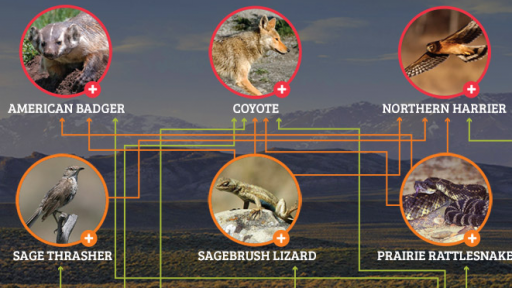

A scene from NATURE “The Sagebrush Sea”.

Editor’s Note: The following is a guest post from ecologist Holly Copeland, a staff scientist with The Nature Conservancy. Copeland’s work focuses on mapping out wildlife migration corridors and other important natural areas and then forecasting how future development will impact the landscape.

PBS NATURE’s The Sagebrush Sea, is an exquisite film that offers an unprecedented glimpse into the complex and abundant life within the sage. With the region once again facing an uncertain future, awareness about the struggles around this vibrant ecosystem is paramount.

Nature documentaries are typically about rainforest, arctic, and savannah ecosystems–strangely sagebrush has been largely overlooked as an empty landscape between lush and beautiful mountain ranges. It’s a perception that couldn’t be further from the truth given that approximately 350 species depend on sagebrush.

Filmed largely in Wyoming where nearly 40% of the sage-grouse population resides, the documentary features showy displays of male grouse as they compete for females at communal breeding sites called leks, the trials of a hen raising a successful brood, migrating mule deer, and the rearing of a golden eagle chick.

This film comes at a crucial moment for our sagebrush heart of the West.

An ecological transformation has been taking place across Western sage for centuries. Since the 1800s, we brought cattle and machinery for ranching, farming, and mining. Through heavy, prolonged grazing and the introduction of non-native grasses, we altered the natural balance between sage and the native bunchgrass and plants and changed the natural fire cycle.

To satiate our thirst for energy, we mined coal and drilled and fractured rock thousands of feet beneath the earth for gas and oil. This energy is shipped out to populations reaching all the way out to our coasts. Flip on a light Watch the meter run anywhere in the United States and there is a reasonable likelihood that at least some of that electricity was produced in the West.

While we all use energy, we also know its production has consequences. One of the unintended consequences has been a decline of native plants and animals in sagebrush ecosystems.

Sage-grouse, in particular, are dependent on sagebrush throughout their life cycle and thrive in large, unfragmented expanses of sagebrush. We know without question that grouse avoid habitats with increasing oil well density and associated roads, industrial activity, and are affected by increasing levels of noise.

Due to estimated range-wide declines of 60% (2% per year) since 1965, sage-grouse are now under consideration for listing under the Endangered Species Act. The potential listing decision has sparked a national debate on threatened species and how best to conserve them. Most states have crafted sage-grouse conservation strategies to prevent a listing.

While our collective effort to protect sage-grouse to date is laudable, millions of acres of sagebrush are already leased for oil and gas, and thus likely to see more fragmentation. And, while restoration efforts abound, restoration of sagebrush is extremely difficult, especially in the aridest regions. In some places, restoration may not really be possible at all.

On the flip side, hope for the sagebrush ecosystem is everywhere.

Teams working on restoration have made intriguing progress, such as in Douglas, Wyoming where thousands of sagebrush plants have been patiently grown in greenhouses and planted in an effort to restore lands from a wildfire.

Regional planning efforts are underway throughout sage-grouse range, and where implemented have resulted in commitments by industry to do more to mitigate their impacts and to improve range conditions.

Strategic efforts by the Sage-Grouse Initiative are working to restore juniper encroached areas, improve grazing practices and secure conservation easements to benefit both grouse and mule deer. All told, they’ve partnered with over one thousand ranchers and enhanced 4.4 million acres, an area that is twice the size of Yellowstone National Park.

And finally, there is the promise of distributed solar energy as a truly transformative technology that can shift our need away from large-scale industrial energy to rooftop systems that provide the energy we need without fragmenting and polluting our remaining intact lands and waters. Stories emerge daily about companies and families large and small, including my own, reaping the economic benefits of solar.

My great hope is that this film will elevate the national conversation about our sagebrush land and that better understanding will motivate the public and our leaders to conserve the remaining intact sagebrush and use the best science to manage grazing and to guide restoration efforts.

We have arrived at a profound moment in the era of Western conservation, a test of whether we truly have the willpower to preserve the remnants of our American natural heritage. It will require cooperation, meaningful and open dialogue, acting in good faith, and hard choices. We must resist pressure to ignore leading science when it is not convenient.

We are amidst a shift in consciousness, “the great turning,” as ecologist Joanna Macy calls it. A new generation is ready to meet these challenges with new tools and to do things differently than in the past. In that sense, the sage-grouse strutting in front of a well at the end of the film, if it knew, would have every reason to be hopeful for the future to come, as am I.

References:

Baruch-Mordo, S., J. S. Evans, J. P. Severson, D. E. Naugle, J. D. Maestas, J. M. Kiesecker, M. J. Falkowski, C. A. Hagen, and K. P. Reese. 2013. Saving sage-grouse from the trees: A proactive solution to reducing a key threat to a candidate species. Biological Conservation 167:233-241.

Blickley, J., Blackwood D, and G. Patricelli. 2012. Experimental evidence for the effects of chronic anthropogenic noise on the abundance of Greater sage-grouse at leks. Conservation Biology 26:461-471.

Boyd, C. S., J. L. Beck, and J. A. Tanaka. 2014. Livestock Grazing and Sage-Grouse Habitat: Impacts and Opportunities. Journal of Rangeland Applications 1:58-77.

Braun, C. E. 1998. Sage grouse declines in western North America: what are the problems? Proceedings of the Western Association of State Fish and Wildlife Agencies Pages 139-156.

Carpenter, J., C. Aldridge, and M. S. Boyce. 2010. Sage-Grouse Habitat Selection During Winter in Alberta. Journal of Wildlife Management 74:1806-1814.

Connelly, J. W., and C. Braun. 1997. Long-term changes in sage grouse Centrocercus urophasianus populations in western North America. Wildlife Biology 3:229-234.

Connelly, J. W., S. T. Knick, M. A. Schroeder, and S. J. Stiver. 2004. Conservation assessment of greater sage-grouse and sagebrush habitats. Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, Cheyenne, WY.

Copeland, H. E., H. Sawyer, K. L. Monteith, D. E. Naugle, A. Pocewicz, N. Graf, and M. J. Kauffman. 2014. Conserving migratory mule deer through the umbrella of sage-grouse. Ecosphere 5(9):1-16.

Davies, K. W. 2011. Plant community diversity and native plant abundance decline with increasing abundance of an exotic annual grass. Oecologia 167:481-491.

Davies, K. W., C. S. Boyd, J. L. Beck, J. D. Bates, T. J. Svejcar, and M. A. Gregg. 2011. Saving the sagebrush sea: An ecosystem conservation plan for big sagebrush plant communities. Biological Conservation 144:2573-2584.

Doherty, K. E., D. E. Naugle, B. L. Walker, and J. M. Graham. 2008. Greater Sage-Grouse winter habitat selection and energy development. Journal of Wildlife Management 72:187-195.

Dzialak, M. R., C. V. Olson, S. M. Harju, S. L. Webb, and J. B. Winstead. 2012. Temporal and hierarchical spatial components of animal occurrence: conserving seasonal habitat for greater sage-grouse. Ecosphere 3:art30.

Gilbert, M. M., and A. D. Chalfoun. 2011. Energy development affects populations of sagebrush songbirds in Wyoming. The Journal of Wildlife Management 75:816-824.

Holloran, M. J., and S. H. Anderson. 2005. Spatial distribution of Greater Sage-Grouse nests in relatively contiguous sagebrush habitats. Condor 107:742-752.

Patricelli, G., J. Blickley, and S. Hooper. 2013. Recommended management strategies to limit anthropogic noise impacts on greater sage-grouse in Wyoming. Human-Wildlife Interactions 7:230-249.

Sawyer, H., R. M. Nielson, F. Lindzey, and L. Mcdonald. 2006. Winter habitat selection of mule deer before and during development of a natural gas field. Journal of Wildlife Management 70:396-403.

Walker, B. L., D. E. Naugle, and K. E. Doherty. 2007. Greater sage-grouse population response to energy development and habitat loss. Journal of Wildlife Management 71:2644-2654.

Wisdom, M. J., M. M. Rowland, and L. H. Suring, editors. 2005. Habitat threats in the sagebrush ecosystem: methods of regional assessment and applications in the Great Basin. Alliance Communications Group, Lawrence, Kansas, USA.