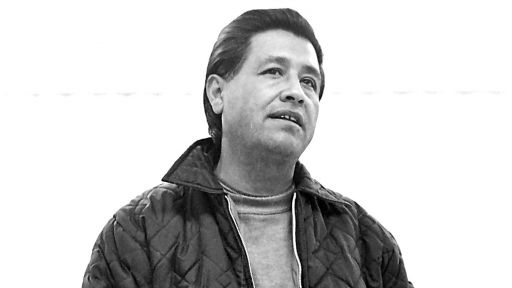

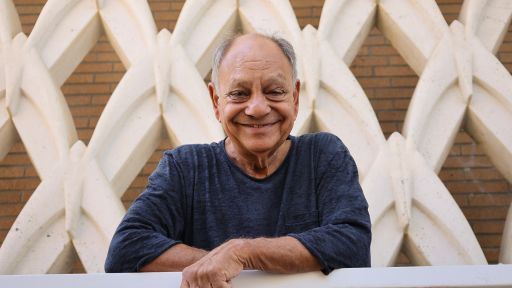

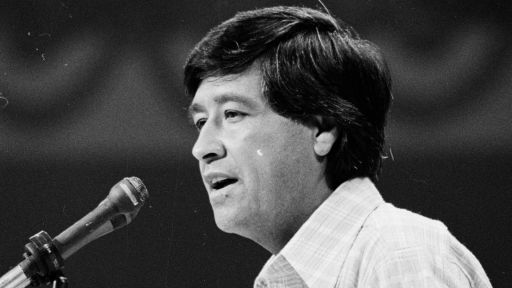

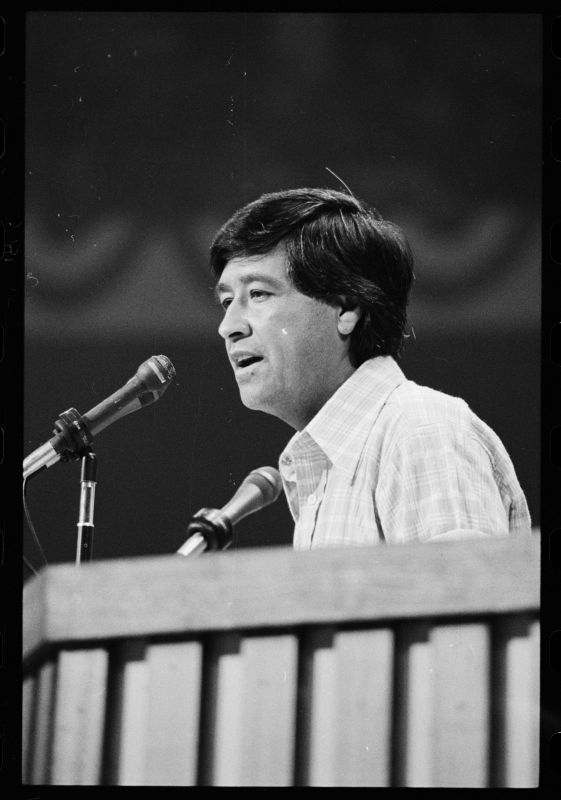

There is no question that Cesar Chavez is the most recognizable historical figure in the history of Latinos in the United States.

Democratic Convention in New York City, July 14, 1976. Cesar Chavez at podium, nominating Gov. Brown. Library of Congress.

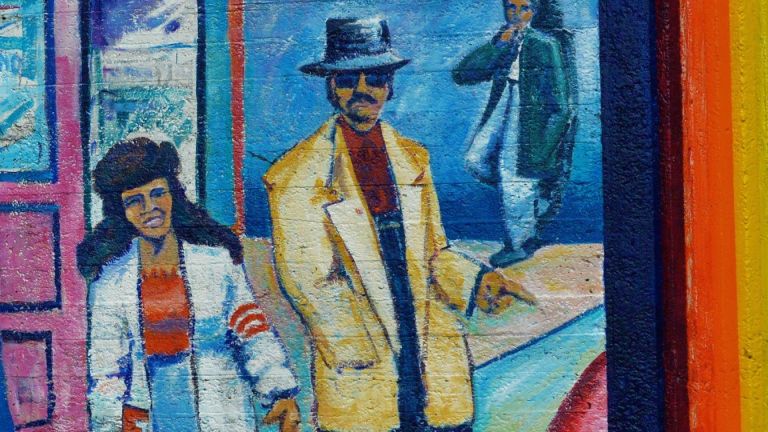

There is good reason for this. Chavez occupies a major place in U.S. history. As the leader of the farmworkers’ struggle for unionization and dignity beginning in the 1960s, Chavez accomplished what had never been done. He successfully organized farmworkers—mostly Mexicans and Filipinos—and achieved historic labor contracts with the big growers of California’s San Joaquin Valley. At the same time, Chavez inspired and encouraged the Chicano Movement’s civil rights struggles throughout the Southwest and Midwest.

In many ways, Chavez was the godfather of the Chicano Movement, the largest and most widespread civil rights movement by Mexican Americans in U.S. history.

While many have written about Cesar Chavez’s leadership qualities and abilities, unfortunately, these writers and historians have missed a crucial element of this leadership. They have ignored the deep religiosity and spirituality of Chavez. He was a brilliant organizer, but he was heavily motivated in expressing his leadership because of his faith—his Catholic faith. Chavez’s spiritual nature began with the influence of his grandmother and mother who taught him and his siblings never to hurt anyone, especially physically. This is what some refer to as abuelita theology or the theology of grandmothers. You do not harm another human being because they are God’s children. Cesar Chavez would expand what he learned from his matriarchs to include various other aspects of his faith and spirituality. This includes the following:

Chavez believed in the power of his Catholic faith.

His Catholicism inspired him to do good for others. He said: “I think there are three elements to my faith. It’s God, myself, and my brother. I’m traditional. I’m Catholic traditional. I go to Church regularly and faithfully . . . But besides that, I also have what I consider as a renewal religion. I go out and do things. That’s what I think is a real faith, and that’s what I think Christ really taught us: to go do something. We can look at His sermon [Sermon on the Mount] and it’s very plain what He wants us to do: clothe the naked, feed the hungry and give water to the thirsty. It’s very simple stuff and that’s what we’ve got to do.”

His Catholicism inspired him to do good for others. He said: “I think there are three elements to my faith. It’s God, myself, and my brother. I’m traditional. I’m Catholic traditional. I go to Church regularly and faithfully . . . But besides that, I also have what I consider as a renewal religion. I go out and do things. That’s what I think is a real faith, and that’s what I think Christ really taught us: to go do something. We can look at His sermon [Sermon on the Mount] and it’s very plain what He wants us to do: clothe the naked, feed the hungry and give water to the thirsty. It’s very simple stuff and that’s what we’ve got to do.”

Chavez fought for the human dignity of farmworkers and others who faced inhuman treatment.

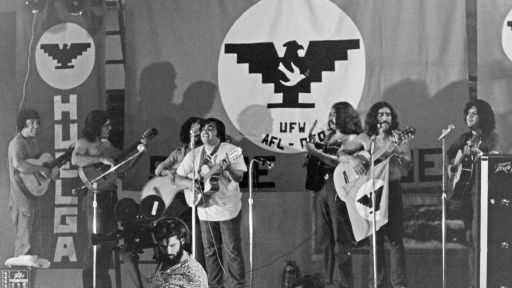

Of this he stated: “We must never forget that the human element is the most important thing we have—if we get away from this, we are certain to fail.” Human dignity was especially important for the poor who received no such treatment. Of the poor, Chavez added: “It is more than a union (UFW) as we know it today that we have to build. It is movement of the poor . . . We know that our cause is just, that history is a story of social revolution and that the poor should inherit the land.”

Self-sacrifice was very much a part of Chavez’s leadership.

He more than others had to sacrifice for others. “When we are really honest with ourselves, we must admit that our lives are all that really belong to us,” he confessed. “So it is how we use our lives that determines what kind of men we are. It is my deepest belief that only by giving our lives do we find life. I am convinced that the truest act of courage, the strongest act of manliness is to sacrifice ourselves for others in a totally nonviolent struggle for justice.”

Of course, nonviolence was part of Chavez’s faith that he is best known for.

Chavez recognized that nonviolence was not easy, especially for men. He tellingly remarked: “I am not a non-violent man. I am a violent man who is trying to be nonviolent.” Chavez often spoke of nonviolence. Yet for him, nonviolence was more than a tactic; it was a way of life. But nonviolence did not mean turning the other cheek or being passive. Chavez believed in what he called “militant nonviolence.” Nonviolence called for being active and struggling for your rights and dignity. It meant going on strike (huelga) and picketing. “Nonviolence is more powerful than violence,” Chavez pronounced. “We are convinced that nonviolence supports you if you have a just and moral cause. Nonviolence gives the opportunity to stay on the offensive, which is of vital importance to win any contest.”

Cesar Chavez struggled for social justice for farmworkers and for other disenfranchised people, but it was a social justice imbued by his faith.

He declared: “If I’m going to save my soul, it’s going to be through the struggle for social justice.” And he added: “We seek our basic God-given rights as human beings. Because we have suffered and are not afraid to suffer—in order to survive we are ready to give up everything, even our lives, in our fight for social justice.”

There is little question that Cesar Chavez’s leadership was influenced by his faith and spirituality. We need to begin here in order to understand the man and his cause. Chavez said it all when asked after many years of struggling for the rights and dignity of farm workers what motivated him to continue the good fight. Chavez tellingly responded:

“Today I don’t think that I could base my will to struggle on cold economics or on some political doctrine. I don’t think there would be enough to sustain me. For me the base must be faith.”