For the past 20 years, British Ecologist Chris Morgan has worked as a wildlife researcher and educator on every continent where bears exist. From icy polar bear country at 81° North to tropical Andean bear forests sitting on the equator, Chris has sought adventure among the focus animals of his life — the bears of the world. Carnivore work has also taken him to the Canadian Rocky Mountains, Scotland, the Pakistani Himalayas, northern Spain, Turkey, and Alaska — destinations where his enthusiasm for wild places has rubbed off on others. Chris owns an ecology and environmental education business in Bellingham, Washington State. He is the creator and Co-Director of the acclaimed Grizzly Bear Outreach Project (GBOP) in the North Cascades. Chris is also a frequent lecturer at Western Washington University’s Huxley College of Environmental Science in Bellingham where he teaches ecology and environmental science classes. He has a B.S. in Applied Ecology (East London, UK) and an M.S. in Advanced Ecology (Durham, UK). In 2008 his contributions to grizzly bear conservation in the USA were honored with an award from the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee, a government panel responsible for recovery of the great bear. Chris is featured in the Nature films, Bears of the Last Frontier.

This interview was conducted by Inside Thirteen.

What first interested you in studying bears?

When I was 18, I came on a life-changing trip to the U.S. where I worked at a summer camp in New Hampshire designed to teach kids about conservation and wildlife. One day a bear biologist visited and I started to talk to him about the work he was doing in Northern New Hampshire. And I was hooked, more than any of the kids, I think! I just couldn’t believe that you could be a bear biologist in life. I bugged him for weeks and finally he relented and picked me up in his pickup truck one night and took me down to his study area. We pulled up outside this garbage dump, which had 14 black bears on it lit up by moonlight. It just blew my mind! I’d only seen one black bear in the forest near the camp prior to that. I spent the whole night tranquilizing and tracking these bears. It changed my life – I was set to become a graphic designer back in England.

How did you cope with being out in the wilds of Alaska for so long? What was the hardest part of the experience?

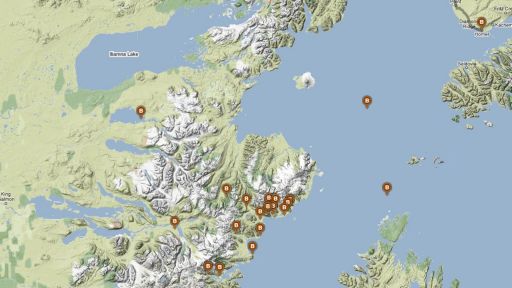

I was out there on and off for a year. There were times when Joe [Pontecorvo] and I were camping and isolated for weeks at a time, but I love that. I’ve spent a lot of time in the wild in very isolated places, but in our first location, the Alaska Peninsula, the density of bears is like almost nowhere else on Earth. What was unique about that for me was camping and being in that environment for so many consecutive weeks – it’s such an immersive experience in the bears’ world.

Some of the hardest parts were the misery of a long drive on a motorcycle. Once you’ve crossed the Arctic Circle, it’s a psychological milestone, but then realizing you’ve still got hundreds of miles to go before you reach the north coast of Alaska…it’s just a colossal place and it really is representative of these amazing, large wild animals that we were filming. The other thing I think people assume about film is that it’s glamorous and easy. We put a lot of hard work in and many, many sleepless nights in order to get the shots that we wanted. When we were filming bears in the northwestern part of Alaska, we were in an area were the western Arctic caribou herd is. We put in a heck of a lot of time looking for these half-million animals, so we could then find the bears. We ended up with lots of sleepless nights and just basically taking catnaps. Joe is a very hard worker – he’ll film as long as there is light, and that’s a problem when you’re in the Arctic in the summer, because there’s always light!

What are the key differences between the three types of bears?

They are three very distinct species. The bear numbers give away a lot about their personality. There are probably 35,000 brown bears in Alaska, and 180,000 black bears, so they’re a little bit more numerous and flexible around humans because there’s more of them. There are probably 2,000 or 3,000 polar bears, and those populations are also shared with Canada and Russia. There are much smaller numbers of polar bears because they are highly specialized and they feed exclusively on meat. The brown bears (also called grizzly bears) are the consummate generalists; they’ll eat everything from berries to Arctic root plants to a moose carcass, when they come across it. Black bears need forest, so where you have forest in Alaska, you’ve got black bears in good numbers. Brown bears will also inhabit forests, but they will extend above the tree line and into the Arctic where it’s just wide-open tundra and no trees in sight.

There are a lot of similarities in terms of behavior. Generally speaking, brown bears are more likely to become defensive and charge than black bears. Black bears are more likely to run in the opposite direction, even if they have cubs.

How did you make the bears feel comfortable in your presence? Have there ever been any incidents in your encounters where the bears were not so friendly or trusting?

In the case of the female with her cubs in the first episode, those cubs had never seen people before us. They’d just come out of their dens, and they were super inquisitive. They took it in like little sponges, like baby humans do. The cubs were playing around and the mother would just give them a stare or turn around while they’re running circles around her, like “alright, calm it down, don’t attract attention.”

On one occasion, a big male bear did charge us. He just got momentarily confused because a female ran behind us that he was chasing. I think he saw us as another bear – competition for his gal! He just charged right after us, and it’s a heart pumping moment. It’s not unusual for bears to charge people or other bears to give them a message, “hey you’re too close” or “you’re threatening me.” We’d not been doing any of those things, but they don’t talk, so they’ve got to express their concern in some way.

You have to take every possible precaution. I don’t approach the bears – if they graze past us, that’s a different thing. We were camping with electric fences around our tents – bear fences that zap 5,000 volts on a bear’s nose when it tries to come near your tent. Hopefully it doesn’t in the first place because the other thing you do is keep your kitchen and your food storage area a hundred yards away from where you’re camping. Never put food in your tent. You have to make sure the bear doesn’t relate you to food, because that can end in a dangerous situation, for the bear and for the people. I also carried bear spray the whole time. You never want to surprise any bears – make sure they know you’re coming, and that you shout out “hey, bear” every so often as you’re walking down the trail. Don’t threaten females with cubs, don’t approach a bear that’s sitting with a carcass of food – just common sense things.

What were you most surprised to learn during your observations in Alaska?

What really opened my eyes were the interactions between these bears during the breeding season, and how busy the place got. There are so many bears there, the females ended up being just as competitive as the males were for their love interests.

Overall though, I was surprised to learn how adaptable these animals are, and how different they all are. By the end of the third hour, it’s clear that any two bears you meet are as different as any two people you might meet. These are super smart animals, and because they’re smart they’ve got this ability to have different personalities and dispositions. They’re all individuals.

What was your favorite location you visited in Alaska? What has been your favorite place your adventures studying bears has taken you?

Probably my favorite place on the entire planet is the Alaska Peninsula. It’s like stepping back in time to 10,000 years ago. You could drop down at any moment, and it would feel the same. There aren’t many places in the world that feel that way. It’s one of the last really wild places that we have in the world and there’s something incredibly magical and special about that fact. You definitely feel like you’re the outsider when you’re there. Like it says in the film, it’s the bears’ world, we’re just visiting.

Svarbard, or some people call it Spitsbergen, is another one of my favorite places, in the European Arctic. It’s a Norwegian sovereignty – about 500 miles north of northern Norway. I’ve guided expeditions there for years to show people polar bears. It is mind-blowingly beautiful, like someone chopped off the Swiss Alps and plunked them in the middle of the ocean.

I love the north, and I’m drawn to the Arctic. The tropics are amazing, but for some reason I’m drawn to the coldest places because it makes you question your ability as a human, and you can’t help but respect a polar bear when he’s hunting seals in the pitch darkness all winter and it’s -40 degrees.

It is asked in this episode, “How much wild are people in Anchorage willing to tolerate?” How much of a threat to Alaska’s bear population are humans and the urbanization of Alaska’s wild? Is anything being done to protect them or keep them “wild”?

Anchorage is on the front line of what we call the wildlife-human interface. It’s where the wild ends and civilization begins. With a place like Anchorage, it’s like a dot of civilization in a sea of wilderness. There are wild animals in people’s backyards and on bicycle trails through parks in town and places where you’re perhaps not used to seeing a 1,000 lb brown bear or a moose or a black bear family. Most of the people in Anchorage are very accepting of having these wild neighbors and it’s partly why they live in Alaska. A lot of this Alaska pride comes through, like “Yes, we live in the wildest state in the Union.” It’s really refreshing. Sometimes things do go awry, where you’ll have a loose animal in someone’s backyard causing damage, or, in the worst-case scenario, you may have a person attacked by a bear. But it’s very rare considering the number of bears around. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game has a team that consists of the two people that are actually in our film – Jessy Coltrane and Rick Sinnott. Their job is being on the front line of where the humans and wildlife meet. Sometimes it means them going in and capturing bears or tranquilizing a moose and removing them from a situation where they’re really close to people.

It’s great, because we can use places like Anchorage as a model for co-existence with humans. It’s more of what this planet needs. These animals, in many parts of the world, are really highly threatened and in trouble. You look to Alaska and you feel like this is the last place in the United States where at least the near future is secure for these bears. I live in Washington State; we’ve got about 20 grizzly bears here. I work on that population and I work with members of the public in these rural towns in grizzly bear country to help them understand what grizzly bears are, what we need to do to have more of them here, how we can live with bears. I live that every day, so going to a place like Alaska is an eye opener in terms of the possibilities for a place that’s still got these large populations of animals. The window will always be open.