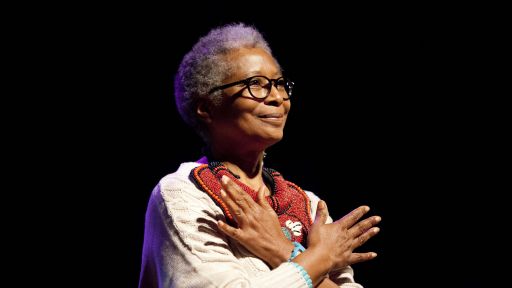

In the 21st century, so many decades removed from the struggle for labor justice that began with the United Farm Workers Union (UFW) in California, the struggle continues.

When I read about the exploitation of Latine immigrant children as workers in the Midwest and in the South, the raging controversy over immigration and the healthcare and drug problems in Chicano communities, I despair. So much is still to be done! But I find hope in the fact that at one time, others rose in response to the outrage and the horrendous working conditions of farmworkers.

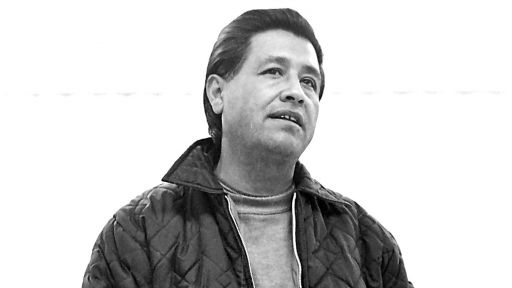

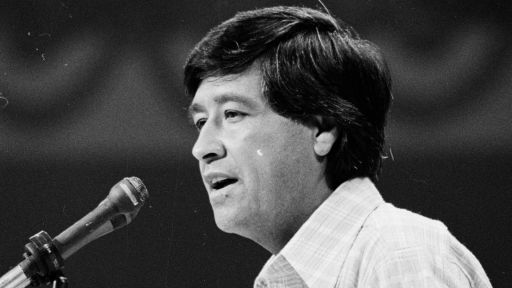

I first became aware of Cesar Chavez, the enigmatic and at times controversial figure in Chicane history, when I was in my first year at Laredo Junior College in the 1965.

I was an office clerk at a utilities company and attending night classes. Many of my friends were off fighting in Vietnam; my brother was killed there in 1968 and the tumultuous times included many issues of social justice. I, as the oldest of a family of 11, felt moved to action, but I felt there was little I could do. But the grape boycott was in full swing, and I happily joined and promoted that seemingly minor activity in solidarity with the Union.

The ones who brought news of the strike and of the farmworkers movement in California were a few labor activists in my community of Laredo, Texas, far removed geographically from the Delano Grape Strike but fully supportive of their efforts. Although my family had worked in the fields picking cotton, we had not joined the thousands who migrated “al norte” every year to pick crops. Yet I had many friends and family who as migrant workers had experienced many of the hardships Chavez and the Union were working to address.

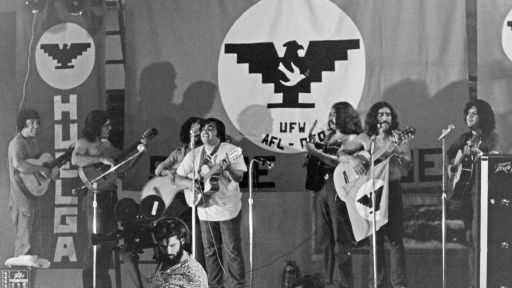

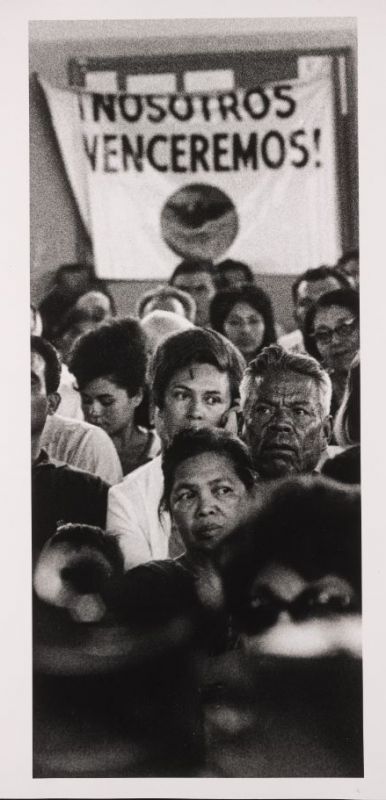

UFW protestors, Jon Lewis photographs, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library © Yale University. All rights reserved

I knew about labor strikes as my father, who worked for the local smelter, was a labor leader and often, we suffered as a family the decision of the Texas mining and smelting workers’ strikes. Serendipitously, as a student, I was also engaged in research on labor movements in my community and discovered that women like Emma Tenayuca and Jovita Idar were instrumental in local movements for fair labor laws. So I was well aware of the power of labor strikes, and it seemed natural to join the boycott.

In addition to supporting the UFW strikers and boycotting grapes, I joined La Raza Unida, a political party that offered to combat what I saw as the corruption and nepotism of the “Old Party” or “Partido Viejo” that held a stranglehold in my community. What I mean by joined, however, is not the radical engaged activism that I yearned for. After all, I had a job and my family depended on me financially; I couldn’t just drop it all and join the political activists. But I attended rallies and talks they offered. In my mind, Chavez and the Union were on the right side of things, the side I wanted to be on.

I remember many a Saturday afternoon in the early 70s at various plazas in Laredo, listening to speakers like Antonio Orendain, who worked alongside Chavez and started the Texas Farmworkers Union, and José Angel Gutiérrez. And later as a graduate student in Kingsville, Texas marching with activists in Corpus Christi, my commitment deepened and I can say their work marked my commitment to work for la raza, the people, in any way possible.

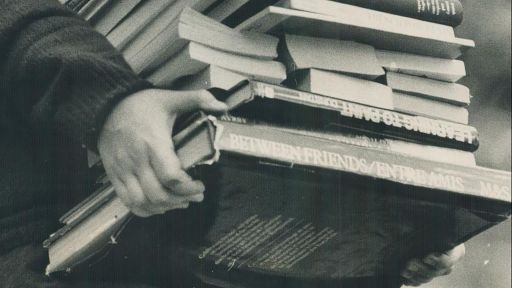

I began teaching as a graduate student, 50 years ago at what was then Texas A&I University—now it is Texas A&M, Kingsville. Many of my students were first generation sons and daughters of those who were working in the fields; indeed, many of them still migrated north to work in the fields. It was not a long stretch then, to include the literature I could find about our conditions. The publication of Tomas Rivera’s “y no se lo tragó la tierra” and “Bless Me Ultima” by Rudy Anaya and the many novels by Rolando Hinojosa Smith set in rural South Texas opened up a world of literary study that had been denied me. These works, along with the early anthology of our literature by Tomas Ybarra Frausto and Antonia Castañeda, “Literatura Chicana: Texto y Contexto/Chicano Literature: Text and Context” (1972), became mainstays in my classes at the University of Nebraska when I was working on my doctorate. Later, the work of Gloria Anzaldúa opened up new venues for investigation of that landscape and culture that is south Texas.

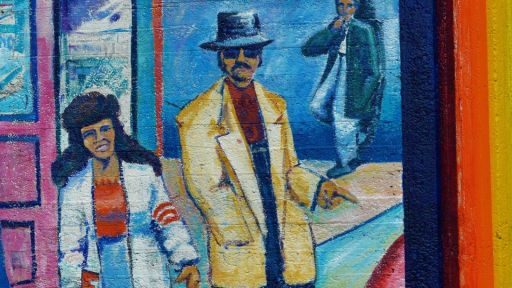

But it began with Cesar and with Dolores Huerta and with the numerous artivists who followed them and supported them like Luis Valdez’s “Teatro Campesino” and “Teatro Esperanza.” In Texas and locally, I was joined by many like-minded activists like Rebecca Flores and Martha Cotera, who foregrounded the work of women in our history and in our struggles for justice.

But it began with Cesar and with Dolores Huerta and with the numerous artivists who followed them and supported them like Luis Valdez’s “Teatro Campesino” and “Teatro Esperanza.” In Texas and locally, I was joined by many like-minded activists like Rebecca Flores and Martha Cotera, who foregrounded the work of women in our history and in our struggles for justice.

My work as an academic and a writer has certainly been influenced by the work of the UFW and its leaders. And I continue to teach the history of our struggle—a struggle that may have taken on new challenges, but is not quite over yet. Today, many decades removed from that young idealist of the 1960s, I still find comfort in the work that the UFW and so many workers for justice achieved. In my novel, “Canícula,” there’s a piece titled “Politicos” that I believe is a direct result of my political awareness. In “Champú, or Hair Matters”—a novel I am working on and that is set in Laredo in the early 2000s—I include the characters whose lives were linked to the movement, that same Chicano Movement that shaped me as a scholar and as a teacher. My teaching, my scholarship on literary and cultural expressions, and my activist work today are all linked to those formative years of my 20s and 30s when the Chicano Movement was part of my life. Undoubtedly, without the Chicano Movement, I would not be who I am.