There’s a moment near the end of “Libra” that I can’t shake.

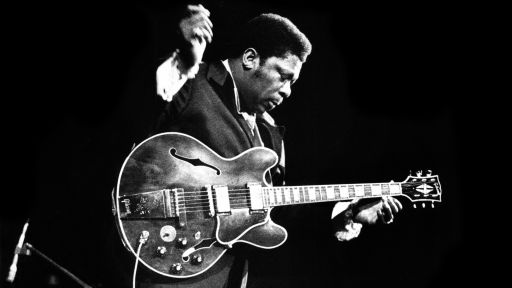

It comes around the 3:35 mark, after a short drumroll silences the band, giving its leader Max Roach the floor. Then the drums hit like machine gun bullets, a raucous ratatat that’s rightfully violent. The song was released in 1965, five years after Roach’s music turned political. A Black American in the time of civil rights struggle, his work was forceful yet comforting, equal parts rage and tranquility. Roach used the beat of his drum to convey the angst of daily existence. Black people couldn’t just be: they had to be love, fire, peace and fury. Through drum solos like these, and on albums like “It’s Time” and “Percussion Bitter Sweet,” Roach fought against such living. Be present, but be aware, his music urged.

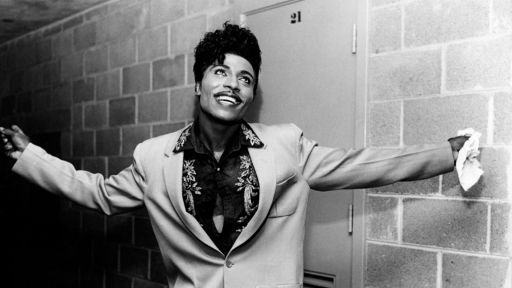

Roach cut a stately presence behind the drum kit. Adorned in a tailored suit or tuxedo, bare-faced or mustached with big glasses and a short afro, he looked regal, like a pioneer. And he was: In the 1940s, he established bebop alongside the drummer Kenny Clarke, the saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker and the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. He was the house drummer at Monroe’s Uptown House in Harlem, where he played with Bird and Dizzy using quick rhythms that prioritized the ride cymbal and bass drum.

That style hadn’t been heard before; no one else played with such speed and vigor. After playing with cornerstone musicians like Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell and Miles Davis, he formed his own quintet with the trumpeter Clifford Brown in 1954 and became one of the hottest players on the scene.  But that was cut short; Brown and the band’s pianist Richie Powell died in a car accident two years later.

But that was cut short; Brown and the band’s pianist Richie Powell died in a car accident two years later.

Something changed in Roach. He became bleak and his music more resistant. This approach crystallized in 1960, beginning with the album “We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite,” a sharp castigation of global racism and the hoodlums who perpetrate it.

Featuring the singer Abbey Lincoln, to whom Roach was married for eight years, “We Insist!” broke new terrain in Black Classical Music: Though it wasn’t the first time someone of that ilk had vocally expressed their dismay, Roach’s album didn’t flinch; songs like “Driva’Man,” “Triptych: Prayer / Protest / Peace” and “Tears for Johannesburg” examined slavery, the civil rights movement and apartheid with jarring clarity. On “Driva’ Man,” the strike of Lincoln’s tambourine simulated a whip slapping the servant’s skin. On the “Protest” section of “Triptych,” Lincoln used yelps and screams to unpack her frustration with America. A year later, on the album “Percussion Bitter Sweet,” Roach doubled down on the social commentary. Polyrhythmic drums and melodic sighs paid homage to traditional West African textures, the Black Nationalist leader Marcus Garvey, and the ongoing racial crisis in South Africa.

But it’s on the 1962 album “It’s Time” — on the title track, in particular — that Roach’s vision coalesced. The soaring vocals and propulsive drums were beautiful and seething, and sounded the alarm that the time for equality was now. I’ve always wondered how Roach could impart such emotion without uttering a word. But I think that speaks to the feeling he put into his art; the angst was so palpable that lyrics weren’t needed. “I’m just trying to describe what I see and experience in my lifetime being a person of color,” Roach said in a 2001 interview. “That’s in all my work, because it’s not easy to live in this country that we do being a person of color. When you find yourself being lynched because of color, it’s some barbaric stuff.” He didn’t back off his stance as he got older; he got more experimental, working with avant-garde musicians like Archie Shepp and Anthony Braxton, and forming the percussion ensemble M’Boom in 1970.

Roach wasn’t the only jazz musician using his platform to denounce racism. John Coltrane’s “Alabama” was a meditative blues song recorded in response to the church bombing in Birmingham that killed four young Black girls. Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” was an upbeat jab at the Jim Crow South. Before Roach’s political stance, in 1959, Charles Mingus released the song “Fables of Faubus” as a diss to Arkansas governor Orval Faubus, who in 1957 sent the National Guard to Little Rock Central High School to prevent racial integration.

Before these artists, Black jazz musicians weren’t encouraged to address topics like these. Roach made it okay to do so across the course of an album. And he didn’t always need help; the song “Conversation” — from 1958’s “Deeds, Not Words” — was an extended drum solo that expressed many moods within its four minutes. In it I hear the essence of Black charisma, the swankiness of an uptown supper club, the uncertainty of a night out.

In that way, he was an innovator. The bang of the drum was more than enough. Yet when scholars rattle off the pillars of jazz, they mention the usual names — Miles, ‘Trane, Dizzy, Duke and Ella — without mentioning Roach’s contributions to the genre. His being in the background as a drummer and not out front as a vocalist, trumpeter or saxophonist might explain the oversight, but he was right there the whole time and should be considered a building block of the genre. When you hear a politically-minded jazz album today, be it Shabaka & The Ancestors’ “Wisdom of Elders” or “Irreversible Entanglements’” self-titled debut, it hearkens back to Roach and the groundwork he laid 60 years ago. A legend then, now and always, no other jazz musician has his rewind factor. That he can make me replay a 40-second drum solo on full blast like it’s hip-hop only bolsters his genius. Now back to this section of “Libra.” I still can’t shake it and likely won’t for some time.