Dr. Steve K. Windels, wildlife biologist for Voyageurs National Park, explains how national parks make critical conservation research possible and gives insight into the work being done with wolves at Voyageurs.

Photo: Tom Gable

Protected areas like Voyageurs National Park (VNP) have played an outsized role in wildlife conservation over the last 150 years. As human populations pressed forward across the globe, protected areas often preserved natural habitats and protected wildlife species within their borders that were otherwise threatened or decimated on the outside. For example, eastern mountain gorillas basically only now exist in a handful of East African parks. Protected areas can also serve as incubators for growing reintroduced populations of endangered species, such as black-footed ferrets in Wind Cave and Badlands National Parks in South Dakota.

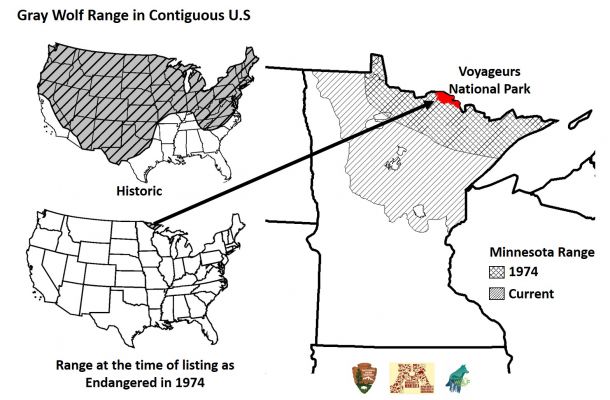

While gray wolves were largely exterminated from the Lower 48 States and Mexico by 1974 by predator control activities, wolves maintained their presence in northern Minnesota, including in the area that became Voyageurs National Park in 1975, continuing an 8,000-year streak of wolves howling in the Land of 10,000 Lakes.

In this case, persistence of wolves in the area owed as much to the large tracts of boreal forest habitat and proximity to source populations in nearby Ontario as it did to its designation as a protected area, but we remain proud of the fact that this part of northern Minnesota has always had wolves as integral parts of our ecosystems. And we take seriously our National Park Service charge to “conserve the scenery…and the wildlife therein and … leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations,” as described in the National Park Service Organic Act of 1916.

Referenced in the title of the influential PBS documentary series “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea,” the model of conservation through the designation of national parks (and other types of protected areas) requires more than just drawing a line on a map, though, in order to conserve wildlife and other biodiversity. It requires consistent monitoring to understand how many individuals are in the population, or whether the population is trending up, down, or staying the same. Such monitoring should also seek to understand how individuals or groups of animals move around within the park, or if and when they may migrate into and out of the areas of protection. A good monitoring program should also know birth dates or the causes of death of species of concern, and what the species eats and how much of that food is available on the landscape.

And so it is with the gray wolf population in Voyageurs National Park. When federal protection of wolves under the U.S. Endangered Species Act began in 1974, negative attitudes towards wolves were very common at that time in northern Minnesota. This was exemplified by a dead wolf being deposited on the front steps of the Voyageurs National Park headquarters in February 1977 by a group calling itself Sportsmen Only Solution (SOS), placed there as an admitted protest against federal regulation of wolves. Beyond the Endangered Species Act, the National Park Service implemented additional regulations and policies in place to ensure that wildlife species of concern like gray wolves were properly monitored to best direct its management actions. Wildlife biologist Dr. Glen F. Cole was the first one to start monitoring wolves in the park in 1977, mostly by conducting aerial pack counts in winter via the park’s airplane. He reported the first estimate of Voyageur’s wolf population as 32-35 wolves occupying the park or adjacent lands during the years 1977-1979. He later hired Research Wildlife Biologist Dr. J. Peter Gogan, who was charged with not only monitoring the park’s wolf population during the period 1987-1991 but also to better understand the dynamics of their primary prey, white-tailed deer and moose. The number of wolves utilizing at least part of Voyageurs National Park during this time ranged from 21-52.

Monitoring efforts continued throughout the 1990s and 2000s, a persistently tumultuous time in the park’s history when we were sued many times regarding management of wilderness and wildlife. Legal harvest has always occurred in adjacent Ontario, Canada, but the illegal killing of wolves that ventured outside of the park boundaries continued to be the primary cause of death of park wolves on the Minnesota side. The park also wrestled with balancing protection for federally threatened wolves and bald eagles in the park with recreational snowmobile use that was specifically authorized in the park’s enabling legislation. After many years of detailed study, it was deemed that snowmobiling was not negatively impacting the local wolf population, and all of the various lawsuits on the matter were either settled or dropped by the time I was hired in 2003 as the park’s Wildlife Biologist.

Having exceeded the population recovery goals outlined in the Gray Wolf Recovery Plan, gray wolves were officially delisted in Minnesota in December 2011, and management authority returned to the state. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Post-Delisting Monitoring Plan called for all federal land management agencies to conduct intensive monitoring to ensure that wolf populations remained stable after their return to state control. Thus was born the latest iteration of wolf monitoring in Voyageurs National Park, with the first wolf “V001” collared on October 3, 2012, near Ek Bay on Kabetogama Lake.

Legal harvest seasons for wolves in the northern part of Minnesota (but excluding Voyageurs National Park, where hunting and trapping are prohibited) were managed by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources in 2012-2014. Two wolves collared in or near VNP were legally harvested in Minnesota outside the park, and two others harvested in Ontario. Population monitoring continued during this period, with estimates of up to 48 wolves using parts of the park in 2014. A series of lawsuits lead to wolves in Minnesota (and other states) being relisted as federally threatened in December 2014, where they have since remained.

The most current chapter of wolf monitoring and research in VNP history has quickly proven to be the most productive. Through a collaboration with Northern Michigan University, a new M.S. student, Tom Gable, was brought on-board in the Fall of 2014 to begin more intensive studies of wolf-beaver interactions, including his exciting discovery of how wolves hunt and kill beavers. A second student, Austin Homkes, started his M.S. in Fall 2016 studying predation behavior on white-tailed deer fawns; he now works as a wildlife technician for VNP. Based on the success of the project, we were able to secure funding from Minnesota’s Environmental and Natural Resources Trust Fund to expand our efforts to understand summer wolf predation behavior and the effect of wolf predation on prey populations of beavers, moose, and deer. Co-mentored by Dr. Joe Bump (University of Minnesota Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology) and myself, Tom Gable began his Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota on the project in Fall 2017, where he continues to advance wolf science and conservation through his studies and outreach.

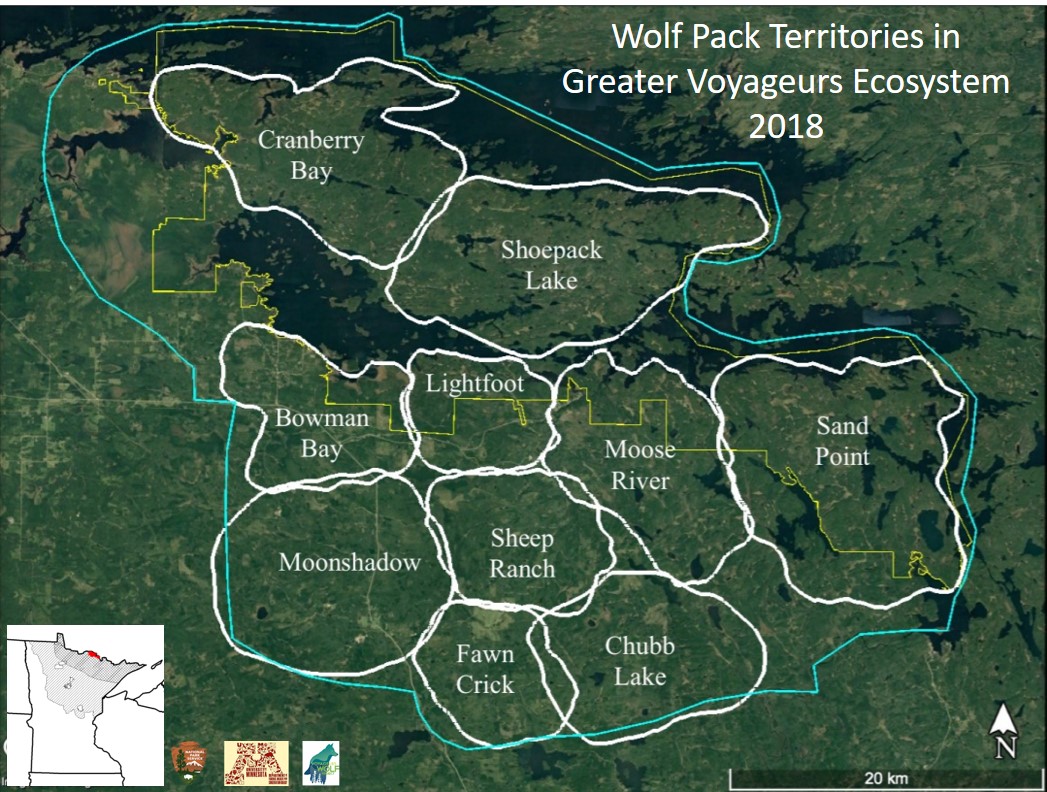

This new phase in the history of wolf monitoring and science at Voyageurs National Park has been dubbed the Voyageurs Wolf Project (VWP), defined by its unique collaboration between Voyageurs National Park biologists Homkes and Windels and University of Minnesota researchers Gable and Bump.

The VWP aims to study the ecology of wolves and their prey (moose, deer, and beavers) during the summer in the Greater Voyageurs Ecosystem, which comprises Voyageurs National Park and the adjacent lands. Thanks largely to Tom Gable, the VWP now has a large social media presence on Facebook and other platforms that seemingly grows by the day. Having our research featured on PBS Nature’s American Spring Live on May 1 should only increase our project’s reach!

Since that first wolf in 2012, we’ve now captured 73 more wolves as part of the Voyageurs Wolf Project, making it the longest and most extensive period of monitoring in park history. Our most recent estimates of wolves using parts of Voyageurs National Park range from 28-32. In March 2019, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service again proposed to declare wolves in the Great Lakes states as recovered and remove them from the Endangered Species List. If and when this happens, we will be even better positioned than last time to conduct intensive monitoring to ensure that future generations will be able to enjoy the howl of a wolf in Voyageurs National Park and beyond.