By Fiann Smithwick, scientific consultant for Attenborough and the Sea Dragon

One of the most important features of animals is their color. Whether it be to attract a mate or hide from a predator, color is involved in most aspects of animal behavior and influences how well they survive and pass on their genes to future generations.

Computer-generated image of a brand new species of an Ichthyosaur discovered in Lyme Regis, UK. Scientists believe that this is the most scientifically accurate depiction of an Ichthyosaur ever.

Color is, therefore, key to animal evolution. This becomes obvious when you look at the range of colors in living animals. Color is not just important for living animals however, it was undoubtedly also important for animals in the past and has likely been ever since the evolution of the eye over 500 million years ago. Once thought impossible, scientists can now tell what colors many extinct animals may have been.

Living animals often color themselves using pigments, organic compounds that absorb and reflect specific colors. The most common of these pigments is melanin, which gives color to human skin and hair, as well as the hair of other mammals, feathers of birds and skin of reptiles and amphibians. Luckily for paleontologists, melanin can be preserved in rare cases in fossils. In vertebrates, melanin is packaged in tiny structures called melanosomes. It is these melanosomes that are found in fossils and can tell us about the color of extinct animals.

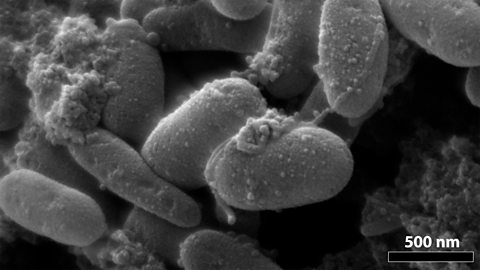

Melanosomes preserved in the skin of the ichthyosaur, imaged using an electron microscope and magnified 90,000 times.

By looking at melanosomes preserved in the feathers and skin of some spectacular fossils, palaeontologists have been able to reconstruct the colors of some dinosaurs. We now know for example that some dinosaurs had stripy tails and face masks, spotted wings, and even iridescent bodies.

In our ichthyosaur, we were able to look at the melanosomes preserved in the skin using a very high-powered electron microscope. To do this, pieces of the skin had to be removed from the fossil and coated in a thin layer of gold, which reduces the build-up of static charge in these powerful microscopes. This allowed us to see the microstructure of the skin and revealed countless tiny melanosomes, each measuring less than one-millionth of a meter across.

A piece of the very dark skin of the ichthyosaur removed from above the backbone.

Importantly, the melanosomes were not distributed evenly across the body of our ichthyosaur. The skin from the dorsal side of the animal (the back) was darker and had a lot of melanosomes preserved. The skin from the ventral side (its belly) was much lighter and did not have many melanosomes preserved. This tells us that our ichthyosaur most likely had a dark back and light belly, known as a countershaded pattern that is seen in lots of living marine animals like dolphins and sharks and is thought to be a kind of camouflage to help the animals blend into the background. This gives us a unique insight into not only what these long-extinct animals looked like, but also how they may have behaved.

Fiann Smithwick is a PhD student at the University of Bristol working on colour reconstructions in extinct animals. For more information about fossils and his work, follow him on Instagram (@fms.fossils) or Twitter (@Fiann_Smithwick).