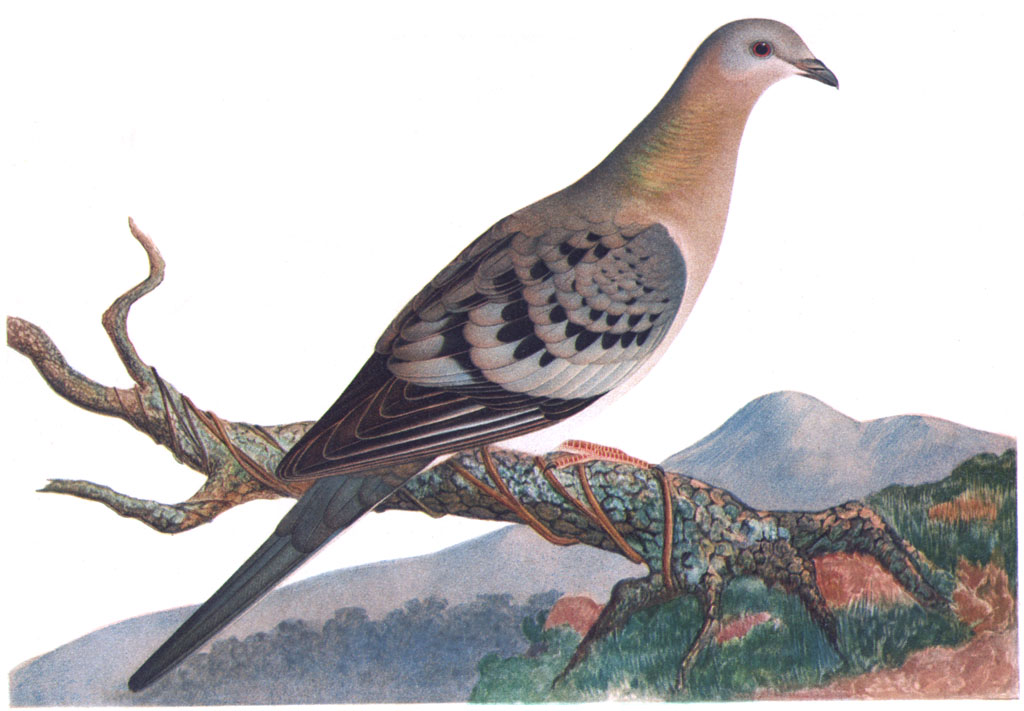

The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius). | Credit: Hayashi and Toda

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from “The Unnatural World: the Race to Make Civilization in Earth’s Newest Age” by journalist and broadcaster David Biello. The excerpt is from a chapter that describes a ‘de-extinction’ talk given by biologist Ben Novak and others at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Novak’s plan is to bring back the passenger pigeon, an iconic American species—once numbering in the billions—that was hunted to extinction.

Wildness today requires a deliberate act of human will, either to refrain from filling in a marsh in pursuit of another neighborhood or to actively restore what is now missing. Under the rubric of rewilding or just plain old restoration, wolves have been reintroduced to the western United States, beavers have been brought back to Britain after a 500-year absence and, maybe, one day, mammoth will again roam the Siberian tundra after disappearing for 4,000 years.

This is not an idea everyone cheers. Many people are happy with animals only as long as the animals don’t get in the way, serve a definitive purpose like lab rats, or function as entertainment, either cute animal videos on the Internet or nature porn, a twisted reflection of life outside human concerns that nonetheless at least can inspire some people to care. And then there are the ecologists who care deeply but note that nature in some of these depauperate places has adjusted to the absence of missing animals or plants, and reintroducing them may fulfill some dimly understood human need but does not constitute restoration. In fact, rewilding may wreak havoc on the world as it is today in ways that are unpredictable. The only thing scientists know for sure about biology and ecology is how little they know—and how little can be predicted. “An insect is far more complex than a star,” the astronomer Martin Rees likes to say.

The human relationship with wild animals in the Anthropocene has taken a turn toward the bizarre, the baroque late phase of decadence. On the one side, ardent conservationists are laying down their lives (and paying others to do so as well) to protect the dwindling herds of forest elephants in central Africa. On the other, game wardens in Romania feed brown bears so that other people can come and shoot them. As journalist David Quammen writes in Monster of God: “The gamekeeper’s role, visa-vis his resident bears, combines the services and attitudes of a nanny, a zoo attendant, a field naturalist, a sniper’s spotter, and a pimp.” Similar relationships exist from the Karoo of South Africa to the icy wastes of Alaska, where big-game hunters pay big bucks to hunt an animal that has been kept alive specifically for that purpose. Cecil the Lion died, provoking international outrage, so a dentist could have a trophy. Meanwhile, people starve in Zimbabwe.

Such passion for hunting is both why the passenger pigeon is now extinct and why it may not be the first bird to benefit from the tools of synthetic biology. The houbara and its resplendent plumage is the favored target of oil sheikhs. And the Saudis, who love the bustard, have the money to spend to save it from themselves thanks to the modern world’s addiction to oil.

Or perhaps the heath hen may beat the passenger pigeon to revival, pulling on the deep pockets of the residents of Martha’s Vineyard, where they finally went extinct. Then again, the pigeon business is worth hundreds of millions of dollars globally thanks to humans known as fanciers. If even a fraction of those who fancy pigeons can be engaged in bringing back the passenger variety with their discretionary dollars, “We’re home free,” as Long Now’s Ryan Phelan puts it.

The human instinct to hunt, which helped bring down the mammoth and the giant kangaroo, may be the last thing saving big mammals now. Hunters are the original conservationists and remain responsible for the majority of wilderness and wildlife protection the world over, like Wetlands International protecting unloved marshes for their value to duck hunters. The American bison was saved from slaughter by a captive-breeding program at the Bronx Zoo so that it could be hunted again. The auctioning off of a license to hunt an endangered white rhino raised money to preserve his fellows (as well as the ire of strict preservationists). Similar instincts expressed as aristocratic privilege have preserved wilderness areas such as the forests of Romania that house Europe’s largest population of bears thanks to the hunter’s lust of mad dictator Nicolae Ceauseşcu. The sacrifice of a stag or bear each fall to a hunter’s weapon can preserve both the natural character of the land as well as all the other inhabitants of the forest, as I can attest from family trips to the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont for deer hunting, where the real trick is not shooting a deer but getting a carcass out of the woods without roads.

The human instinct to hunt, which helped bring down the mammoth and the giant kangaroo, may be the last thing saving big mammals now. Hunters are the original conservationists and remain responsible for the majority of wilderness and wildlife protection the world over, like Wetlands International protecting unloved marshes for their value to duck hunters. The American bison was saved from slaughter by a captive-breeding program at the Bronx Zoo so that it could be hunted again. The auctioning off of a license to hunt an endangered white rhino raised money to preserve his fellows (as well as the ire of strict preservationists). Similar instincts expressed as aristocratic privilege have preserved wilderness areas such as the forests of Romania that house Europe’s largest population of bears thanks to the hunter’s lust of mad dictator Nicolae Ceauseşcu. The sacrifice of a stag or bear each fall to a hunter’s weapon can preserve both the natural character of the land as well as all the other inhabitants of the forest, as I can attest from family trips to the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont for deer hunting, where the real trick is not shooting a deer but getting a carcass out of the woods without roads.

This kind of ambivalent relationship to wildlife is likely to be a hallmark of the Anthropocene. Some, like Novak, will be dedicated to preserving or bringing back certain animals or plants. Others will be equally dedicated to killing them. Some of the most enthusiastic speculation around the TEDx de-extinction event came from readers of Field & Stream, who debated online which animal would be best to bring back to be hunted anew. The writer plumped for the heath hen, but the nominations included everything from the woolly mammoth to the Irish elk. Just imagine a mammoth’s head on your wall or an image of it huffing and puffing down the trail captured on camera. Human purposes, whether of care or carnivory, remain paramount.

Humans are the world’s worst invasive species, spreading out of Africa like a weed and proliferating wherever we go. Perhaps people hate our fellow invasives so much because they highlight our own flaws, much as parents tend to loathe any sign of their own worst traits in their children. We spread new life around the planet—wallabies living in a suburban forest outside Paris and the parakeet flocks of Brooklyn. The animals we’ve chosen thrive—the global livestock herd is now 50 billion animals. And synthetic biology isn’t just about repairing what has been torn in Earth’s great biology, it’s also about speeding the rate of creation—and directing it toward new ends.

The best news for the passenger pigeon is that its old habitat is growing back and growing in extent. The eastern woodlands have returned as farms fade away or move west to more fertile ground—in the past decade, 40,000 square kilometers of forest have regrown. That has brought back deer, coyotes, turkeys, raccoons, and even black bears in abundance. There is a home for the passenger pigeon and one of its dance partners of old, the chestnut; although eliminated by an invasive fungus from China, it may beat the bird back to the forest thanks to some similar genetic engineering efforts.

In the 1800s, the chestnut was even more abundant than the passenger pigeon, making up an estimated one out of every four trees in the Great Eastern Forest of North America that then covered the lands between Quebec and Florida and west almost to the Mississippi River. That’s at least 3 billion trees, or roughly one for every passenger pigeon. But imports of Asian chestnut trees brought along a fellow traveler—a fungus commonly known as chestnut blight. The American version of the tree had no defense. Within decades, the chestnut was gone, killed off by humans, just like the passenger pigeon.

The same genetic engineering that might bring back the passenger pigeon has been used to create an American chestnut tree with the genes from the Asian variety that enable the tree to survive the blight. All that stands between the new chestnut and its return to the regrowing forest is federal approval for the release of a genetically modified organism. “You and your children and your grandchildren need to help with this because it’s going to take a long time to bring it back,” says the forest biologist William Powell of the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry, who is leading the effort.

Plants should come first, since the passenger pigeon might not survive in the wild without chestnuts to eat. Plants make up 99 percent of living matter on the planet and provide all the food with the subtle trick of turning sunlight to sustenance via photosynthesis.

The redwoods that make Santa Cruz’s campus unique may even need help. Walking among them on the soft duff amid the curling fern fronds, it is impossible not to feel the pull of a druidic sacred grove—as well as big lumber. This is an entirely human-made felling, grottoes sculpted by the hands of people. But our genetic tools are, as of yet, ill suited to the complexity of plants. The genome of a tree can have 22 billion base pairs, or seven times as much genetic information as a person—and we barely even know ourselves genetically.

Even if the genetics work out someday, it will be very hard to reintroduce anything even resembling a passenger pigeon back into the wild, as the chestnut example proves. The Wildlife Conservation Society, heirs of an effort that saved the American bison at the turn of the twentieth century, now has a confiscated flock of band-tailed pigeons and is working to train them as a potential host for any resurrected passengers. Fortunately, humans have a lot of experience doing weird stuff with birds, like ultralights teaching cranes to migrate and puppets feeding baby condors. Novak’s plan is to dye his band-tailed pigeon parents, so that the chick can see a cosmetic replica of itself. Actual passenger pigeons were not good parents, however. “They abandon their young before the babies can even fly,” Novak notes. “ ‘Oh, you’re fat enough. Goodbye.’ ” That’s not rare among animals, but it is rare among birds, and no self-respecting band-tailed pigeon would ever do such a thing.

How do we make that adult flock so they migrate like they used to? Training homing pigeons, also painted, to teach the baby passengers where to take a ride to, from late autumn roosts in upstate New York down to southern forests, suggests Novak. Maybe we’ll even train the passengers to go to different spots than the historical record suggests, thanks to the climate change that took hold during their time away. Such assisted migration may prove vital in any human bid to preserve many species, not just resurrected ones.

Then there’s the question of law. Is a resurrected passenger pigeon—once there is even one—automatically put on the endangered species list? Or is it a GMO and therefore faces regulation before it can be put into the wild, like the American chestnut? As the title of a provocative paper put it, the biggest challenge facing any resurrected species may be “How to Permit Your Mammoth.”

© 2016 by David Biello. Published by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Reprinted with permission.