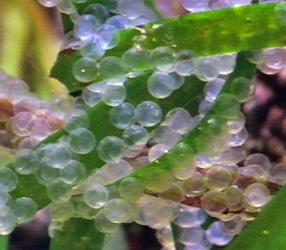

Herring eggs laid during the mass spawning. To make LIFE AT THE EDGE OF THE SEA, veteran British filmmaker Rodger Jackman had to figure out how to work amid the pounding waves, howling winds, and harsh weather that are the hallmark of British Columbia’s Bamfield Marine Station, headquarters of the production. “I knew it was going to be tough,” Jackman says. “You simply can’t take delicate cameras out into 20-foot waves that can deliver the force of a car driving into a brick wall at 90 miles per hour.”

In addition, Jackman notes, divers carrying cameras are often unable to approach many animals without scaring them off or dramatically changing their behavior — a major problem for a filmmaker interested in capturing a creature’s natural habits. So, to put his starring actors in a comfortable situation where they could be easily filmed, Jackman constructed an elaborate set of aquaria in a makeshift studio: the marine station’s boat shed. The largest, which was 10 feet deep and four feet wide, required more than a ton of sand and rocks and took about three days to build and stock with animals. “If you set up and maintain the tanks properly,” he says, “many animals will go about their business quite naturally.”

Most importantly, Jackman believes that working in a studio situation allows filmmakers to capture scenes that would be virtually impossible to record in the wild. For instance, a dramatic sequence in LIFE AT THE EDGE OF THE SEA shows immense schools of herring spawning in coastal waters, which become milky from the billions of eggs and sperm. “Once the spawning started, the water was so milky you literally couldn’t see the fish unless they swam up against the lens,” he remembers.

“So to complement the wild footage,” Jackman continues, “we put a relatively small school of fish in the big tank and then, when they started to spawn at about four in the morning, filmed them until they made even that tank too milky to see.” Using the aquaria, Jackman’s team was also able to capture the gracefully arcing jets of sperm and eggs released by sea urchins and the equally captivating mating habits of barnacles. Over the course of two years, the film was assembled by quilting intimate scenes together with footage that could be captured only in the wild, such as a 9-foot-long giant octopus snagging a crab in its tentacles and ghostly, soft-bodied nudibranchs drifting from kelp stalks.