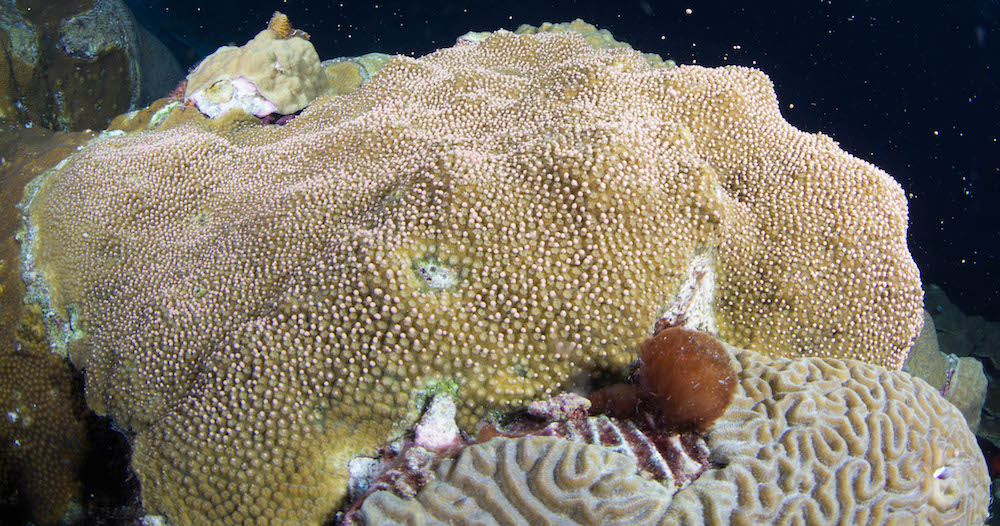

Photo was taken during the first spawn, August 3-5. Image courtesy NOAA Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary.

Just after sunset in early August, divers descend into inky black waters of the Gulf of Mexico, 100 miles from shore. The beams of their dive lights pierce the darkness, illuminating a large coral mound, its textured surface covered in tiny white dots. At some unseen signal, the dots begin to rise toward the sea surface, some 70 feet above.

Here in the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, seven species of corals participate in this mass broadcast spawning, or release of eggs and sperm into the water, from seven to ten days after the August full moon.

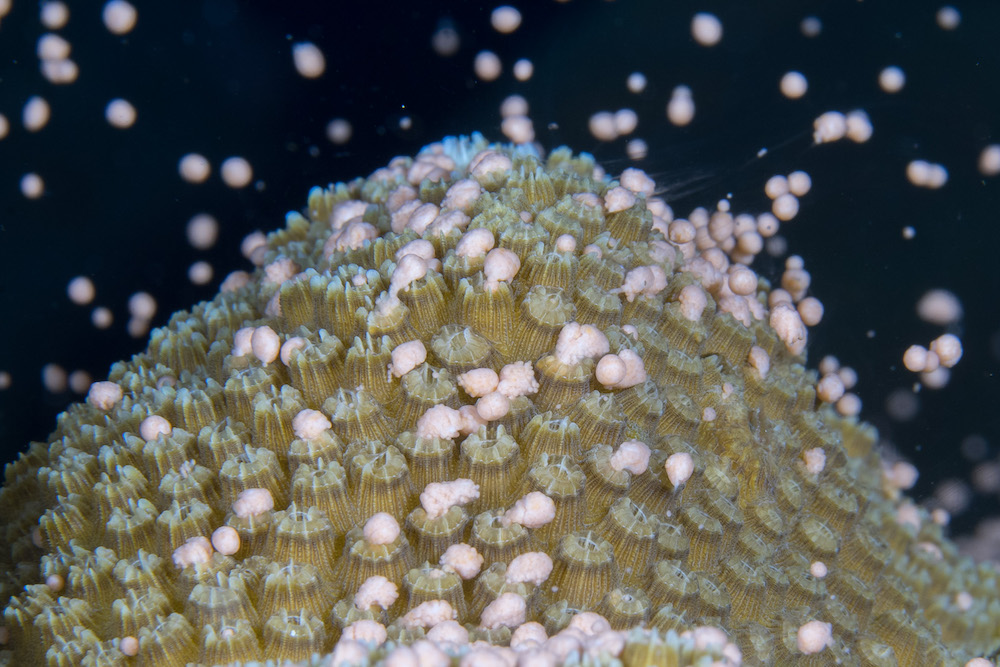

Members of a particular species spawn simultaneously for up to an hour, followed a brief time later by another species and another after that. This frenzy of reproductive activity clouds the water, eggs rising like upside-down snowfall, sperm like plumes of smoke. In the right conditions, the sheer quantity forms a slick on the surface, where the real action – fertilization – occurs.

Seeing this unique sight requires scuba diving at night in the remote Sanctuary during just the right window of time. People have done far more difficult things for love, and the M/V Fling, a dive charter boat that frequents the Flower Gardens, books solid for the coral spawn.

This summer featured two coral spawning events, one in early August following full moons in late July and another in early September after a late August full moon, according to Sanctuary researcher coordinator Emma Hickerson.

Image courtesy NOAA Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary.

In addition to moon phase, water temperature plays a major role in the timing of the mass spawning here and at other coral reefs around the planet. A 16-year study of more than 80,000 coral colonies found that spawning coincided with the largest month-to-month increase in sea surface temperatures.

Reef-building corals consist of thousands of tiny, tentacled polyps inside skeletons of calcium carbonate, each connected by a thin layer of tissue. Coral colonies grow through asexual reproduction, where polyps bud or split into new, genetically identical polyps. Sexual reproduction creates genetically unique offspring, and broadcast spawning generates new coral colonies as larvae drift on ocean currents to new homes. The Flower Garden reefs likely started when larvae drifted here from reefs off of Tampico, Mexico.

Image courtesy NOAA Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary.

Whatever the exact trigger, the everyone-at-once spawning likely increase the odds of eggs and sperm actually bumping into each other in the open water. In addition, the sheer volume of reproductive effort ensures that at least some don’t merely become fish food.

The Flower Garden spawning occurs more or less in the same order every year, Hickerson says, generally beginning on the seventh night after the full moon, with Giant Star, Boulder Star, Symmetrical Brain and, finally, Blushing Star coral. Over the next several nights this sequence repeats but with significantly more colonies participating, with Mountainous Star and Boulder Brain coral joining in. Lobed Star coral also spawns intermittently throughout the event.

Sanctuary scientists have monitored the spawning since 1991 and consider it an important indicator of the reef’s health. After all, it’s hard to party (or reproduce) when you’re under the weather.