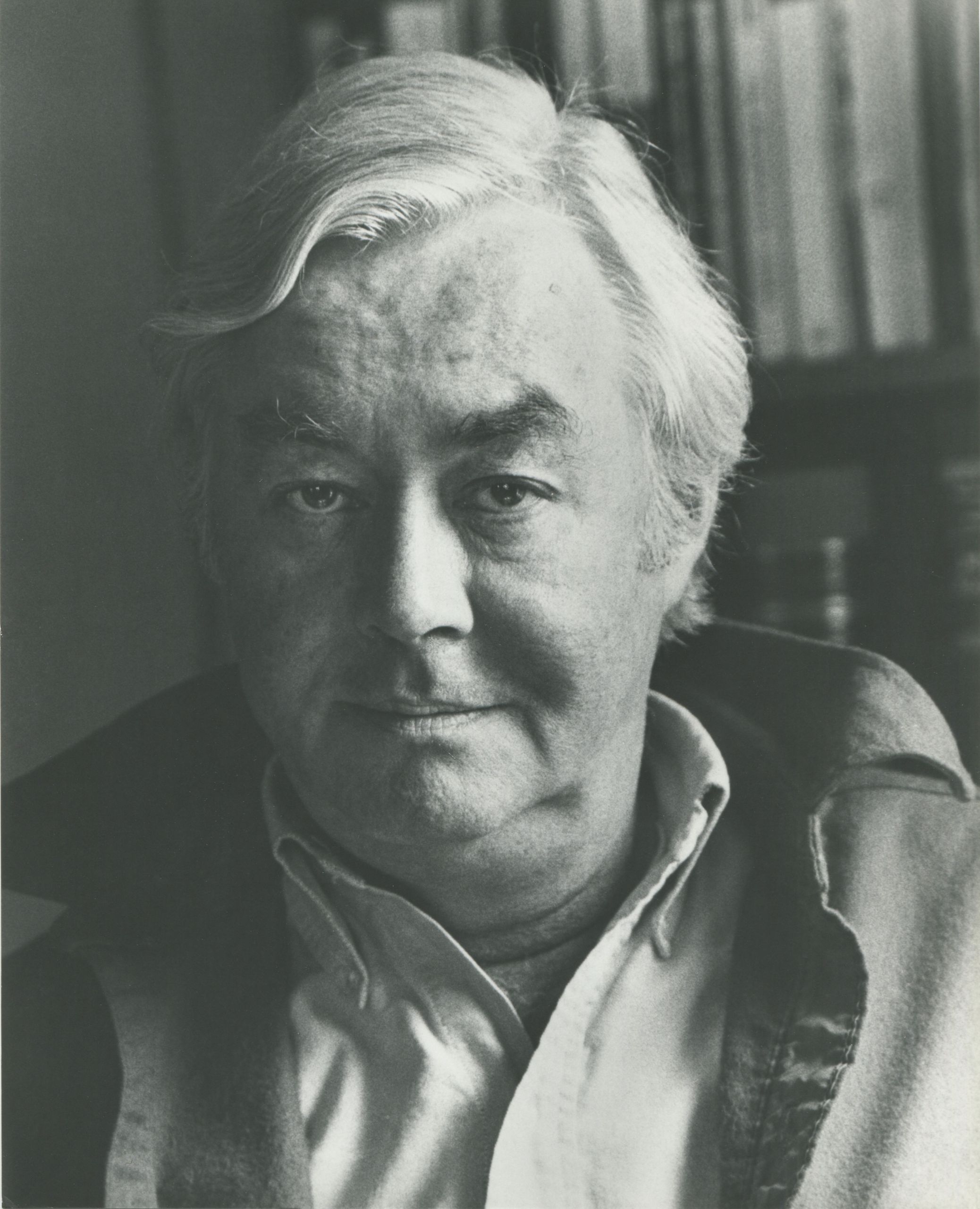

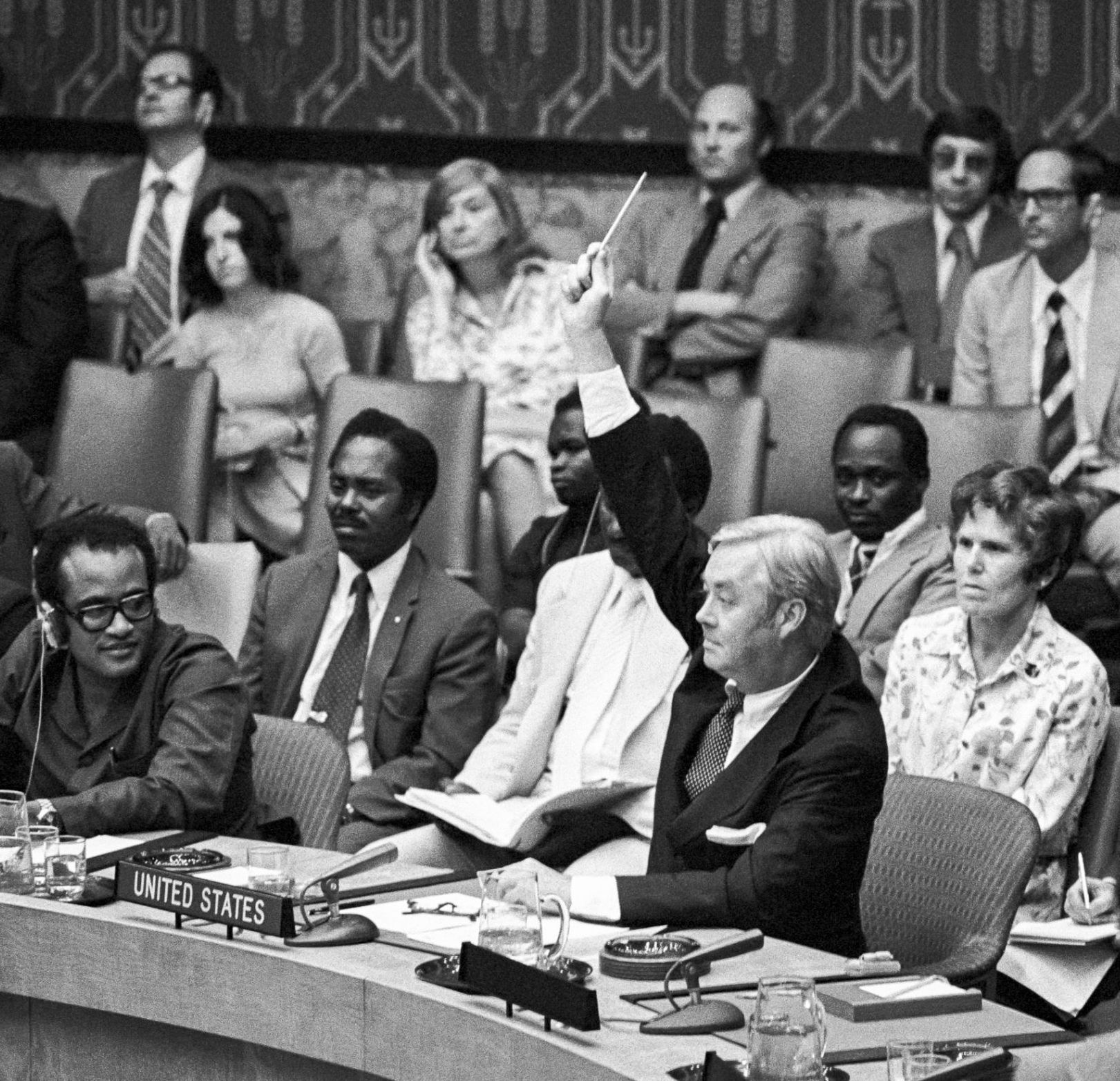

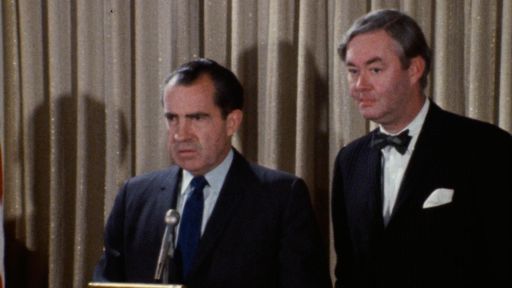

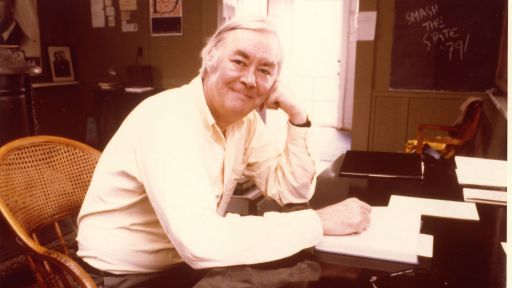

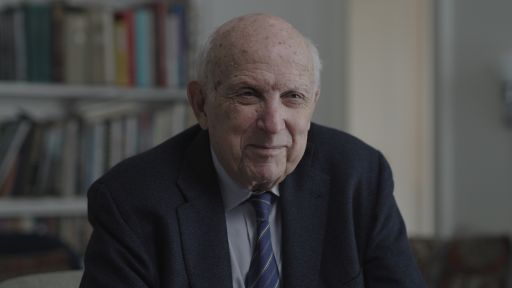

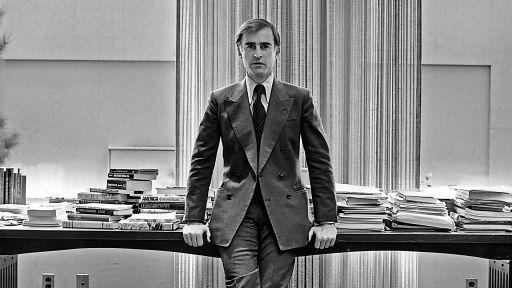

In 1969, Daniel Patrick Moynihan sent a one-page memo to a top Nixon advisor on “the carbon dioxide problem.”

What he wrote was a prescient early warning about the consequences of burning fossil fuels.

Moynihan wrote this just seven months before the first Earth Day, a year before the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, and almost 20 years before climate scientist James Hansen delivered his blockbuster congressional testimony declaring global heating was underway. The memo itself is an unusual time capsule from a time before political polarization over climate change had settled in, and serves as a reminder of what could have been. Moynihan’s letter has surprising resonance today, especially when broken down by its arguments.

It begins:

“As with so many of the more interesting environmental questions, we really don't have very satisfactory measurements of the carbon dioxide problem. On the other hand, this very clearly is a problem, and, perhaps most particularly, is one that can seize the imagination of persons normally indifferent to projects of apocalyptic change.”

—Memo by Daniel P. Moynihan, September 17, 1969

When Moynihan wrote this, climate change was still somewhat of a theoretical exercise. It was theoretical because time was still on the world’s side, and disaster wasn’t likely until some distant future. Scientists already had begun measuring atmospheric emissions in 1958 at Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii and were aware atmospheric CO2 was rising, and had. And they knew that would cause global temperatures to rise.

Kenai Fjords Bear Glacier 1909 and 2005: Glacier retreat is one of the most visible climate impacts in national parks. Credit: NPS Photo

Moynihan predicted that climate change would inevitably galvanize the public. What he got right is that climate change is a cross cutting issue that affects everyone and everything, including extreme weather, national security, food security, biodiversity, economic stability and global health.

What he got wrong was how it would seize public imagination.

Indifference has always been the bigger problem holding back political action. Climate change has consistently ranked lower in public polling compared to the economy and healthcare, though concern has been on the rise in the past few years as extreme weather trends have become impossible to ignore.

“The process is a simple one. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has the effect of a pane of glass in a greenhouse. The CO2 content is normally in a stable cycle, but recently man has begun to introduce instability through the burning of fossil fuels. At the turn of the century several persons raised the question whether this would change the temperature of the atmosphere. Over the years the hypothesis has been refined, and more evidence has come along to support it.” —Memo by Daniel P. Moynihan, September 17, 1969

We now know that over the same period scientists were refining their climate understanding, the fossil fuel industry was doing the same. As early as 1954, a coalition of oil and car manufacturing groups provided funding for some of the earliest work to study CO2 levels, and Exxon and other oil companies had early research teams studying global warming.

Climate change wasn’t a polarized issue until the fossil fuel industry helped make it one. Despite its own in-house research, the oil industry has spent decades promoting scientific misinformation and sabotaging political action.

“It is now pretty clearly agreed that the CO2 content will rise 25% by 2000. This could increase the average temperature near the earth's surface by 7 degrees Fahrenheit. This in turn could raise the level of the sea by 10 feet. Goodbye New York. Goodbye Washington, for that matter. We have no data on Seattle.” —Memo by Daniel P. Moynihan, September 17, 1969

The frightening world that Moynihan describes is one where climate change is left mostly unchecked. But this, and worse impacts, are not unfathomable. If the last few years of extreme weather have taught us anything, it’s that millions of lives can be upended at lesser levels of warming. The world still isn’t doing enough today to avert catastrophic impacts. Even if every nation fully implements its pledges under the Paris climate agreement, we are still likely to face 5 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius) of warming. So much hinges on delivering more ambitious emissions cuts. It’s why climate experts have taken to urging that every fraction of a degree matters.

Increased Fire in Mojave Desert: As temperatures warm certain invasive species, like buffelgrass thrive in the arid desert environment. This grass causes increased fires that threaten iconic native species of Joshua Trees and Saguaro cactus. Credit: NPS photo

“It is entirely possible that there will be countervailing effects. For example, an increase of dust in the atmosphere would tend to lower temperatures, and might offset the CO2 effect. Similarly, it is possible to conceive fairly mammoth man-made efforts to countervail the CO2 rise. (E.g., stop burning fossil fuels.)”

—Memo by Daniel P. Moynihan, September 17, 1969

The most interesting part of the memo is its clear moral clarity. To avoid this fate, the world will need to take “mammoth” steps, like stopping burning fossil fuels. A sign of how successful the fossil fuel industry’s misinformation campaigns were in subsequent years is that the “fossil fuels” themselves dropped out of political rhetoric altogether. In fact, the concept of transitioning away from fossil fuels was never seriously considered in international climate negotiations until 2023, the first time it was included in the final agreement.

“In any event, I would think this is a subject that the Administration ought to get involved with. It is a natural for NATO. Perhaps the first order of business is to begin a worldwide monitoring system. At present, I believe only the United States is doing any serious monitoring, and we have only one or two stations. Hugh Heffner knows a great deal about this, as does also the estimable Bob White, head of the U.S. Weather Bureau. (Teddy White's brother.)” —Memo by Daniel P. Moynihan, September 17, 1969

The short memo contains a surprising range of arguments that are still relevant today, including that climate action requires both political leadership and international cooperation.

Even in 1969 it was possible to imagine technologies (solar and electric cars among them) that could replace fossil fuels. Thanks to technological advancement, it’s become even easier to imagine a future without fossil fuels. Though we can’t correct for the wasted time derailed by fossil fuel misinformation campaigns and science conspiracy theories, we still have it in our power to take action today. The challenge, then as now, is one of political will.