’s one of the greatest American musicians ever on the planet. I think that his activism is still very powerful to me. He understood that he wasn’t just going to be an entertainer. But he also knew [he] wanted to make music that would politically and socially make a difference. And the way I felt about him back in the 80s is the same way I feel about today. I just think he was an advocate for social change, a great drummer, you know, who never rested on his laurels. And he was always challenging himself, both musically, socially and politically. So the way I felt about him in the 80s is how I feel about him in 2023.

JUNE JENNINGS: One of my favorite quotes from the film, which comes from Harry Belafonte, encapsulates this idea of Roach’s timelessness and his regal-ness. He says, “He wasn’t trying to be anything. He was already it.” And as you even say, he’s got such a regal quality about him. And what I just think comes across so strongly for me in the film is just this equal attention paid to his dignity as a performer and sort of his audacity as an artist.

SAM POLLARD: Those are good phrases: his “dignity as a performer” and his “audacity as an artist.” That’s exactly what Max Roach was all about.

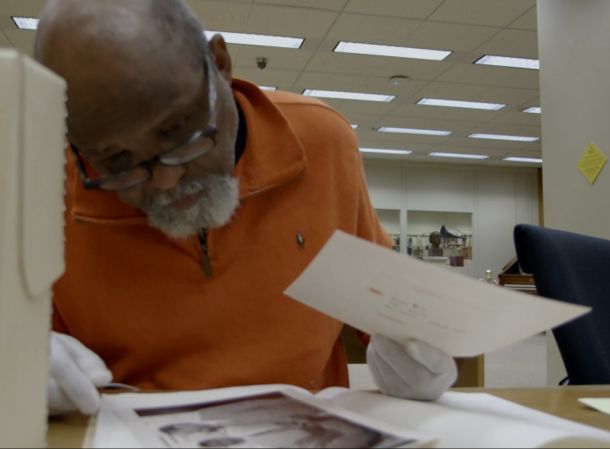

JUNE JENNINGS: I also want to just talk a little bit about how you also make an appearance in the film as well. How did you decide to intervene on-screen in the in the way that you did, and break the fourth wall and give a little bit of an insight into your process of getting to know Max Roach?

SAM POLLARD: Quite honestly, it wasn’t my or Ben’s idea. It was [American Masters executive producer] Michael Kantor’s idea. And we both initially were reluctant. I’m always opposed to the idea of the filmmaker being a part of the filming process. I always think it’s a little strange. I mean, people do it. Michael Moore does it, Errol Morris. But I was sort of like, “Ah, I don’t want to be in the film.” And so we talked about it over and over. And we finally decided, okay, we should do it.

There had been this young man in 1983 who had shot interviews and verité footage of me working at the Steenbeck, this place where I used to work as an editor. So I reached out to him and said, “You know, Joel, is it possible that I can look at some of the footage and maybe use some of it for this Max Roach film?” He consented. We [also] already had footage of when we went to the Smithsonian, as you see in the film. We shot that thinking that we may want to try to use it in the film at some point, but then we thought, “Nah, we won’t do it.” And then Michael mentioned it, and we thought about it, and we finally said, “Okay, let’s put it in.”

JUNE JENNINGS: So you’re very much in these spaces with him documenting his performances. Do you have an awareness that you’re not only working on this film but also documenting his creative history and his history as a performer?

SAM POLLARD: Oh, absolutely. Quite honestly, that’s probably the most invaluable thing to me in doing these films about artist types. That you have the opportunity, and they have been generous enough, to let you see the process. I really liked that a lot. I’m a great believer in the notion of process. That’s why I’ve loved being an editor so many years. Because of the process of creating something, and then seeing the fruition of it. So to see Max perform with other musicians, it was a wonderful thing to do.

It’s like when I make a film, and I’m engaged with an editor or director of photography, or producer, and we’re trying to figure out how to tell the story or shoot the material. That’s just a wonderful part of the process. That was one of the things that excited me about doing a film about a gentleman like Mr. Roach, I could see the process. And I could be involved in the process.

JUNE JENNINGS: And do you see any striking similarities between making music or making a film? Is it that collaboration, or is there some other element?

Well, if I had not been a filmmaker, I would have wanted to be a musician. I love music. And to me, it’s much like making film. You have these elements that you find, you put them together and you create something that’s a film or a musical composition or a band. It’s the same to me. So, sure, I love the idea that making films is much like making music. It’s about working with collaborators to find something or that comes to come to the point where you all feel like, “We made something happen.” Yeah. And that, to me is the wonderful part.

JUNE JENNINGS: Your films have been described by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. as “a way of telling African American history in its various dimensions.” How do you see this film about Max Roach sort of fitting into your larger body of work?

SAM POLLARD: Oh, clearly. Very easily. These films that I’ve done about Max or Sammy Davis, Jr. or August Wilson or Slavery by Another Name or Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered are all important touchstones in terms of understanding and digging into the African American experience. That’s very, very important to me as an African American male. And it was a long journey for me to get from thinking that race didn’t matter to where I understand that who I am, as a person of color, does matter. And that if you want to understand American history, you have to understand the African American experience, you have to understand the Native American  experience, the Latin American experience. You’ve got to understand all the experiences.

experience, the Latin American experience. You’ve got to understand all the experiences.

I grew up in in America, like a lot of people, where our history has always been considered secondary. And the challenge that I was faced with it and that I grabbed on to wholeheartedly was that our experience is the American experience. And if you don’t understand our experience, you’re only getting a slice of what America’s all about. When I grew up, everybody in my school years were Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt and George Washington. It took until my teens, and being involved with other African Americans, to learn about Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, George Washington Carver, W.E.B. Du Bois, Nat Turner, Malcom X and Dr. King, you know, I had to learn that history, which I’ve passed onto my own children.

JUNE JENNINGS: I really appreciate your response, around seeing this film as part of your purpose as a filmmaker and how you look at each of your projects. And so shifting gears a bit, Max Roach is considered one of American Masters’ Thought Leaders. From your point of view, how do you see Max Roach as being a Thought Leader?

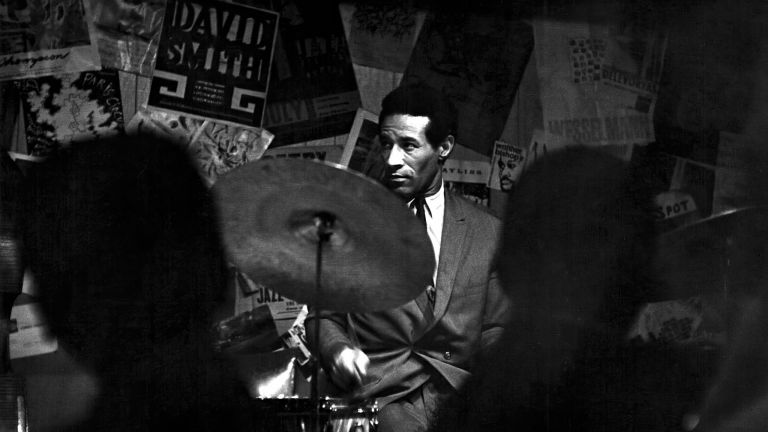

SAM POLLARD: Think of it this way. Here’s a gentleman who grew up in New York City in the 30s and 40s. Here’s a gentleman who became committed and passionate about playing so-called “jazz,” African American music. Here’s a gentleman whose ability as a drummer led him to be engaged with the great heroes of that music in the 40s: Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, so many others. Here’s a gentleman who realized that by the 50s, he wanted to find his own voice, so he creates his own band with Clifford Brown, Harold Land, Sonny Rollins, George Morrow and Richie Powell.

But here’s a gentleman who knew that by the end of the 50s, with the burgeoning civil rights movement, that there had to be more than just playing the songs of the day. He realized that he had a commitment to create music that was going to speak to the issues of what it meant to be an African American in the turbulent 50s and the 60s. That’s what led to him to doing We Insist! [Max Roach’s] Freedom Now Suite. That’s what led to him creating the song “Tears for Johannesburg.” That’s what led to him led to him doing solos [with] “I Have a Dream.” That’s what led to him being involved politically, protesting not only what was happening in America but places like South Africa.

This was a man who understood that to be a musician didn’t mean that you just be about playing the tunes that you learned in the 40s and 50s. It meant challenging the American status quo on racism. And that’s what he did. That’s why he’s a Thought Leader.

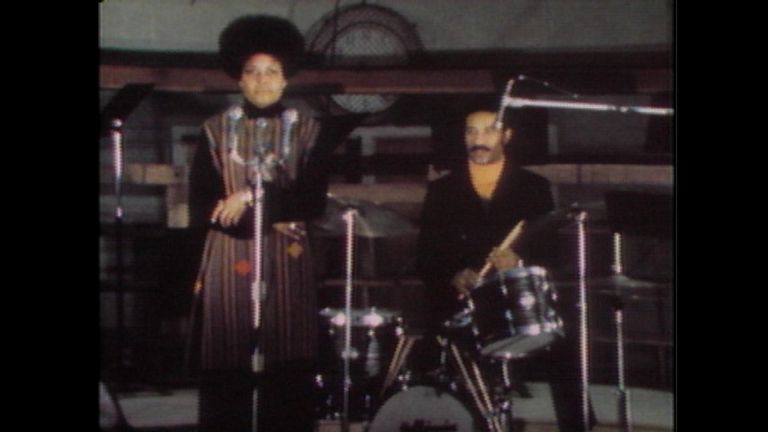

JUNE JENNINGS: And in one of my favorite parts of the film is when he is talking about giving these historical monologues before he plays, and folks who worked at venues were like, “You can’t do that. You can’t talk about Marcus Garvey, you can’t talk about this person, you can’t talk about this event.” And he was insisting.

SAM POLLARD: That’s why he wasn’t invited by back by some of those clubs.

JUNE JENNINGS: I found that so interesting. He insisted on contextualizing what’s going on onstage and what’s going on in the world with what he was doing. And saying “I’m not letting you tell me I can’t give context to what I’m doing. I won’t just like, you know” — how we say nowadays — ‘shut up and dribble.’ I’m not going to do that.”

SAM POLLARD: And he didn’t. I mean, I used to see him in clubs when he did those speeches. I remember when he was performing those at the Village Vanguard. And, Lorraine Gordon, who ran the club basically said, “I love seeing Max perform, but I wish he would stop talking.” She used to book Max and his band, but then she was reluctant to book [them] because she knew that he would get on a political platform.

JUNE JENNINGS: And so given the way he wanted to engage with the audience, and imbue the work of his life with political urgency, what can today’s generation of performers, artists and activists look at in his life and learn from?

SAM POLLARD: It just says that a performer has an obligation and ability to do more than just entertain. Now, you know and I know that there will be some who think [entertaining] is all they need to do. They don’t want to do anything else. But if you have any sense of social or political awareness, you should be able to challenge yourself and say, “Let me speak out.”

You know, as much as I don’t really care about Taylor Swift’s music, I like the fact that she speaks up. You know, that’s important, you know, and if a performer can do that, that says a lot about them, where they’re coming from, what they’re thinking about in terms of who they are and what their place is in this society. Not everybody’s gonna do it. I mean, you can’t make people do it. But she understands, like Max understood.

JUNE JENNINGS: So, they see that their platform gives them the responsibility?

SAM POLLARD: I mean, listen. Some should. You would hope that artists would see their platforms about being more than just entertaining, but we’re all human. You can’t make some people be more socially aware, politically aware. It’s not who they are.

JUNE JENNINGS: I think that that’s really important to understand, that the idea of a platform falls differently on people and what they choose to do with it.

SAM POLLARD: That’s exactly right.

JUNE JENNINGS: Because some people think that people are like, “Oh, like, well, I’m out here, there’s a lot going on in the world, I don’t want to really bring that into what I’m doing. I just want to make people you know, feel inspired or feel uplifted, or just feel happy for this indeterminate amount of time versus.” They may see it as bringing the issues into the work. But I think in some ways, like you’re saying, some people have figured out how to. And at the height of this, someone like Max Roach is doing this, but it feels natural, it feels imperative, it feels urgent to do so.

SAM POLLARD: Yeah. I mean — you know this — there’s some people who say that’s not what they’re about, in all work and walks of life. Some people will say “I have an important thing to say, and I want to say it.”

The reason is that someone like Tupac is still so relevant is because he was political. You know, he was political when he was rapping, you know, besides to other ways he was, into his music. And that’s what some artists do. So some are going to be political and some are not.

JUNE JENNINGS: Are there any other moments from filming or the process of creating the film that still resonate with you? Or maybe in some way help you sort of unlock or unpack something at some point? Any sort of “aha” moments while filming over the years?

SAM POLLARD: The best “aha” moment for me was when we showed Ayo Roach the footage of her and her sisters as little girls. Yeah, that was a wonderful moment. You see it in the film, she’s watching the footage of her and her sister when they were little girls. That was a wonderful, wonderful moment to me.

The other “aha” moment was when Dee Dee Bridgewater told the two stories. One story was when she said she was in France, and Max was keen to see her. And he was hiding behind the newspaper. And she was saying “Max is feeling paranoid.” She’s saying “Max, nobody is trying to hurt you.” And then the other story she told was when she did one of the songs from Freedom Now Suite how Max mentally thought she was Abbey Lincoln, and started calling her those horrible names and he later apologized. He was a complicated guy, you know. He had issues, we know, in terms of his relationship with Abbey Lincoln, he had anger issues. I didn’t know those two stories. So those were, like, “Whoa.”

Part of me as a filmmaker, and Ben felt the same way too, was we didn’t just want to create this sort of piece about Max where everything was hunky dory. We wanted to show that this guy had some dark sides, which we all have.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.