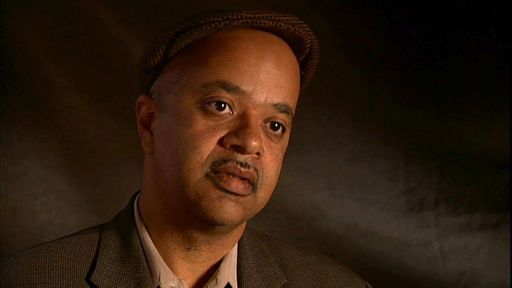

Wally Lamb, author of the critically acclaimed She’s Come Undone and I Know This Much Is True and former Director of Creative Writing at University of Connecticut, discusses Scout’s universally sympathetic voice and the ways in which To Kill a Mockingbird and all literature can act as an agent of change. Harper Lee: Hey Boo airs Monday April 2nd at 10 p.m. (check local listings).

Wally Lamb: I think for a lot of kids it’s the voice of Scout, it’s certainly not the adult voice of Jean Louise Finch, it’s Scout’s voice. I think the fact that she is a tomboy helps the boys. And I think a lot of the guys, as I recall, liked Jem too. You know, he sort of spoke their kind of language, and a lot of them had annoying little sisters, so that sort of invited them along for the ride as well.

Also, this was, this was in the seventies when I started teaching. And, you know, there was a lot of racial turmoil in the country. And I think that book, because the characters are, become sort of personally applicable, I think a story can go a lot farther lots of times than a headline can or, something on the 6:30 news. So the kids, I think it became a sort of a vehicle by which they could begin to think and sort of process some of these emotional reactions that they were having.

I know one of the things that happened at our high school during that early era when I was teaching was that, the African American kids were demanding a black history course. And the school was not providing one, and so the kids staged a demonstration out of the green near the school. And you know, I was thinking about this just today, that I think in it’s own way, To Kill a Mockingbird, sort of, and I don’t mean to overstate this, but I think To Kill a Mockingbird sort of triggers the beginning of change and certainly puts onto the stage the questions of racial equality and bigotry in a way that I think, a century earlier, Harriet Beecher Stower’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin sort of stirred things up and got people riled up enough and motivated to maybe, to maybe change things.

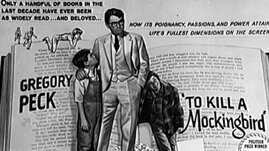

And then this, of course, the inevitable exploitation of a book that a means so much to so many people. I know a little bit about Harriet Beecher Stowe because she lived close by, in Hartford. And I know that she was sort of appalled by some of these really cheesy stage productions that started traveling the country. And I saw at one point, maybe 3 or 4 years ago up in Montpellier, VT, a staged version of To Kill a Mockingbird. And it was, it was okay, it was, I wouldn’t say it was cheesy. But it wasn’t experience, it couldn’t even approach that same kind of experience that reading the book is.