In this excerpt from Scout, Atticus, and Boo by Mary Murphy, Murphy uncovers the real life parallels between To Kill a Mockingbird and Harper Lee’s life and investigates Lee’s aversion to being in the public eye. The research for this book became crucial in creating her documentary AMERICAN MASTERS Harper Lee: Hey Boo. Excerpt published compliments of Mary Murphy and Harper Perennial.

“Our National Novel”

Reading To Kill a Mockingbird is something millions of us have in common, yet there is nothing common about the experience. It is usually an extraordinary one. To Kill a Mockingbird leaves a mark. And somehow, it is hermetically sealed in our brains—the memory of it fresh and clear no matter how many decades have passed. If you ask, people will tell you exactly where they were and what was happening to them when they read Harper Lee’s first and only novel. It may be the first “adult” book we read, assigned in eighth or ninth grade. Often it is the first time a young reader is completely kidnapped by a novel, taken on an enthralling ride until the very end. After half a century, To Kill a Mockingbird’s staying power is remarkable: still a best seller, always at the top of lists of readers’ favorites, far and away the most widely read book in high school.

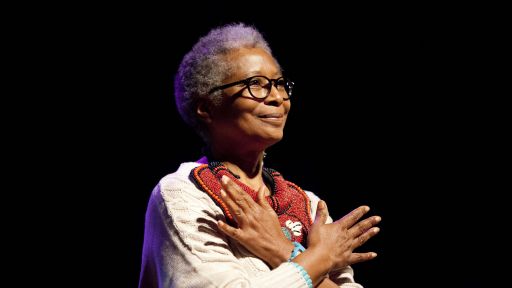

“I think it is our national novel,” Oprah Winfrey told me when I interviewed her for my documentary about To Kill a Mockingbird’s power and influence. “If there was a national novel award, this would be it for the United States. When I opened my school [for girls in South Africa], everybody wanted to know what we can bring and what can we give the girls. I asked everybody to bring their favorite book, and I would say we probably have a hundred copies of this book. Each person who brought the book wrote their own words to the girls about why they believe this book was an important book, and everybody says something different.”

That’s because almost everyone can relate to it—one way or another. Look at all the ground To Kill a Mockingbird covers: childhood, class, citizenship, conscience, race, justice, fatherhood, friendship, love, and loneliness. With all due respect to the wave of social-networking sites, applications, and abbreviations in which we are awash these days, I would like to point out that the community this fifty-year-old novel invites and enjoys is one of the greatest social networks of all time. Try saying “Boo Radley” to the person next to you on the bus. Or say “chiffarobe,” as Mayella Ewell does. Mention Scout, Atticus, Jem, Mrs. Dubose, or Tom Robinson, and see where it takes you. People respond. They connect. Friendships form.

When I met Liz Tirrell, a screenwriter and documentary director, it did not take long to fi nd out she could recite line after line from the book and the movie. We bonded over “Hey, Mr. Cunningham . . . I’m Jean Louise Finch. I go to school with Walter; he’s your boy, ain’t he?”

When Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Diane McWhorter was growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, she and her schoolmates recited the “Hey, Mr. Cunningham” lines and spoke Scout whenever possible. “Cecil Jacobs is a big wet hen,” and “What in the Sam Hill are you doing?” and other imitations rang out at recess.

Anna Quindlen, the Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist and novelist, said she simply could not be friends with anyone who does not “get” Scout. “I remember someone telling me that they thought Scout was a peripheral character, and I was shocked out of my skin.”

But then, I have another friend, a novelist who teaches fiction writing, who told me that when she mentioned To Kill a Mockingbird as a favorite, a fellow professor said, “We don’t consider that literature here.”

Really?

“You Have Another Think Coming”

That pronouncement sent me right back to the novel. And unlike other favorites from childhood, another reading of To Kill a Mockingbird rewards and reaffi rms. The story is as rich as the Alabama soil it comes from; its veins can be mined over and over again. If you think you cannot go back to it and fi nd more, “You have another think coming,” as Scout Finch would say.

My second reading of To Kill a Mockingbird was a revelation. It felt as though I was reading it for the very fi rst time. How could I have forgotten Calpurnia and “It’s not necessary to tell all you know”? Or Dolphus Raymond, the drunk, who was not a drunk at all? Or all the history? And the writing. The writing! The economy was dazzling. My enthusiasm was unbridled, my appreciation immense.

Looking back, I see that the fi rst time, I was blinded by love. For Scout: funny, smart, overall-wearing, fists-flying, lynch-mobscattering Scout. Scout knew who she was, and she had the greatest father on the planet.

Here she was again—only better.

On her cousin: “Talking to Francis gave me the sensation of settling slowly to the bottom of the ocean. He was the most boring child I ever met.”

On the neighbors: “The Radley Place was inhabited by an unknown entity the mere description of whom was enough to make us behave for days on end; Mrs. Dubose was plain hell.”

On her father: “Atticus was feeble: he was nearly fifty.”

On the caste system in her town: “. . . to my mind it worked this way: the older citizens, the present generation of people who had lived side by side for years and years, were utterly predictable to one another: they took for granted attitudes, character shadings, even gestures, as having been repeated in each generation and refined by time. Thus the dicta No Crawford Minds His Own Business, Every Third Merriweather Is Morbid, The Truth Is Not in the Delafields, All the Bufords Walk Like That, were simply guides to daily living.”

After I finished, I carried my paperback copy of To Kill a Mockingbird around with me for weeks. I needed to stay in its thrall. I read random pages, sometimes aloud, and was instantly reinvigorated.

Novelist Mark Childress, who wrote Crazy in Alabama, told me he reads To Kill a Mockingbird “as a refresher course” almost every year. “Every time I go back, I’m impressed more by the simplicity of the prose. . . . Although it’s plainly written from the point of view of an adult, looking back through a child’s eyes, there’s something beautifully innocent about the point of view, and yet it’s very wise.”

Allan Gurganus, author of The Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All and other novels, said of his rereading: “What’s marvelous is that you see that sometimes the fi rst things that happen to you are as big as they seemed. And, it’s very moving to see what an evergreen and enduring achievement it’s truly turned out to be.”

“As Relevant Today as the Day It Was Written”

My second reading of To Kill a Mockingbird was fifteen years ago. And then, like Scout, I decided to go exploring. I began looking into the novel’s history, stature, and popularity. By any measure, it is an astonishing phenomenon. An instant best seller, winner of the Pulitzer Prize, a screen adaptation ranked one of the best of all time. Fifty years after its publication, it sells nearly a million copies every year—hundreds of thousands more than The Catcher in Rye, The Great Gatsby, or Of Mice and Men, American classics that also are staples of high school classrooms.

No other twentieth-century American novel is more widely read. Even British librarians, who were polled in 2006 and asked, “Which book should every adult read before they die?” voted To Kill a Mockingbird number one. The Bible was number two. Why? What is it about this novel, I asked everyone I interviewed. “I think people want to read something substantial,” answered novelist Lee Smith, author of The Last Girls and eleven other books. “They want to have something to believe in, and To Kill a Mockingbird manages to do that without being too preachy.”

Until she retired from North Carolina State University, Smith taught To Kill a Mockingbird for twenty-five years. “Students are reading it today with the same responses we all had in the sixties,” she said. “It still has a galvanizing effect on a young reader. This is a novel which endures, as opposed to other classics which don’t appeal as much to readers today. The Sun Also Rises is a good example, because students just say, ‘Who are all these people drinking in Spain? What is this about?’ You never get that reaction to To Kill a Mockingbird. It remains as relevant today as it was the day it was written. It never ages. It’s a story of maturing, certainly, and initiation, but told in such beautifully specific terms that it never seems generic.”

Novelist Wally Lamb, author of I Know This Much Is True and The Hour I First Believed, told me he did not enjoy reading in high school. Then he found To Kill a Mockingbird in his sister’s room. “I flipped it open and read the first couple of sentences and . . . two days later I, the pokiest reader I knew, had finished the book. It was the first time in my life that a book had captured me. That was exciting. I didn’t realize that literature could do that.” And when Lamb went on to teach high school in Connecticut, he saw his students respond the same way. “It was a book they read because they wanted to, not because they had to. It cast the same spell for my students as it had for me.”

Winfrey was a young girl living with her mother in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, when a librarian recommended To Kill a Mockingbird. She remembered “just devouring it,” and climbing right aboard the Scout bandwagon. “I wanted to be Scout, I thought I was Scout. I wanted an accent like Scout and a father like Atticus.”

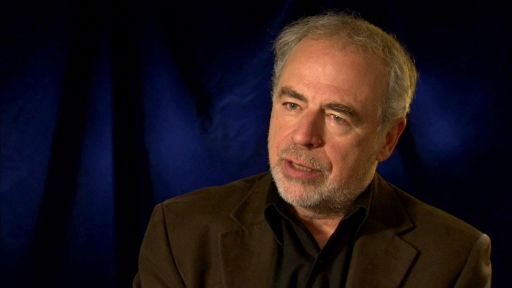

Who doesn’t want a father like Atticus? Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Richard Russo did. “Atticus Finch was the father maybe that I longed for,” he said.

Beyond being an ideal father, Atticus Finch is a folk hero to lawyers. When Scott Turow, a lawyer who became famous for writing novels about lawyers, read To Kill a Mockingbird as a student in Chicago, “I promised myself that when I grew up and I was a man, I would try to do things just as good and noble as what Atticus had done for Tom Robinson.”

Lest we forget, Atticus also is the best shot in the county. An understanding single father, an honest and humble lawyer, a respectful neighbor, Atticus is a paragon but never a caricature. “People want to believe in an idealized world, and that has an instructive moral function,” Turow said. “It’s true that there aren’t many human beings in the world like Atticus Finch—perhaps none—but that doesn’t mean that it’s not worth striving to be like him.”

Boo Radley loomed large in all my conversations. The house, and the mystery and suspense built up around it, was familiar territory.

“Boo Radley cannot be overestimated as an important factor in this book,” Smith said. “Every neighborhood has that house that’s overgrown and those neighbors that are weird or that you never ever, ever see. And stories grow up about them. That figure always occupies a place in a child’s imagination. And to demystify that—to make us see that people so radically different from us are OK, and can be helpful and wonderful—this is so important.”

“Boo Radley is now a phrase in the language, [as in] the block’s Boo Radley,” said Gurganus. “Many people who haven’t read To Kill a Mockingbird have that phrase in their lingo.” Indeed, Boo Radley has entered not only our vernacular but also our yellow pages. Novelty stores, bars, and antiques dealers bear his name: Boo Radley’s Store in Spokane; Boo Radley’s Bar in Mobile, Boo Radley’s Antiques in Los Angeles.

“I Am Alive, Although Very Quiet”—Harper Lee

All of this despite an author who has done nothing to publicize her book for more than forty-five years. In 1993, Harper Lee wrote to her agent, “Although Mockingbird will be thirty-three this year, it has never been out of print and I am still alive, although very quiet.” The same can be said seventeen years later. Still among us, at eighty-four, Nelle Harper Lee, who dropped her first name when she published, was born in the small town of Monroeville, Alabama, and moved to New York around 1948. She has divided her time between the two cities ever since. In 1964, Lee gave an interview to Roy Newquist of WQXR, a New York radio station, and said she was working on a second novel “and it goes slowly, ever so slowly.” Since then, she has not given another full interview or published another book, only adding to her mystique.

Reverend Thomas Lane Butts, the former pastor of Monroeville’s First United Methodist Church, has been a friend of Lee’s for more than twenty-fi ve years. “Being famous and a celebrity is probably a lot of fun the fi rst two or three months, but after you’ve been a celebrity for fi fty years it gets old, I’m quite sure,” he said. “She has controlled her own destiny. She doesn’t have a PR person. She doesn’t need one. I think she has led a happier life and certainly [a] more contented life because she has chosen how she has related to the public.”

“It takes a kind of courage that almost nobody has in this country, where celebrity has replaced religion for a lot of people, to turn away from the church of publicity and say, ‘I’m not going to pray there, I’m not going to appear there,’ ” Mark Childress said. “It’s a kind of blasphemy in this society that she commits by refusing to participate in the publicity machine. ”

Occasionally, Lee has made public appearances, usually to pick up awards. In 2007, she was at the White House to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Her picture has been taken, but she does not speak to the press. “A lot of people think that she’s a recluse,” said Reverend Butts, “and that is absolutely untrue. She’s a person who enjoys her privacy like any other citizen would.”

Albeit a citizen who wrote a book that has made—and continues to make—a difference to generations of readers. Oprah Winfrey once met Harper Lee for lunch in New York, hoping to coax the author onto her talk show. “I knew twenty minutes into the conversation that I would never be able to convince her to do an interview,” she recalled. Nevertheless, “we were like instant girlfriends,” she said. “It was just wonderful, and I loved being with her.”

Harper Lee, flanked by C-SPAN founder Brian Lamb and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the president of Liberia, recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, November 5, 2007

In 2002, Jon Meacham, the editor of Newsweek and Pulitzer Prize–winning biographer of Andrew Jackson, had a chance to talk with Lee when she accepted an honorary degree at the University of the South, in Sewanee, Tennessee, Meacham’s alma mater. “I found her to be completely unassuming,” he said, “and therefore all the more powerful for it.”

Reading Aloud

When I began filming interviews with writers and readers, I asked everyone to read aloud a favorite passage from the novel. In twenty-six interviews, only two passages were chosen more than once. Reverend Butts, Childress, Meacham, and Winfrey all chose the passage in which Atticus leaves the courtroom. He has lost the case but is honored in defeat by the black community relegated to the balcony. Scout is among them, and Reverend Sykes instructs her, “Miss Jean Louise, stand up. Your father’s passing.”

As she read, Oprah had tears in her eyes.

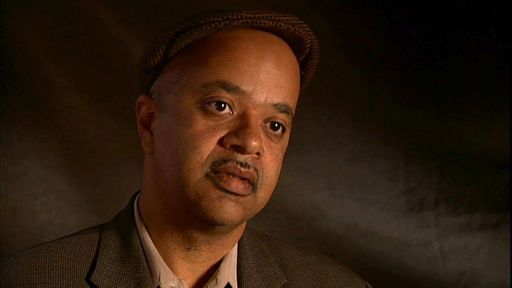

James McBride, the memoirist and novelist, and Rick Bragg, a Pulitzer Prize–winning reporter and memoirist, chose to read from the book’s beginning:

When he was nearly thirteen, my brother Jem got his arm badly broken at the elbow. When it healed, and Jem’s fears of never being able to play football were assuaged, he was seldom self-conscious about his injury. His left arm was somewhat shorter than his right; when he stood or walked, the back of his hand was at right angles to his body, his thumb parallel to his thigh. He couldn’t have cared less, so long as he could pass and punt.

When enough years had gone by to enable us to look back on them, we sometimes discussed the events leading up to his accident. I maintain that the Ewells started it all, but Jem, who was four years my senior, said it started long before that. He said it began the summer Dill came to us, when Dill first gave us the idea of making Boo Radley come out.

McBride told me he read that passage repeatedly when he was writing his memoir, The Color of Water: A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother. “This paragraph sets up the whole book,” he said of Lee’s opening. “It sets up the whole story. By speaking to the specific, the story of how her brother broke his arm, she speaks to the general problem of four hundred years of racism, slavery, socioeconomic classism, problems between classes, problems between people who have, people who don’t, the courage of the working class, the isolation of the South, the identity crises of a young girl, and the coming out of a neighborhood recluse. All that in the story of her brother, who, when he was nearly thirteen, broke his arm.”

McBride’s memoir began, “When I was fourteen, my mother took up two new hobbies: riding a bicycle and playing the piano.” I read that as an homage to the first sentence of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Bragg, who wrote All Over but the Shoutin’, a tribute to his mother, grew up dirt-poor in Possum Trout, a tiny community in northern Alabama. He zeroed in on Lee’s sentence “I maintain that the Ewells started it all, but Jem, who was four years my senior, said it started long before that.” Bragg said, “Southern writers are always saying stuff to be profound, like that’s a quintessentially Southern phrase. But the truth is, down here, everything started long before that. That’s just the way it is.”

Deeper Truths

Each time another person agreed to be interviewed, I wondered if there was anything new to be said. Invariably, there was.

“Stories that deal with injustice are really powerful [in America],” suggested novelist James Patterson, who lists To Kill a Mockingbird as one of the only two books he enjoyed reading during high school in Newburgh, New York. “I think we have more of a sense of that than they do in some places where injustice is more a fact of life.”

Rosanne Cash, the singer/songwriter and memoirist, thought the novel should be read as a parenting manual: “There’s just this beautiful naturalness that [Atticus] has and sense of confidence in his own skill as a parent. And respect for the child, that mutual respect.”

To Kill a Mockingbird’s small-town setting is what stuck with NBC’s Tom Brokaw, who grew up in small towns throughout South Dakota and knew “not just the pressures that [Atticus] was under, but the magnifying glass that he lived in. This all takes place in a very small environment. People who live in big cities don’t have any idea of what the pressures can be like in a small town when there’s something controversial going on.”

When Allan Gurganus read To Kill a Mockingbird, he “felt the permission to write about small-town life and the permission to feel that huge international drama, all the circumstances of truth, justice, and the American way, could be played out in a town of two thousand souls and could be played out by a single just man who stands up to be counted.”

Meacham was impressed by the “moral ambiguity” of the novel’s ending. “I think the courageous thing that Miss Lee did was end it on a tragic note. You would think in a novel like this, that’s achieved this kind of status, it would be a very melodramatic tale of good and evil. Instead, it’s a tale of good and evil that ends on a note of gray, which is where most of us live.”

Historian McWhorter, who wrote Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama: The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution, said, “For a white person from the South to write a book like this in the late 1950s is really unusual—by its very existence an act of protest.”

“It was an act of protest, but it was an act of humanity,” said Andrew Young, the former UN ambassador, mayor of Atlanta, and veteran of the civil rights movement, who worked with Martin Luther King. “It was saying that we’re not all like this. There are people who rise above their prejudices and even above the law.”

Anna Quindlen, Lee Smith, and Adriana Trigiani, the novelist whose Big Stone Gap books are set in her Virginia hometown, all sang Scout’s praises, each in a different verse. So did Lizzie Skurnick, who blogs about young adult books for Jezebel.com and is the author of Shelf Discovery: The Teen Classics We Never Stopped Reading, and David Kipen, former director of literature for the National Endowment for the Arts and supervisor of the NEA’s Big Read program, which includes To Kill a Mockingbird.

I don’t really give a rip about Atticus. He is fine, and he is a terrific dad. For me, this book is all about Scout. And I don’t really care about anybody else in the book that much, except to the extent that they are nice to Scout and make life easier for Scout. —Anna Quindlen

Here’s Scout, who believes in things, who is funny and curious and passionate and a tomboy. I think Scout has done more for Southern womanhood than any other character in literature. —Lee Smith

I craved the kind of life [Scout] had. She seemed to me to be fiercely independent; there seemed to be a streak of Pippi Longstocking in her, like she owned the town, and that appealed to me. — Adriana Trigiani

Scout struggles with things in a very genuine way. The second half of the novel, those grand themes of justice, injustice, those are about how the world acts on us. But Scout is really about who we are in the world, how we decide that. —Lizzie Skurnick

She’s a scamp and hysterically funny, and no less funny as an adult looking back, although in a slightly more fermented and seasoned way. She’s just great company. —David Kipen

Richard Russo realized that the relationship between Scout and Atticus was burrowed deep within him. “It aided me in writing all of my father/daughter stuff, all my family stuff, because that is a quintessential American family, even though it’s not typical.”

As a young boy, Mark Childress read the novel on a porch in Monroeville, Alabama, where he, like Harper Lee, was born. “That was the first adult novel that I had ever read, and I was just about the age of Scout when I read it, and I was reading it in the setting where it happened. And it’s the reason I’m a writer today. Something about seeing that ugly little town, which at that point had been sort of stripped of all of its charms, transformed into this magical thing that was in my hands.”

Wally Lamb found To Kill a Mockingbird to be “a great course in how to write a novel.” He pointed to Lee’s “gorgeous” description of the town:

Maycomb was an old town, but it was a tired old town when I first knew it. In rainy weather the streets turned to red slop; grass grew on the sidewalks, the courthouse sagged in the square. Somehow it was hotter then: a black dog suffered on a summer’s day; bony mules hitched to Hoover carts flicked flies in the sweltering shade of the live oaks on the square. Men’s stiff collars wilted by nine in the morning. Ladies bathed before noon, after their three-o’clock naps, and by nightfall were like soft teacakes with frostings of sweat and sweet talcum.

Lamb said, “It is a one-paragraph course on writing, those tactile sensations, that’s real writing. That’s literature.”

The “literature” question came up again, this time in the pages of the New Yorker in May 2006. In his review of Mockingbird, an unauthorized biography of Harper Lee by Charles Shields, Thomas Mallon dismissed Atticus as “a plaster saint” and Scout as “a highly constructed doll, feisty and cute on every subject from algebra to grown-ups.” Mallon allowed that, “Indisputably, much in the novel works,” but complained of “occasionally clumsy sentences,” and also wrote that Horton Foote’s screen adaptation was “rather better than the original material.”

When I asked McWhorter about Mallon’s essay, she responded directly to Mallon. “How many cities have read your books?” she asked.

McBride was even more exercised about Mallon’s criticism. “Whoever this guy is, whatever this schmoo is, they’re not going to be reading his book in fifty years. People are going to be reading Harper Lee in this country as long as they draw oxygen. It is a great book now, it was a great book yesterday, and it will be a great book tomorrow.”

Scott Turow was perplexed. “I just think the grace of the writing is substantial, and I am confounded by people who attack it as a work of literature. I think it is a beautifully written and structured book. Is it sentimental? Yes, it’s sentimental, but so was Steinbeck, and people still read Steinbeck.”

Russo, a former professor at Colby College in Waterville, Maine, offered, “Back when I was teaching, I use to remind my students that masterpieces are masterpieces not because they are flawless but because they’ve tapped into something essential to us, at the heart of who we are and how we live.”

By the time Mallon was asked if he would discuss any of this with me, his hate mail had piled up considerably. He said no, he was not going to be the skunk at that garden party.

The Finches of Maycomb; The Lees of Monroeville

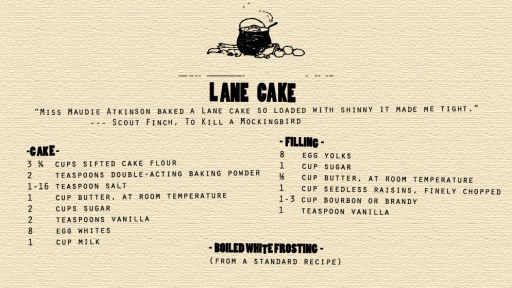

That garden party will go forever in To Kill a Mockingbird’s Maycomb, where Mrs. Dubose’s camellias are in bloom, Miss Maudie’s mimosas are as fragrant as ever, and wisteria drips all over the porch. Children roam freely, dewberry tarts are served, and aprons are starched. Confederate pistols are hidden, schools and churches are segregated, and Sundays are for visiting. The fictional Maycomb bears more than a passing resemblance to the landscape of the town where the novelist grew up during the Depression. “Monroevillians who read the book will see familiar names. Some events and situations are tinged with local color,” said an editorial in the Monroe Journal in June 1960.

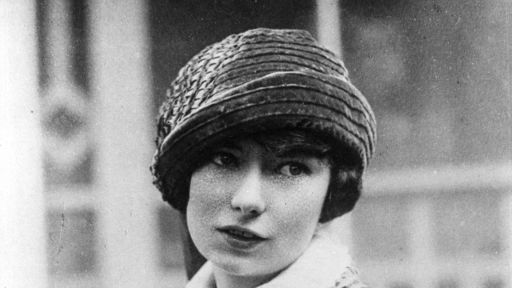

Harper Lee poses for Life magazine in the balcony of the old courthouse in Monroeville, Alabama, May 1961.

Monroeville is set on a square with a courthouse in the middle. That is where Harper Lee has said that she, as Scout did in the novel, spent time in the balcony watching her own lawyer father, Amasa Coleman Lee (often called A.C.) at work. “Few people live to be 80 years old and then have their name changed,” the Journal reported, “that is what has happened to a prominent Monroeville attorney. A. C. Lee is now being called Atticus Finch.” Finch was the maiden name of A.C.’s wife and Harper Lee’s mother, Frances.

In 1961, when she was photographed in the balcony of the Monroe County Courthouse by Life, Lee told the magazine, “The trial was a composite of all the trials in the world—some in the South. But the courthouse was this one. My father was a lawyer, so I grew up in this room and mostly watched him from here. My father is one of the few men I’ve known with genuine humility, and it lends him a natural dignity. He has absolutely no ego drive, and so he was one of the most beloved men in this part of the state.”

While Nelle Harper Lee was growing up, her lawyer father also was a state legislator (1926–1938) and the editor of the Monroe Journal (1929–1947). This was the Deep South, where cotton was plentiful and sharecropping the norm. Monroeville was a farming community, hard-hit during the Depression. The Hoover carts of Maycomb—mules or oxen hitched to a car because gasoline was unaffordable—were on the real-life streets of Monroeville.

The Monroe Journal of the thirties includes reports of a black man accused of raping a white woman, rabid-dog warnings, and ads for V. J. Elmore’s, the variety store where Jem buys Scout her sequined baton in the novel. Monroeville residents remember a boy who lived in a ramshackle house near the school who was not allowed out after a run-in with the law and a schoolyard rumor that the pecans from the trees at that house were poisoned, as was said of Boo Radley’s house. And a girl dressed up as a ham for an agricultural pageant as Scout did for the Halloween play.

The former courthouse, now the Monroe County Heritage Museum.

Connecting real people, places, and events to those in the novel is a favorite pastime for residents. It fuels tourism. The old courthouse where A. C. Lee once worked is now the Monroe County Heritage Museum, a monument to To Kill a Mockingbird and the town it comes from. One room is set aside for Truman Capote, the author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood, who was raised mainly in Monroeville by his mother’s relatives until he was nine. In a display case is Capote’s baby blanket and a colorful coat worn by an aunt. The museum gets twenty thousand visitors a year, says its director, Jane Ellen Clark. “We just try to answer their questions about the book, and about the town. Because everybody wants to know what was real and what wasn’t. Everything that I see or hear in the book I can relate to some thing [in Monroeville]. I do think that she was talking about her town, and her family, and all the people that she knew here.”

Miss Alice Remembers

The novelist’s older sister Alice Finch Lee sees it differently. “Nelle Harper says that everybody around Monroeville was determined to see themselves in the book. They would come up to her and say, ‘I’m so and so in the book.’ But we learned that wherever they were, they placed the book setting where they lived. Early on, Nelle Harper got a letter from a young woman in Chicago who was a doctor, and she said, ‘I’m interested to know when you spent so much time in Greensboro.’ Now, the only time Nelle Harper ever been to Greensboro was when she passed through it to go to school.”

At the age of ninety-eight, Alice Finch Lee can still be found at her desk every day at Barnett, Bugg and Lee, the Monroeville law firm where her father worked. Alice Lee handles real estate transfers and titles when not politely declining interview requests of her sister or sorting through the boxes of fan mail.

Amasa Coleman Lee, Harper Lee’s father.

“Everyone tries to make it an autobiography or a biography or a true story,” she said to me a bit wearily. Unlike the fictional Finches, “we had a mother, we loved both parents.” Frances Finch Lee, a talented musician, lived until 1951. Nelle Harper was twenty-five and Alice forty when she died.

Alice Lee described her sister as a tomboy and a gifted storyteller who had a vivid imagination all her life. “At home we were pretty much allowed to go in the direction we wanted to go, unless we were headed the wrong way. But we knew we were expected to go to Sunday school and church on Sunday, which we did. We knew we had to go to school through the week. But we were pretty much left on our resources for entertainment. Nelle Harper was very athletic. She liked to play with the little boys more than the little girls because she liked to play ball.”

Nelle and Truman; Scout and Dill

Frances Finch Lee, Harper Lee’s mother.

One of those little boys lived next door to the Lees: Truman Streckfus Persons, who later took his stepfather’s name and became Truman Capote. In the novel, Dill Harris lives with his aunt Rachel next door to the Finches; he is the only character that Harper Lee has acknowledged had a model from real life. Capote based Idabel Tompkins, a character in Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) on Lee. In Capote’s novel, Idabel says, “Hell, I’ve fooled around with nobody but boys since first grade. I never think like I’m a girl, you’ve got to remember that or we can never be friends.” That these childhood playmates from a tiny town, who once shared a beat-up old Underwood typewriter Mr. Lee brought home from the newspaper, would go on to write American classics both captures and boggles the imagination.

In 1959, when To Kill a Mockingbird was finished but not yet published, Lee went to Holcomb, Kansas, to work on what Capote called his nonfiction novel, about the murder of a farm family. Those reporting trips became the subject of two movies Capote (2005) and Infamous (2006), and twined the two together in popular culture. By the time the movies about him appeared, Capote had been dead for more than twenty years. Lee was nearly eighty.

The childhood friendship would not survive. According to Alice Lee, Capote’s envy over To Kill a Mockingbird winning the Pulitzer Prize consumed him. “Truman became very jealous because Nelle Harper got a Pulitzer and he did not. He expected In Cold Blood to bring him one, and he got involved with the drugs and heavy drinking and all. And that was it. It was not Nelle Harper dropping him. It was Truman going away from her.”

In time, a persistent and untraceable rumor developed, largely fueled by the fact that Lee did not publish a second book, which suggested Capote had something to do with the writing of To Kill a Mockingbird. Many of the writers I interviewed rejected this notion based on style alone. Mark Childress said, “I got a letter from Harper Lee one time that absolutely proved to me that she wrote every word of To Kill a Mockingbird ’cause the voice is completely the voice of the book. It’s the most beautifully, eloquently written letter. So I know that people are lying when they say that.”

Young Truman Capote with his aunt in Monroeville, Alabama.

Anna Quindlan said, “Truman Capote would have ginned up all kinds of scenes in that book. You know, just by reading To Kill a Mockingbird, that Harper Lee, who is obviously Scout, is a person with a grounded self-esteem, surrounded by affection. Whereas you have that horrible moment where her hideous second cousin Francis, the one that she beats up and calls a whore lady with no idea what that means, says something terrible about Dill, who is based on the boy Truman Capote. He says, ‘[Dill] doesn’t come to visit you in the summer. His mother doesn’t want him and she passes him around from person to person’ and you think, oh that little boy is going to be in real trouble and, of course, that little boy was.”

When a Thing like This Happens to a Country Girl Going to New York

“It was somewhat of a surprise and it’s very rare indeed when a thing like this happens to a country girl going to New York,” A. C. Lee told his local paper in 1960.

Very rare indeed. Nelle Harper left the University of Alabama in 1948, one semester short of completing her law studies, and moved to New York to pursue writing. She supported herself as an airline ticket agent until friends, Michael and Joy Brown, gave her an unusual present on Christmas Day, 1956: the money to quit her job and write full-time for one year. “Their ‘faith in me’ was really all I heard them say,” Lee wrote later, in a 1964 essay for McCall’s magazine. “I would do my best not to fail them.”

And so she did. By June 1957, Nelle Harper Lee had an agent and a manuscript, titled “Atticus,” that was submitted to the publisher J. B. Lippincott Company. “There were many things wrong about it,” editor Tay Hohoff later recalled. “It was more of a collection of short stories than a true novel. And—and yet, there was also life. It was real. The people walked solidly onto the pages; they could be seen and felt. . . . Obviously a keen and witty and even wise mind was at work; but was it the mind of a professional novelist? There were dangling threads of a plot, there was a lack of unity—a beginning, a middle, and an end—that was inherent in the beginning. It is an indication of how seriously we were impressed by the author that we signed a contract at that point.” Hohoff described the prepublication life of the novel in “We Get a New Author,” an essay for the Literary Guild’s magazine to promote the selection of To Kill a Mockingbird as its book of the month.

After the book contract was signed, two more years of work followed—“a long and hopeless period of writing the book over and over again” is how Lee described it to the New York Times in 1961—though there is no record to be found of the edits that were made to the manuscript. The Christmas gift from her good friends and a small advance from her publisher could only stretch so far. “It’s no secret,” Hohoff wrote in 1967, “that she was living on next to nothing and in considerable physical discomfort while she was writing Mockingbird. I don’t think anyone, certainly not I, ever heard one small mutter of discontent throughout all those months of writing and tearing up, writing and tearing up.”

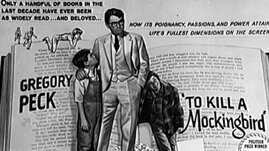

The end result was a triumph. Even before its official publication date, To Kill a Mockingbird had begun to soar. It was chosen for the Literary Guild and to be condensed for the Reader’s Digest Book Club. “Harper Lee’s first novel sets the whole book world on fire! The reason: It makes you so glad to be alive,” blared the publisher’s ad for the $3.95 hardcover. “Weeks before publication the book world was talking about To Kill a Mockingbird. The grapevine began humming with excitement. Booksellers heard it and increased their advance orders.”

Summer of ’60

To Kill a Mockingbird was published on July 11, 1960. It was the summer the birth-control pill was released, Elvis Presley returned to civilian life and recorded “It’s Now or Never,” some seven hundred U.S. military advisers were in South Vietnam, Psycho was in movie theaters, Gunsmoke was on TV, the Kennedy-Nixon campaign was just beginning, Wilma Rudolph won threegold medals at the summer Olympics in Rome, and Alan Drury’s Advise and Consent, a novel about a secretary-of-state nominee who once had ties to the Communist Party, was at the top of the bestselling fiction list. Better Homes and Gardens First Aid for Your Family was moving quickly to the top of the nonfiction list.

That summer, most forms of racial segregation were not yet against the law, and civil disobedience, such as sit-ins at lunch counters, had only just begun. “People forget how divided this country was,” Scott Turow said, “what the animosity was to the Civil Rights Act, which probably never would have been passed if John F. Kennedy hadn’t been assassinated, and it became his legacy. But that was 1963. In 1960 there were no laws guaranteeing that African Americans could enter any restaurant, any hotel. We didn’t have those laws. In that world, [for Harper Lee] to speak out this way was remarkable.”

In Alabama only sixty-six thousand of the state’s nearly one million blacks were registered to vote. Three years later, in his 1963 inauguration speech, Governor George Wallace vowed, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.” Six months after his inauguration, Wallace stood in the schoolhouse door refusing to integrate the University of Alabama.

In Birmingham, where the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church that killed four young girls would become a turning point in the civil rights movement, Andrew Young was working on the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s campaign to desegregate the downtown businesses. “You had, for the fi rst time, black people making union wages in the steel mills,” he remembered. “And they began to build nice homes. These were veterans of ser vice in the military who came back, went to school, got good jobs, and started building nice little homes, nothing fancy, just little three-bedroom frame houses. There were more than sixty of those houses dynamited [by whites in the late fifties]. To Kill a Mockingbird gave us the background to that, but it also gave us hope that justice could prevail. I think that’s one of the things that makes it a great story, because it can be repeated in many different ways.”

Childress recalled the story of how Abraham Lincoln greeted Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in 1862. President Lincoln reportedly said, “So this is the little lady who started our big war.” Childress said, “I think the same can be said of Harper Lee. This was one of the most influential novels, not necessarily in a literary sense, but in a social sense. It gives white Southerners a way to understand the racism that they’ve been brought up with and to find another way. And for white Southerners at that time, there was no other way. And most white people in the South were good people. Most white people in the South were not throwing bombs and causing havoc. But they had been raised in the system, and I think the book really helped them come to understand what was wrong with the system in the way that any number of treatises could never do, because it was popular art, because it was told from a child’s point of view.”

Rick Bragg saw the novel’s impact on whites, on “young men who grew up on the wrong side of the issue that dominates this book. They start reading it, and the next thing you know, it’s not just held their interest, it’s changed their views. That’s almost impossible. But it happens.”

One of the reasons it can happen, McWhorter suggested, is that “even though To Kill a Mockingbird is such a classic indictment of racism, it’s not really an indictment of the racist, because there’s this recognition that those attitudes were ‘normal’ then. For someone to rebel and stand up against them was exceptional, and Atticus doesn’t take that much pride in doing so, just as he would have preferred not to have to be the one to shoot the mad dog. He simply does what he must do and doesn’t make a big deal about it.”

Hollywood

“The big danger in making a movie of To Kill a Mockingbird,” its director, Robert Mulligan, said to the New York Times in 1961, “is in thinking of this as a chance to jump on a segregation-integration soapbox. This book does not make speeches. It is not melodramatic, with race riots and race hatred. It deals with bigotry, lack of understanding, and rigid social patterns of a small Southern town.” Mulligan and producer Alan Pakula first approached Harper Lee to write the screenplay. She declined, wanting to work instead on her next book. Texas playwright Horton Foote wrote what many consider to be one of the greatest screen adaptations of all time. The script, faithful to the novel, condensed the time period from three years to one, deleted many characters, and focused heavily on the mystery of Boo Radley and the trial of Tom Robinson.

“Horton Foote was the perfect person to adapt Harper Lee’s book,” said theatrical agent Boaty Boatwright, who cast the children in the movie. “He was a poet and he understood those people and he wrote so beautifully. She and Horton became the closest and the best of friends and stayed completely in touch until [Foote died in 2009]. There are many great books that don’t make great films. And sometimes there are rather bad books that make good films. But this was a real combination. Harper loved what he did; we all did.”

Mary Badham as Scout in the film of To Kill a Mockingbird

To Kill a Mockingbird, starring Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch and featuring Robert Duvall’s wordless screen debut as Boo Radley, was released on Christmas Day, 1962. The opening credit sequence—with Steven Frankfurt’s design of marbles, toys, and crayon drawings and composer Elmer Bernstein’s plaintive piano notes, just the way a child would play them—stands alone.

Young Mary Badham makes a perfect Scout entrance swinging into frame on a Tarzan rope tied to a tree and dropping down. The casting was “pure genius,” wrote Leo Sullivan in the Washington Post, calling the film “an unforgettable beautiful experience.” Bosley Crowther in the New York Times also noted the “superb discoveries” of Badham and Phillip Alford, who played Jem.

“I know authors are supposed to knock Hollywood and complain about how their works are treated,” Harper Lee told Bob Thomas of the Associated Press, “but I just can’t manage it.” In Birmingham, McWhorter was in the fifth grade at the private, all-white Brooke Hill School for Girls with Mary Badham, who, at age nine, with no acting experience, got the part of Scout in the movie. The entire class watched it together. “Every Southern child has an episode of cognitive dissonance having to do with race, and it’s when the beliefs that you held are suddenly contradicted. For me, it was seeing that movie. I remember watching it, fi rst assuming that Atticus was going to get Tom Robinson off because Tom Robinson was innocent, and Atticus was played by Gregory Peck, and of course he’s going to win. Then, as it dawned on me that it wasn’t going to happen, I started getting upset about that. Then I started getting really upset about being upset. By rooting for a black man, you are kind of betraying every principle that you had been raised to believe. And I remember thinking, What would my father think, if he saw me fighting back these tears when Tom Robinson gets shot? It was a really disturbing experience. Crying tears for a black man was so taboo.”

The movie amplified the novel’s importance, and the two—a masterpiece in each medium—are anomalies together.

To Kill a Mockingbird received eight Academy Award nominations and forty-eight years later has the same staying power as the novel. In the last twenty years, the film has appeared on various American Film Institute lists: It was number two on the Best American Films of All Time list of 2006 (It’s a Wonderful Life was number one), and Atticus Finch was the number one Greatest Movie Hero of the 20th Century in 2003.

“You don’t get a chance to have a film and a book that makes that kind of impact,” said Badham, who made two more movies and retired from acting at fourteen. “This is not a black-andwhite 1930s issue. Racism and bigotry haven’t gone anywhere, ignorance hasn’t gone anywhere.”

“A Reminder to the People at Home”

By March 1963, when Harper Lee turned up in Chicago to give a press conference about the film, the civil rights movement had entered the national consciousness. Times had clearly changed, as evidenced by the questions the young novelist was asked. Rogue, a men’s magazine along the lines of Playboy and Esquire, covered the press conference. “What follows is an account of the flood of questions the noted writer must endure, all in the name of publicity,” read the story, which added character descriptions and stage directions to go with dialogue.

“Harper Lee arrived. She is 36-years-old, tall, and a few pounds on the wrong side of Metrecal [a popular diet drink]. She has dark, short-cut, uncurled hair; bright, twinkling eyes; a gracious manner; and Mint Julep diction.”

Reporter: Have you seen the movie?

Miss Lee: Yes. Six times. (It was soon learned that she feels the film did justice to the book, and though she did not have script approval, she enjoyed the celluloid treatment with “unbridled pleasure.”)

Reporter: What’s going to happen when it’s shown in the South?

Miss Lee: I don’t know. But I wondered the same thing when the book was published. But the publisher said not to worry, because no one can read down there.

PR Man: It opened in Florida—

Miss Lee: Phil, honey—that’s not the South.

Reporter: When you wrote the book, did you hold yourself back?

Miss Lee (patiently): Well, sir, in the book I tried to give a sense of proportion to life in the South, that there isn’t a lynching before every breakfast. I think that Southerners react with the same kind of horror as other people do about the injustice in their land. In Mississippi, people were so revolted by what happened, they were so stunned, I don’t think it will happen again.

Reporter: What do you think of the Freedom Riders [the civil rights activists who rode buses into the segregated South to challenge the law]?

Miss Lee: I don’t think much of this business of getting on buses and flaunting [sic] state laws does much of anything. Except getting a lot of publicity and violence. I think Reverend King and the NAACP are going about it exactly the right way. The people in the South may not like it but they respect it.

Reporter (cub variety): I came in late so maybe you’ve already been asked this question, but I’d like to know if your book is an indictment against a group in society.

Miss Lee (nonplussed): The book is not an indictment so much as a plea for something, a reminder to people at home.

The people at home may not have been Lee’s best audience, initially. As Rick Bragg said, “I think it was one of those books where the people down the road might shoot you a dirty look or say mean things about you as the car rolls by, but people a thousand miles away love you and admire you and think that you’ve done something decent and grand.”

Monroeville was segregated; its public schools did not integrate until 1970—ten years after the novel was published. Mary Tucker, a teacher, said she was one of the few black residents who read the novel in 1960. White people in town, she recalled, “resented Atticus’s defending a black man.”

Another response was a bit of a shrug: The setting was so familiar. It was not until Gregory Peck came calling, said Jane Ellen Clark, director of the Monroe County Heritage Museum, that the town sat up and took notice. “Everybody has a story of Gregory Peck being here in this town, staying at the hotel, eating in the restaurants, and visiting Mister Lee. That’s when people noticed the book. If Hollywood’s gonna make a movie out of this book, then there’s something about it that’s special.”

“The Lay of the Land That Formed You”

Today in Monroeville a piece of the stone wall that once separated the houses of the Lees and Capote’s relatives is all that’s left of the old neighborhood. In the fifties, the Lee family house on South Alabama Avenue was torn down and replaced by Mel’s Dairy Dream, a white shack where hot dogs and ice cream are served through a window. The spot where Capote’s family once lived is now an empty lot, save for two of his aunt’s camellia bushes and the remnants of a stone fi shpond. There’s a plaque. The streets are wider and paved, and businesses have sprawled out far beyond the town square.

Every year at the museum, the local Mockingbird Players perform a stage version of the story to raise funds for the building’s maintenance. The second act takes place inside the old courtroom, and twelve ticket holders are seated as the jury. There’s a gift shop with books, postcards, coffee mugs, and souvenirs such as necklaces with miniaturized movie stills of Badham, the actress who played Scout. Mockingbird pilgrims come and go and stop for coffee at the Bee Hive or Radley’s Grille, the best restaurant and the only place to get a drink in an otherwise dry county.

Making those trips to Monroeville and trying to graft Harper Lee’s life onto the novel is something readers love to do, but novelists such as Childress, who has set half of his books in Alabama, have less interest in the exercise. “Her life was probably something like the life in there,” he said, “but it wasn’t so beautifully dramatically shaped, and there wasn’t one moment that pulled it all together. That’s the beauty of fiction, that’s what fiction can do: give shape to narrative.”

Wally Lamb “came to a realization over the years that I bet is true of Harper Lee, as well. You start with who and what you know. You take a survey of the lay of that land that formed you and shaped you, and then you begin to lie about it. You tell one lie that turns into a different lie, and after a while those models sort of lift off and become their own people rather than the people you originally thought of. And when you weave an entire network of lies, what you’re really doing, if you’re aiming to write literary fi ction, is, by telling lies, you’re trying to arrive at a deeper truth.”

James McBride said the deeper truth is all that matters. “To Kill a Mockingbird is rooted in reality, and it worked,” he said. “When the writer gets to the mainland, nobody asks how they got there. . . . Who cares if you got there on the Titanic, or you paddled with a boat, or you jumped from lily pad to lily pad? You got to the mainland, and that’s what counts.”

“I Didn’t Expect the Book to Sell in the First Place”

“What was your reaction to the novel’s enormous success?” radio interviewer Roy Newquist asked Harper Lee in March 1964.

“Well, I can’t say it was one of surprise. It was one of sheer numbness. It was like being hit over the head and knocked out cold. You see, I never expected any sort of success with Mockingbird. I didn’t expect the book to sell in the fi rst place. I was hoping for a quick and merciful death at the hands of reviewers, but at the same time I sort of hoped that maybe someone would like it enough to give me encouragement. Public encouragement. I hoped for a little, as I said, but I got rather a whole lot, and in some ways this was just about as frightening as the quick merciful death I’d expected.”

And that was last time Harper Lee sat for a full interview. “She did not think that a writer needed to be recognized in person and it bothered her when she got too familiar,” Miss Alice explained. “As time went on she said that reporters began to take too many liberties with what she said. So, she just wanted out. And she started that and did not break her rule. She felt like she’d given enough.”

But in 1966, the Delta Review, a New Orleans magazine, published “An Afternoon with Harper Lee,” by Don Lee Keith, a curious first-person account of meeting the novelist in Monroeville. Long on description, short on quotes, it said that Lee had stopped granting personal interviews. Lee’s quotations bear a striking resemblance to those in McCalls and Life, published in 1961. A former feature writer for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, Don Lee Keith taught journalism at the University of New Orleans until he died in 2003. His papers reside there. And while the collection has boxes filled with research, interviews, and notes on Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams, among others, there’s no documentation of what went into his article about Harper Lee.

In a remembrance, former student Perry Kasprazk wrote that Keith talked about how he got that story. “Keith was fond of saying that a telephone book was a reporter’s best friend. He qualified this maxim with the story of how he got one of the only eight interviews with Nelle Harper Lee. Keith called the residence of her sister, whose number he found in the telephone directory, and Harper Lee herself answered. Keith said, ‘Hi, my name is Don Lee Keith, and you don’t know me, but you ought to.’ Charmed, she invited him over for tea and an interview.”

We don’t know whether Harper Lee considered that an interview or not, or what she thought about anything, really, after that. We do know her novel kept growing in stature and popularity—and shows no signs of slowing down.

“To Kill a Mockingbird tells a tale that we know is still true,” Scott Turow said. “We may live, eventually, in a world where that kind of race prejudice is unimaginable. And people may read this story in three hundred years and say, ‘So what was the big deal?’ But the fact of the matter is, in today’s America, it still speaks a fundamental truth.”

“One of the unacknowledged powers of the novel,” Gurganus said, “is that, here in this little town, in these two hundred pages, a life is saved, something is salvaged, perfect justice is achieved, however improbably. And I think that that’s one of the reasons we read, is to have our faith in the process renewed.”

After To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee published four essays but not another novel, a fact that prompts speculation, lots of it. Other writers are especially good at that.

Scott Turow said, “It’s a frightening thing to another novelist to write a book that good and then shut up.”

Richard Russo said, “Whenever a writer is gifted enough and fortunate enough to write a book as good as that, you can’t help but think, What else? ”

David Kipen said, “I wish I could be one of these people who say, ‘It’s churlish to want more from a woman who’s already given us so much,’ but I’m a greedy reader, and I think a true reader has to be a greedy reader. I wanted the next book, and I will always feel cheated for not having gotten it.”

Lee Smith said, “It’s just astonishing to me that Harper Lee just stopped. I bet she hasn’t. I bet she’s sneaking around doing it. I bet she’s sitting in her house like Boo Radley, writing. I hope so.”

Oprah Winfrey said Harper Lee brought up Boo Radley when they had lunch. “She said to me, ‘You know the character Boo Radley?’ And then she said, ‘Well, if you know Boo, then you understand why I wouldn’t be doing an interview, because I am really Boo.’ ”

Boo she may be, and dragging her “shy ways into the limelight” would be a sin, to quote Sheriff Tate from the novel. And so, there is no second book.

“She didn’t put herself under the burden of writing like she did when she was doing Mockingbird. But she continued to write something. I think she was just working on maybe short things with an idea of incorporating them into something. She didn’t talk too much about it.” That’s what Miss Alice said, and then quoted her sister. “She says you couldn’t top what she had done. She told one of our cousins who asked her, ‘I haven’t anywhere to go, but down.’ ”

“Maybe for Harper Lee there was nothing else to play,” James McBride said. “She sang the song, she played the solo, and she walked off the stage. And we’re all the better for it. We’re very grateful to her for the amount of love that she’s given us.”

“A love story, pure and simple” is how Harper Lee once described her first and only book. To Kill a Mockingbird is her love, her story, her labor. She holds its birthright. And we, readers all, gave it life.

Long may it live.