Emergent technologies inevitably pose ethical and legal dilemmas. Artificial Intelligence has surfaced as a particularly challenging subject, especially in its relationship to the First Amendment. One of the most prominent companies at the center of this debate is Clearview AI, which collects and sells facial recognition data. Clearview AI has been legally represented by First Amendment attorney Floyd Abrams, who holds that the company’s facial recognition data is protected as free speech.

To build its database, Clearview AI has collected over 30 billion images from the internet and social media. Its app can potentially identify anyone through access to just one public facial image. This technology has raised serious privacy and surveillance concerns within a complicated first amendment debate. At the forefront of this conversation has been tech reporter Kashmir Hill, whose New York Times’ article first brought major attention to the issue in 2020. Hill, interviewed in Floyd Abrams: Speaking Freely, has since continued to investigate the origin and influence of Clearview AI.

Her latest book, “Your Face Belongs to Us” uncovers the startup’s rise, power and implications. In this first chapter, Hill details Hoan Ton-That’s early path to co-founding the controversial company.

Chapter 1 – A Strange Kind of Love

In the summer of 2016, in an arena in downtown Cleveland, Ohio, Donald Trump, a real estate mogul who had become famous hosting a reality TV show called The Apprentice, was being anointed as the Republican Party’s presidential candidate. Trump had no government experience, no filter, and no tolerance for political correctness, but his famous name, right-wing populist views, and uncanny ability to exploit his opponents’ weaknesses made him a powerful candidate. It was going to be the strangest political convention in American history, and Hoan Ton-That did not want to miss it.

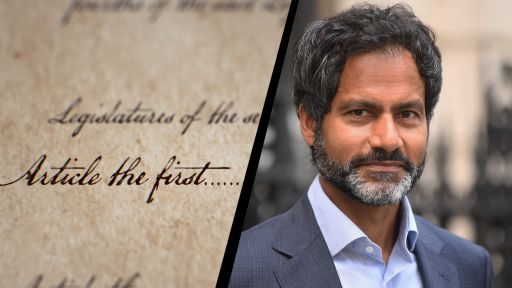

Hoan Ton-That, computer engineer and co-founder of Clearview AI. Image from Floyd Abrams: Speaking Freely by SALTY Features.

Ton-That, twenty-eight, did not look, at first glance, like a Trump supporter. Half Vietnamese and half Australian, he was tall—six feet, one inch—with long, silky black hair and androgynous good looks. He dressed flamboyantly in paisley print shirts and suits in a rainbow of colors made bespoke in Vietnam, where, his father told him, his ancestors had once been royalty.

Ton-That had always followed his curiosity no matter where it had taken him. As a kid, growing up in Melbourne, Australia, he had tried to figure out electricity, plugging an extension cord into itself in the hope that the current would race around in a circle inside. Once, after seeing someone steal a woman’s purse, he walked up to the thief and asked why he’d done it. The guy pushed him over and ran away. When Ton-That’s dad brought a computer home in the early 1990s, Ton-That became obsessed with it, wanting to take it apart, put it back together, play games on it, and type commands into it. Because his growth spurt came late, Ton-That was “little Hoan” to his classmates, and bullies targeted him, particularly those who didn’t like the growing Asian demographic in Australia. Ton-That had close friends with whom he played guitar, soccer, and cricket, but he felt like an outsider at school.

When he was fourteen, he taught himself to code, relying on free teaching materials and video lectures that MIT posted online. Sometimes he would skip school, tape a “Do Not Disturb” sign on his bedroom door, and spend the day with virtual programming professors. His mother was perplexed by his love of computers, pushing him to pursue a musical career instead after he placed second in a national competition for his guitar playing. “Very often, you’d find him on the computer and the guitar at the same time,” his father, Quynh-Du Ton-That, said. “Back and forth between the keyboard and the guitar.”

When it came time for college in Canberra, Ton-That chose a computer engineering program, but he was bored out of his mind by professors teaching a mainstream programming language called Java. Ton-That was into “computer snob languages,” such as Lisp and Haskell, but those were about as likely to get him a job as studying Latin or ancient Greek. Instead of doing schoolwork, he created a dating app for fellow students called Touchfelt and spent a lot of time on a new online message forum, eventually called Hacker News, which catered to a subculture of people obsessed with technology and startups. When a California investor named Naval Ravikant put up a post there saying he was investing in social media startups, Ton-That reached out to him.

When it came time for college in Canberra, Ton-That chose a computer engineering program, but he was bored out of his mind by professors teaching a mainstream programming language called Java. Ton-That was into “computer snob languages,” such as Lisp and Haskell, but those were about as likely to get him a job as studying Latin or ancient Greek. Instead of doing schoolwork, he created a dating app for fellow students called Touchfelt and spent a lot of time on a new online message forum, eventually called Hacker News, which catered to a subculture of people obsessed with technology and startups. When a California investor named Naval Ravikant put up a post there saying he was investing in social media startups, Ton-That reached out to him.

He told Ravikant about his entrepreneurial ambitions and the lack of appetite for such endeavors in Australia. Ravikant told him he should come to San Francisco. So at just nineteen years old, Ton-That moved there, drawn halfway around the world by the siren song of Silicon Valley.

Ravikant picked up the jet-lagged Ton-That at the airport, found him a friend’s couch to sleep on, and talked his ear off about the booming Facebook economy. The social network had just opened its platform to outside developers. For the first time, anyone could build an app for Facebook’s then 20 million users, and there was a plethora of vacuous offerings. The epitome of those would be FarmVille, a game that let Facebook users harvest virtual crops and raise digital livestock. When the company behind FarmVille went public, it revealed an annual profit of $91 million on $600 million in revenue, thanks to ads and people paying real money to buy digital cows.

“It’s the craziest thing ever,” Ravikant told Ton-That. “These apps have forty thousand new users a day.”

Ton-That couch surfed for at least three months because he didn’t have the credit history needed to rent an apartment, but the San Francisco Bay area, with its eclectic collection of entrepreneurs, musicians, and artists, was otherwise a good fit for him. He loved being in the heart of the tech world, meeting either startup founders or those who worked for them. He became friends with early employees at Twitter, Square, Airbnb, and Uber. “You see a lot of this stuff coming out, and it just gives you a lot of energy,” he said.

America’s diversity was novel to him. “There wasn’t African American culture or Mexican culture in Australia,” he said. “I had never heard of a burrito before.” And he was shocked, at first, by San Francisco’s openly gay and gender-bending culture.

Eventually, though, Ton-That let his hair grow long and embraced a gender-fluid identity himself, though he still preferred he/him pronouns. Before he turned twenty-one, he got married, to a Black woman of Puerto Rican descent with whom he performed in a band. (They were in love, he said, but it was also his path to a green card.)

Desperate to make money and continue funding his stay in the United States, he jettisoned his ideals and got to work cranking out Facebook quiz apps. Rather than a “snob” computer language, he adopted what everyone else was using: a basic, utilitarian language called PHP. Speed was more important than style when it came to cashing in on the latest consumer tech addiction. After one of Ton-That’s apps got some traction, Ravikant gave him $50,000 in seed money to keep going.

More than 6 million Facebook users installed Ton-That’s banal creations—“Have You Ever,” “Would You Rather,” “Friend Quiz,” and “Romantic Gifts”—which he monetized with little banner ads. Initially, Ton-That could get a Facebook user to invite all of their friends to take the quiz with just a few clicks. But the social network was starting to feel spammy. Every time users logged in, they were bombarded with notifications about their friends’ FarmVille activities and every quiz any of their friends had taken. Facebook decided to pull back on third-party developers’ ability to send notifications to a user’s friends, putting an end to the free marketing that Ton-That and others had come to rely on and drying up their steady stream of new users.

Still, Ton-That couldn’t believe how much data Facebook had given him along the way: The people who had installed his apps had ceded their names, their photos, their interests, and their likes, and all the same information for all of their friends. When Facebook opened its platform to developers like Ton-That, it didn’t just let new third-party apps in; it let users’ data flow out, a sin outsiders fully grasped only a decade later during the Cambridge Analytica scandal. But Ton-That didn’t have a plan for all that data, at least not yet.

Soon the Facebook app craze faded, and a new tech addiction arrived in the form of mobile apps. Soon after Ton-That arrived in California, Apple released the iPhone. “It was the first thing I got in San Francisco before I even got an apartment,” he said. The iPhone almost immediately became an expensive, must-have gadget, and the App Store became a thriving marketplace, with monied iPhone users willing to hand over their credit card numbers for apps that would make the most of their precious devices. As the smartphone economy began to boom, Ton-That sold his Facebook quiz company, paid Ravikant back, and turned to making iPhone games.

It was fun at first—and lucrative. He created a Pavlovian game called Expando that involved repeatedly tapping the iPhone’s screen to blow up digital smiley face balloons, while tilting the phone this way and that to roll the balloons away from orange particles that would pop them. People paid up to $1.99 each to download it, which added up quickly when the game proved popular. But over time, the iPhone game space got more competitive and the amount Ton-That could charge dropped until eventually he had to make the game free and rely on the money he made from annoying banner ads.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, companies like Google and Facebook convinced much of the planet that the tech industry had a noble plan to connect and enrich the global population, unlock the whole of human knowledge, and make the world a better place. But on the ground in San Francisco, many developers like Ton-That were just trying to strike it rich any dumb way they could.

Excerpted from “Your Face Belongs to Us” by Kashmir Hill Copyright © 2023 by Kashmir Hill. Excerpted by permission of Random House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Photo of Kashmir Hill by Earl Wilson.