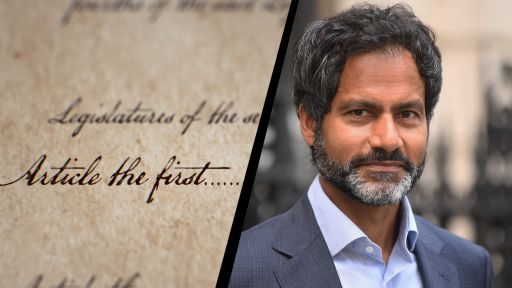

A singular figure in our legal landscape, Floyd Abrams has argued before the Supreme Court thirteen times and has been part of many of the most sensational and important First Amendment cases of the last century.

His work has contributed to our understanding of the First Amendment for decades. This timeline explores Abrams’ Supreme Court arguments and some of his other most seminal cases:

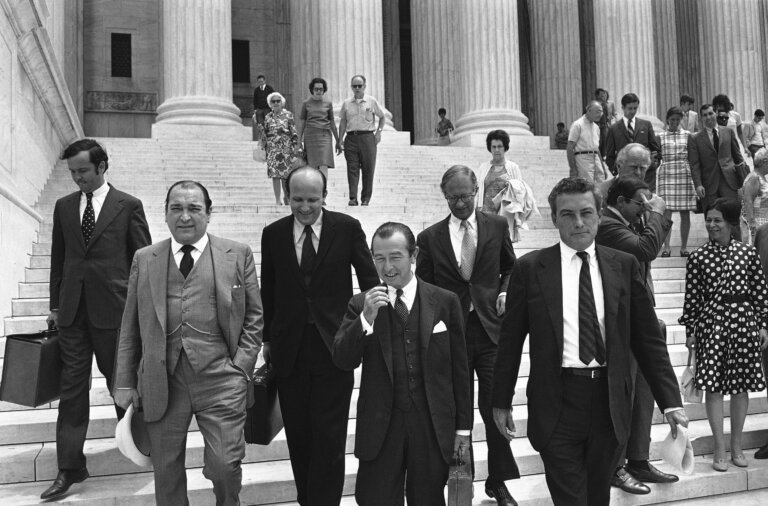

New York Times Co. v. United States (AKA “The Pentagon Papers”)

While a partner at Cahill Gordon and Reidel, Abrams was part of the legal team defending the Times' decision to publish a number of confidential documents containing information about the cost of the Vietnam War. This case is one of the most important pieces of legislation protecting press freedoms from the government and cemented Abrams' reputation as one of the top First Amendment attorneys.

Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart

In his first oral arguments at the Supreme Court, Floyd Abrams argued for the Nebraska Press Association. During a high-profile murder trial, Judge Hugh Stuart, a Nebraska State Trial Judge, ordered members of the press to refrain from publishing accounts of confessions made by the accused murderer to the police that could bias potential jurors. This sort of prejudicial censorship is called prior restraints. Abrams successfully argued that prior restraints on media coverage during criminal trials was a violation of the First Amendment and that the court had alternative means of ensuring a fair trial for the accused.

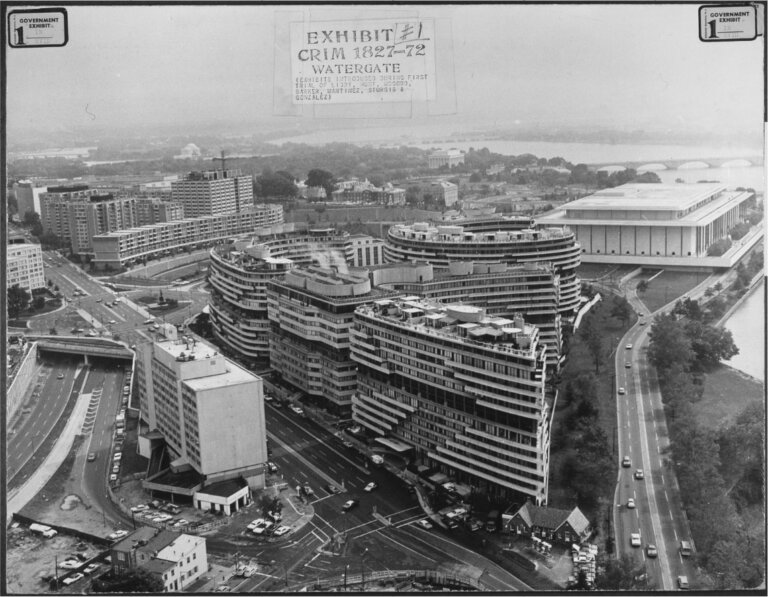

Nixon v. Warner Communications, Inc.

In 1977, several of Nixon’s advisors were on trial for conspiring to obstruct justice during the Watergate scandal. During the trial, about 22 hours of tape recordings of conversations in Nixon’s offices were played to the jury. While the public and the press were provided with transcripts of the recordings, Warner Communications and Abrams argued that the tapes themselves (being evidence in a public trial) should be released to the broadcaster and the public. Ultimately, the Supreme Court decided against Abrams, stating that since the advisors (who were initially convicted) were planning to appeal, the prejudice such a broadcast would cause out-weighed the public’s right of access considering the transcript was already available. Additionally, they decided that this case did not concern the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of the press because the tapes were never available to the public and the press has no right to information about a trial that the public does not already have.

Landmark Communications, Inc. v. Virginia

While Abrams had addressed the Supreme Court before, this was the first time he did so alone. A Landmark Communications newspaper, The Virginian Pilot, published a truthful article that stated that Judge H. Warrington Sharp was under investigation by a judicial fitness panel, implying that Sharp was unfit for his position as a public official. Under Virginian law, such investigations are supposed to remain confidential, so The Pilot was convicted without a jury and fined $500. When the case made its way to the Supreme Court, Abrams made a broad argument that by the First Amendment, the press should never be punished for printing the truth when that information is lawfully obtained. While the Court refused Abrams' broad argument, they did vote unanimously with him and Landmark Communications, stating that protecting a judge’s reputation was insufficient grounds for criminal charges.

Herbert v. Lando

Anthony Herbert was a Vietnam veteran who publicly accused some of his fellow officers of covering up war crimes. CBS then aired a documentary that Herbert claimed was libel. Since he was a public figure, Herbert needed to prove that the documentary was published with “actual malice,” meaning they either knew their statements were false, or recklessly disregarded whether they were false or not. To do so, Herbert targeted the film's editor, Barry Lando, among other individuals, to get insight into the editorial process and prove actual malice. Abrams argued that the First Amendment protected the editorial process and that the state of mind of those who edit and produce such projects did not need to be disclosed in this case. The Supreme Court, however, was not convinced and ultimately decided that the editorial process and the thoughts, opinions and conclusions associated with it are not protected by the First Amendment in cases of libel and are valid evidence.

Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Co.

After a school shooting, The Daily Mail used lawful reporting techniques to learn the name of the alleged juvenile shooter. Upon publishing that information, they were indicted for violating a West Virginian statute that makes it illegal to publish the name of a juvenile defender without permission from the juvenile court. Abrams argued to the Supreme Court on behalf of the Daily Mail that this statue was a clear example of “prior restraint,” a form of censorship that allows the government to review materials and prevent their publication and was therefore a violation of the First Amendment. The court unanimously agreed with Abrams, stating that restricting lawfully obtained truthful information will “seldom satisfy constitutional standards.” A step closer to Abrams’ broad argument from Landmark Communications, Inc. v. Virginia.

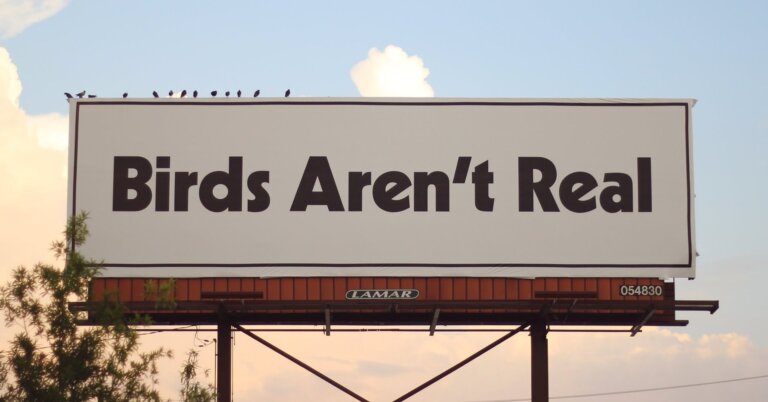

Metromedia, Inc. v. City of San Diego

The City of San Diego, California passed an ordinance to ban outdoor display signs. There were many exceptions to the ban including temporary political signs, government signs, bus stops and on-site commercial advertising (meaning a sign advertising goods and services available where the sign is located). Metromedia, a billboard company, as represented by Abrams, sued, claiming that the ordinance discriminated against noncommercial speech which sometimes appears in billboards, since it was not allowed in any of the exclusions and commercial speech was allowed on-site. While the Supreme Court was split, they ultimately decided that Abrams' argument was solid and that banning billboards violated the First Amendment.

CBS, Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission (FCC)

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 allows the FCC to punish broadcasters who don’t allow legally qualified federal candidates to purchase a reasonable amount of time to support their campaigns. In October of 1979, Jimmy Carter’s campaign requested time for a 30-minute program from CBS, ABC and NBC. They each refused saying that it was too early to sell political time for the 1980 election. The Carter campaign then reported the stations to the FCC. Abrams and CBS tried to argue that the First Amendment’s guarantee of Freedom of the Press granted them the right to decline to sell time to the Carter campaign. The Supreme Court did not agree and insisted that the Federal Election Campaign Act granted broad access to broadcast time to federal candidates.

Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. National Enterprises

In 1977, Gerald Ford contracted with Harper & Row to publish his memoirs. Time Magazine had rights to publish an excerpt from the unreleased manuscript, but before they could, The Nation Magazine got an unauthorized copy and scooped Time. Harper & Row sued The Nation for copyright infringement. Abrams, representing The Nation, argued that their use of the excerpt qualified as fair use. However, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of Harper & Row, saying that using the unpublished material without permission was not fair use, emphasizing the importance of protecting an author's right to control the first public appearance of their work.

United States v. Providence Journal Company

In this case, Abrams was representing a newspaper and its executive editor who had been held in contempt for violating a restraining order prohibiting them from publishing information about a deceased man. The case was ultimately dismissed from the Supreme Court because they felt the contempt order was "transparently invalid" under the First Amendment.

Minnick v. Mississippi

Two men, Robert S. Minnick and James Dyess, escaped from jail and committed a double murder. Minnick was arrested in California and initially refused to speak to the police without a lawyer. However, the sheriff later insisted on questioning him, and Minnick confessed to one of the murders. In a departure from his more typical First Amendment cases, Abrams represented Minnick and argued that questioning Minnick without a lawyer present after he’d requested one was a violation of the Fifth Amendment, which protects against self-incrimination. The Supreme Court ruled in Minnick’s favor, ruling that once someone asks for a lawyer, no more questioning can happen without the lawyer present unless the person voluntarily decides to waive that right.

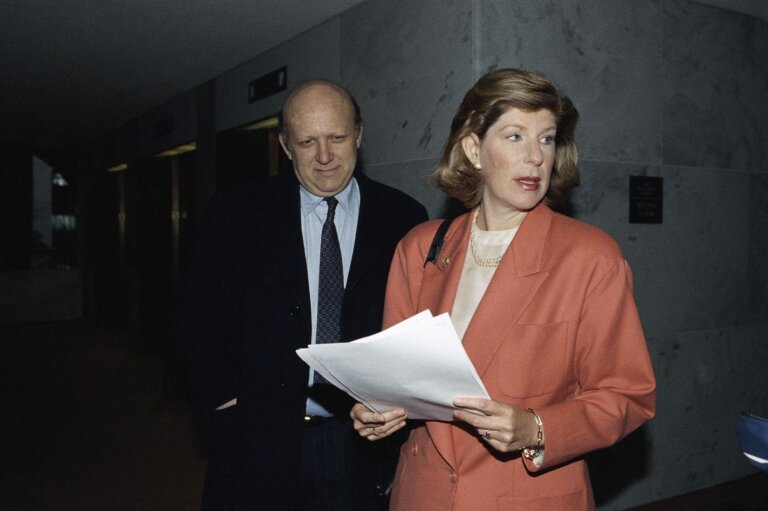

Abrams defended Nina Totenberg and National Public Radio in a senate investigation following Totenberg’s bombshell reporting on Anita Hill’s sexual assault allegations against then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas.

Varity Corporation v. Howe

In another case unrelated to the First Amendment, Abrams represented the Varity Corporation. Employees of the company participated in a self-funded employee welfare benefit plan protected by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). When the company's financial situation worsened, the employees were persuaded to switch to a new plan with promises that their benefits would remain secure. However, they ended up losing their benefits, and they sued the company. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the employees stating that the Varity Corporation violated their fiduciary obligations under ERISA by deliberately misleading the employees.

Abrams successfully defended the Brooklyn Museum against Rudy Giuliani and the City of New York, who threatened to slash the museum's funding for showing an exhibit described as "sick" and "disgusting."

McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (FEC)

In his first of two Supreme Court cases associated with campaign finance, Abrams represented Mitch McConnell to challenge a campaign finance reform law called the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), which banned unrestricted donations to political parties (known as "soft money"), limited advertising by unions, corporations, and non-profit organizations close to elections, and restricted political parties from using their funds for certain ads. Abrams and the McConnell team argued that the ban on "soft money" and the regulations on political advertising infringed on free speech rights and claimed that Congress didn’t have the authority to regulate elections in this way. The Supreme Court mostly upheld the law, disagreeing with Abrams. They said that since the law only restricted “soft money” which is mainly used for registering and getting voters to polls and less for expressing political views, the restrictions on free speech were minimal.

Abrams defended Judith Miller and The New York Times when subpoenaed to reveal confidential sources. Miller ended up spending 85 days in jail for refusing to name her sources to a grand jury.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

In this landmark case, Abrams once again worked with McConnell to ultimately convince The Supreme Court to overrule portions of McConnell v. FEC and other precedents regarding limits on campaign financing. Citizens United initially brought the FEC to court over their film, “Hillary: The Movie,” which expressed opinions about how Hillary Clinton would perform as president, and which the FEC flagged as in violation of the BCRA, which limits campaign financing and political advertising by corporations and other entities. Abrams once again argued that the BCRA violated the First Amendment. This time the Supreme Court agreed, stating that corporate funding of independent political broadcasts couldn't be limited under the First Amendment. This case famously established the precedent that corporate speech is protected by the First Amendment.

Abrams represented facial recognition software company Clearview AI in a series of lawsuits challenging the legality of their work.