Male fig wasps inside a fig’s synconium, the fleshy, hollow receptacle that contains its flowers. | Courtesy of Vincent Savolainen

You’ll never see a fig’s flowers until you open one up. Unlike a blossoming plum, apple, or pear tree, figs hold their many microscopic white blooms inside of plump pouches at the end of their stems. On the tip of each pouch, there’s a small opening perfectly sized to host the tree’s only pollinator: the fig wasp.

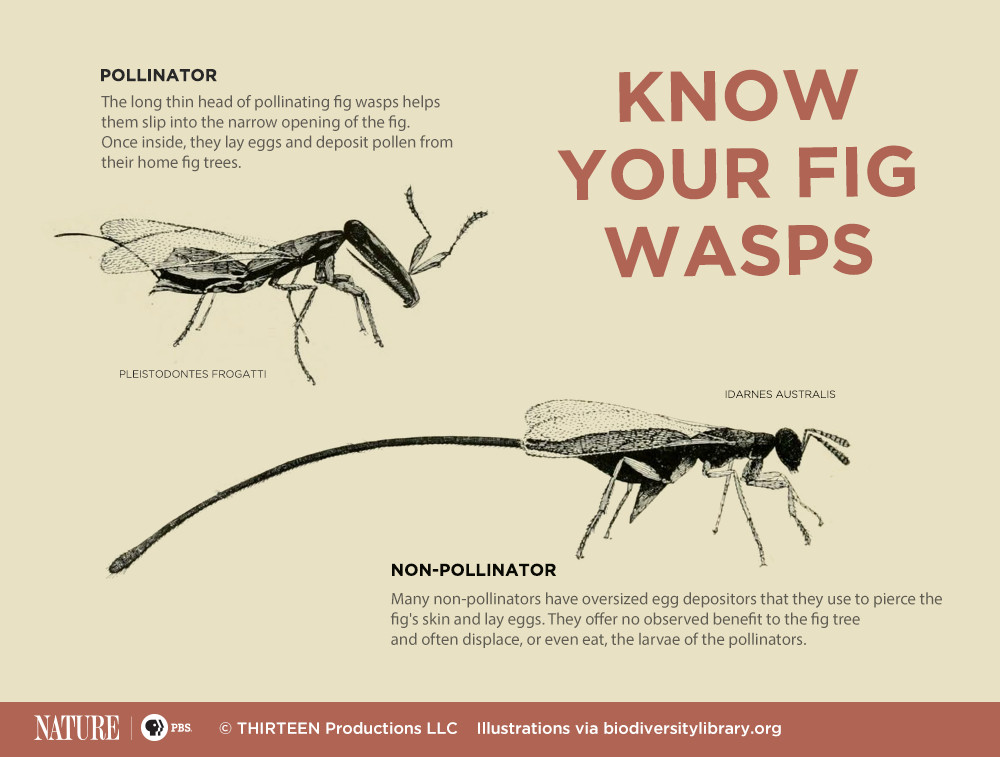

The female fig wasp, of the Agaonidae family, is a bland, black insect so tiny that she could slip through the eye of a needle and is drawn to the fig’s sweet chemical scent. Her long, thin head allows her to enter the fig’s small opening and lay her eggs. In exchange, the wasp brings pollen from the fig she was born in, to fertilize the tree. “She’s the only insect that can fertilize the fig’s inner garden,” says Fernando Henrique Antoniolli Farache, an entomologist at the University of Sao Paulo.

However, this dreamy symbiosis has long been getting hacked.

In 2008, Farache helped discover the oldest-known fossil of a non-pollinating fig wasp – Idarnes thanatos. The picayune insect was found encased in a piece of amber dated at 15-20 million years old; its discovery was published in The Journal of Natural History earlier this summer. (For comparison, the oldest-known pollinator, dated at around 34 million years old, was discovered almost a century ago, though researchers thought it was an ant until 2010.)

Farache’s team could tell that their tiny specimen was a non-pollinator thanks, in part, to the lengthy egg depositor on the wasp’s rear end. Non-pollinating wasps use this appendage to pierce straight through the fig’s green to purplish skin and inject their own eggs, which then develop in place of the fig’s seeds or the pollinating wasp eggs themselves. “Some non-pollinating wasps will directly attack the pollinators,” says Farache, “they may eat the pollinator wasps’ larvae or eat their food [the flower’s ovary], which leads to the pollinator larvae starving to death!”

Whether laid by a pollinator or ‘hacker’, over the next month or so, each egg will develop into a full-sized fig wasp. Nearly 95 percent are females. They soon gather pollen from their figs, and exit through holes cut out of the fig’s flesh by their brothers.

Male wasps are born without wings and with poor eyesight. That’s because they don’t need either of them. They’ll live just long enough to mate with the females, cut their escape holes, and then die in the fig’s fleshy garden. Yes, this means that when you eat a fig, you are also eating a burial grounds of (mainly male) corpses. “Most figs in the world have got wasps or remains of wasps left in them,” says ecologist Allen Herre of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institution. Though by the time the fig ripens, he said, the wasps’ bodies have mostly been digested by proteins in the fig.

Across the fig tree’s range there exist some 10,000 living species of fig wasps as well, says Farache — “that’s about the same number of birds that live in the world!” Of these, just over two thousand are pollinators. The rest, some 8,000 species of wasps, are all non-pollinators that utilize, but do not benefit the fig.

Clearly, fig wasps have discovered several ways to further their genes without helping their host. After all, says Herre, “If there is a way to make a living, nature is probably going to find it.”

Note: Figs that are commercially cultivated are generally a variety of the ancient common fig (Ficus carica) that do not require cross-pollination to produce ripe figs. This means, there are likely no wasp corpses to be found in the figs from your grocer.