If you want to understand the contours of post-war American political discourse, there are few starting places better than “Firing Line,” the longest-running political talk show of the 20th century.

Before the media’s love-hate relationship with former President Donald Trump, it was William F. Buckley, the show’s creator and host, who made for captivating political television.

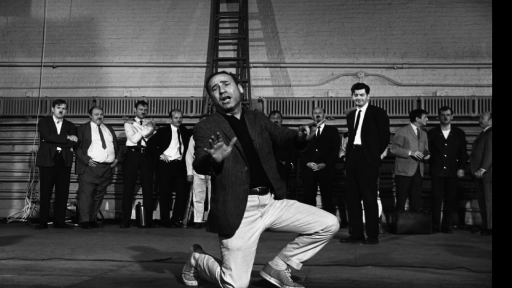

Buckley was a conservative hardliner, a sharp wit, and an intellectual pugilist whose distinctive mannerisms, multi-syllabic vocabulary and bon mots frequently won over audiences. On his show, he debated the likes of Noam Chomsky, Huey P. Newton, and Saul Alinsky about the political issues of the day, such as the Vietnam War and the underpinnings of poverty. But it was his May 1968 episode with Allen Ginsberg that so perfectly captured the aesthetics of America’s political divide, which echo into today.

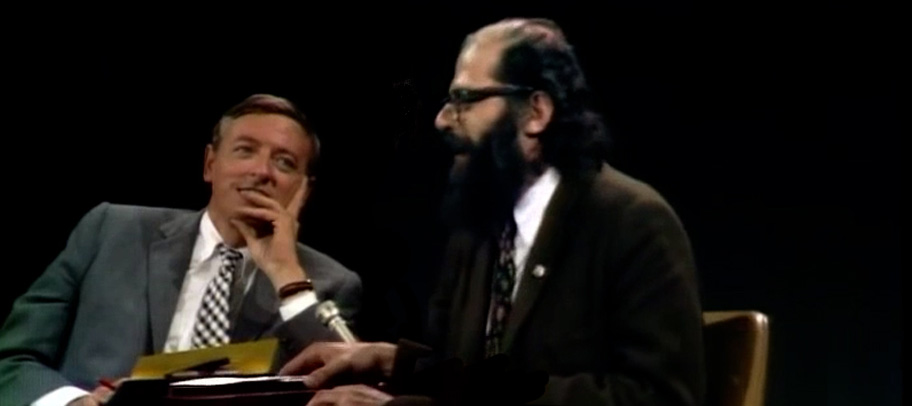

In that episode, Ginsberg wore a slightly oversized brown sport coat with blue jeans, dusty black work boots and a whimsically decorated tie that telegraphed that he was ignorant of, or perhaps disinterested in, Good Taste (a notion that sociologist Pierre Bourdieu accurately described as the preferences of the ruling classes). Ginsberg had a bushy, unkempt beard, which looked like the straggly cotton threads hanging from his jeans’ broken hem. By contrast, Buckley was neat and well-groomed, with his hair parted to the side. The conservative columnist wore a grey single-breasted suit with a white button-down collar shirt, polished black calfskin shoes and a tastefully patterned Shepherd’s check necktie.

During the one-hour conversation, Ginsberg asked if he could sing a song praising Krishna, to which Buckley acceded. But when the Beat Generation poet started chanting “Hare Krishna” while playing his harmonium, Buckley leaned far back in his chair. With a finger on his chin and his eyes widening, he flashed a strained smile. “That was the most unharried Krishna I’ve ever heard,” he said at the end of Ginsberg’s performance. Buckley’s ability to gently mock liberals and leftists under a veneer of civility was, in part, what made him such good television material and a hero among conservatives.

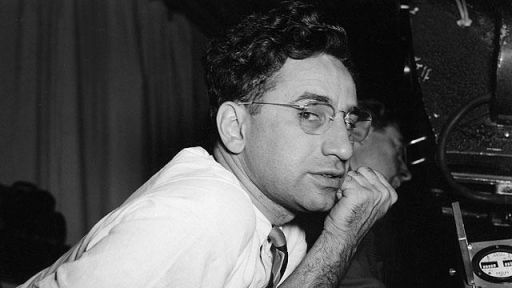

Political commentators are rarely shining examples of style, but Buckley is an icon in a tradition known as the Ivy League Look.

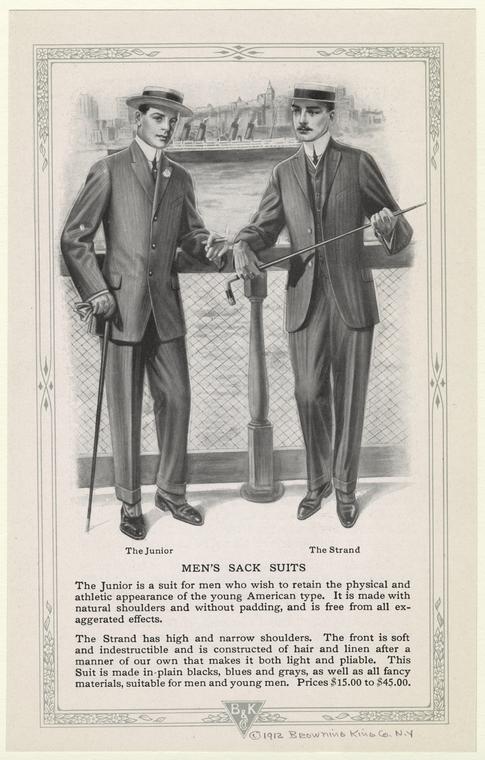

Men’s sack suits, 1912. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, NYPL.

The story of this style really begins at the turn of the century, 25 years before his birth, when Brooks Brothers debuted their No. 1 Sack Suit. This soft-shouldered, hook vent, dartless form of tailoring carried American men from the hopping jazz clubs of the Roaring Twenties through the Great Depression and onto college campuses in a booming post-war America. For a time, what landed at Brooks Brothers’ Madison Avenue flagship became the building blocks of classic American dress.

Brooks Brothers introduced American men to Harris Tweed sport coats, English foulard ties, Shetland knits, bleeding madras and washable seersucker suits. Many of their styles came from elite European sports, such as the button-down collar that company founder Henry Brooks saw on British polo players and then imported into the US by placing the design on his oxford shirts (first in a pullover style, then a coat-front variety). That’s presumably also where the company got the idea to bring in their princely polo coats, a double-breasted overcoat style that descended from the wrap coats polo players wore between periods of play.

For much of the 20th century, Brooks Brothers dressed American elites, mostly members of those social classes that saw their fortunes rise with industrial capitalism—Boston Brahmins, Old Money WASPs, and members of the professional-managerial class in coastal urban centers. This connection gave this look its patrician meaning, making it an elite signifier that inspired countless copycats. For a time, the Ivy League Look was a sterling symbol of all that is good: casualness, youth, education, trustworthiness, dependability, sport and professionalism.

Born into a wealthy family, Buckley grew up in the social milieu that gave this style status.

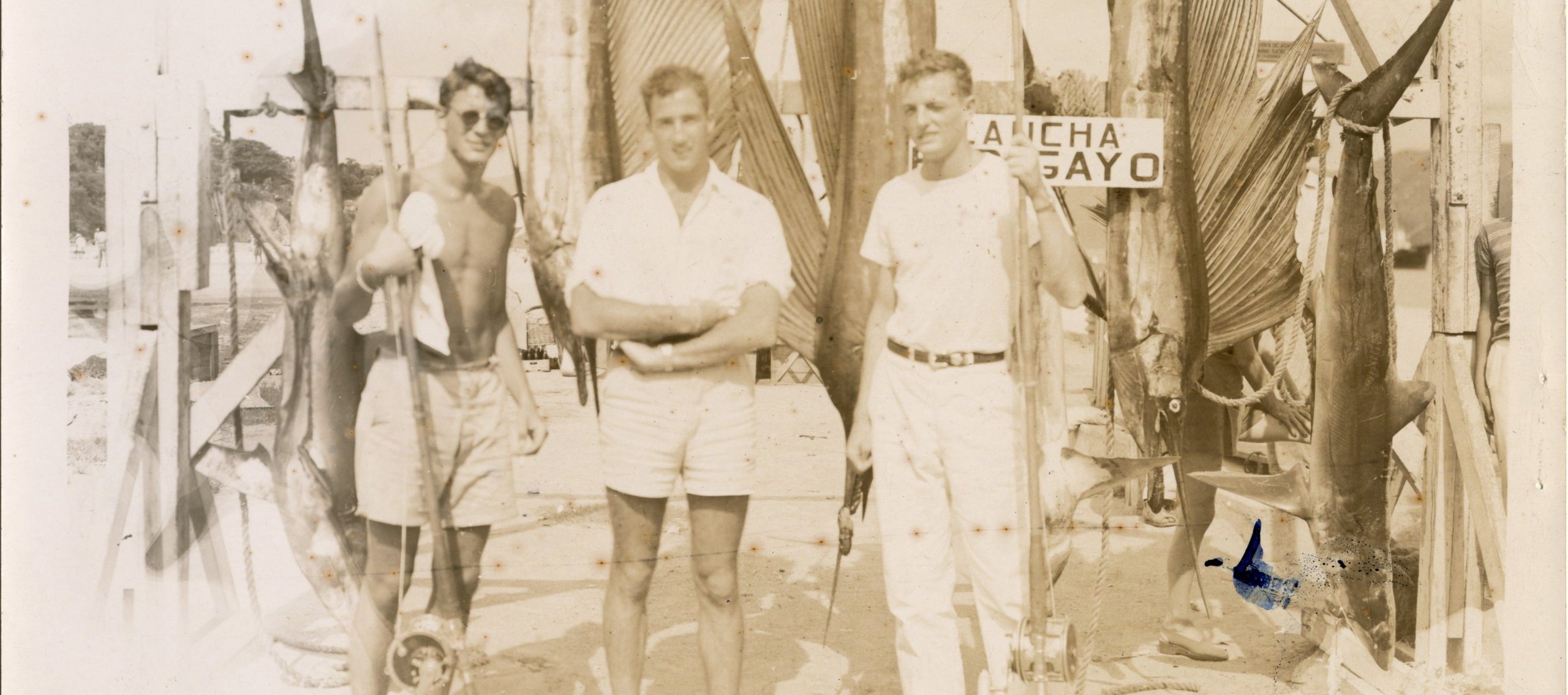

His father was a Texan lawyer and oil developer who made his fortune in Latin America; his mother was a member of the Southern gentry. Buckley moved around a bit but grew up for a time on the family’s sprawling estate in Sharon, Connecticut—where he would later organize college students to form the Young Americans for Freedom in 1960 and would be buried there when he died in 2008. By his own admission, this is where he was happiest, between the ages of five and seven. The young Buckley then studied in Paris, London and the Jesuit preparatory school St. John’s Beaumont in the English village of Old Windsor. As a youth, he picked up multiple languages (French and Spanish), learned how to play the harpsichord and developed a love for elite sports (horses, hunting, sailing and skiing). Photos of him as a young boy show him wearing perfectly tailored tweeds with lapels that looked like they were blooming out of his jacket’s buttoning point. The roll on those lapels can only be achieved through skilled hand tailoring.

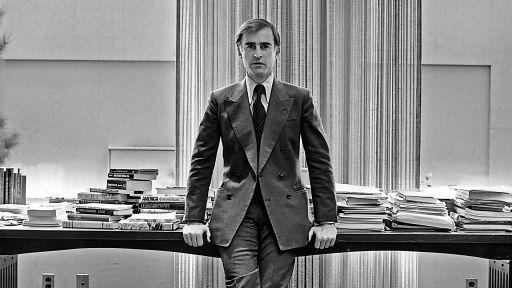

Buckley’s alma mater, where he crystallized into a conservative critic and bedeviled his professors, was an epicenter for the Ivy League Look. Located just off Yale’s campus was J. Press, one of the satellite clothiers that orbited Brooks Brothers in the Ivy League Look universe. It was here where Yale students could purchase brass button blazers (with the lapel rolling down to the second button), brushed Shetland knits (charmingly known as Shaggy Dogs), striped schoolboy scarves, flat-front trousers with turn-up cuffs, and oxford-cloth button-downs with a flapped chest pocket (distinctive to J. Press). One can safely assume he shopped here since a 1954 photo shows him in these clothes.

Buckley at the News building, the 1950 Class Book – Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

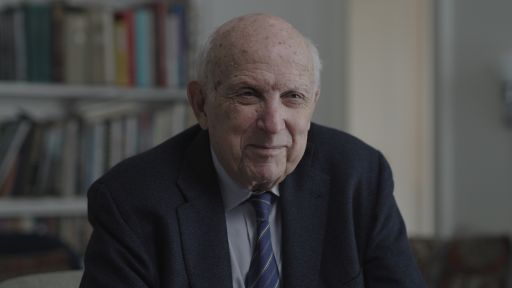

As a dresser, Buckley lacked the refinement of some of his fellow blue bloods, such as President John F. Kennedy and A.J. Drexel Biddle Jr., whom Esquire writer George Frazier identified as the most stylish man alive in his 1960 essay, “The Art of Wearing Clothes.” However, Buckley possessed a vital quality—authenticity. Even in his most disheveled state—such as the time in 1975 when Richard Avadon photographed him in a crinkly linen suit that could have been tailored better—he carried a sense of confidence in these clothes that can only come from decades of familiarity. Three-button tweeds with two-button cuffs, worn with button-down collars and regimental striped ties, were as natural to him as his languid drawl.

The connection between these clothes and the American patrician class is what gave this style its enduring meaning, which in turn has propelled Ralph Lauren into a multi-billion dollar business. At the same time, the Ivy League Look struggled during the immediate post-war years because it became too closely tied to The Establishment. Against the backdrop of the Civil Rights movement and anti-Vietnam War protests, along with Marlon Brando and James Dean striking a rebel pose with their working-class gear, many young people expressed new identities through different clothes. Establishment types wore the suit; anti-establishment types took to white tees, leather jackets, and jeans.

It didn’t help that one of the era’s most prominent conservative voices, Buckley, argued in favor of continuing segregation in the American South. “[T]he White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race,” he wrote in a 1957 National Review column. Buckley continued this argument when he debated James Baldwin at Cambridge Union in 1965. Both men wore coats and ties that day, but just as Buckley’s background granted him some authenticity in the Ivy League Look, he was also more narrowly defined by this style.

It didn’t help that one of the era’s most prominent conservative voices, Buckley, argued in favor of continuing segregation in the American South. “[T]he White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race,” he wrote in a 1957 National Review column. Buckley continued this argument when he debated James Baldwin at Cambridge Union in 1965. Both men wore coats and ties that day, but just as Buckley’s background granted him some authenticity in the Ivy League Look, he was also more narrowly defined by this style.

Shortly after Buckley died in 2008, images of him started circulating on menswear blogs.

There are photos, each shared thousands of times, of Buckley sporting a suit while riding a scooter down Park Avenue, donning a tan crewneck while sailing, and wearing a sport coat with a regimental striped tie while taking a phone call inside a limousine (a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel dog faithfully sitting by his side). These images proved potent for the same reason the style ascended in the first half of the 20th century: the tailoring is well done, the styles are a little more casual than their European counterparts, and the clothes hint at a kind of privilege bestowed only through inherited wealth. The conflicts that Americans had in the 1960s still influence politics today.

However, many people have forgotten the specifics—such as Buckley’s views on segregation—allowing the writer to exist, at least in some digital spaces, as a kindly Ralph Lauren mannequin.