Among biologists, it’s not uncommon to share photographs of interesting backyard finds – a salamander under the woodpile, for example, or an ant mound dug up by foxes. When traveling, the featured sights and species become more exotic. In lieu of standard vacation selfies, I’ve received snapshots of everything from stick bugs to sloths to quirky scientific curios. A friend visiting Kew Gardens in London once excitedly sent out images of dried plant specimens originally collected by Charles Darwin.

Photo via Washington State Department of Agriculture

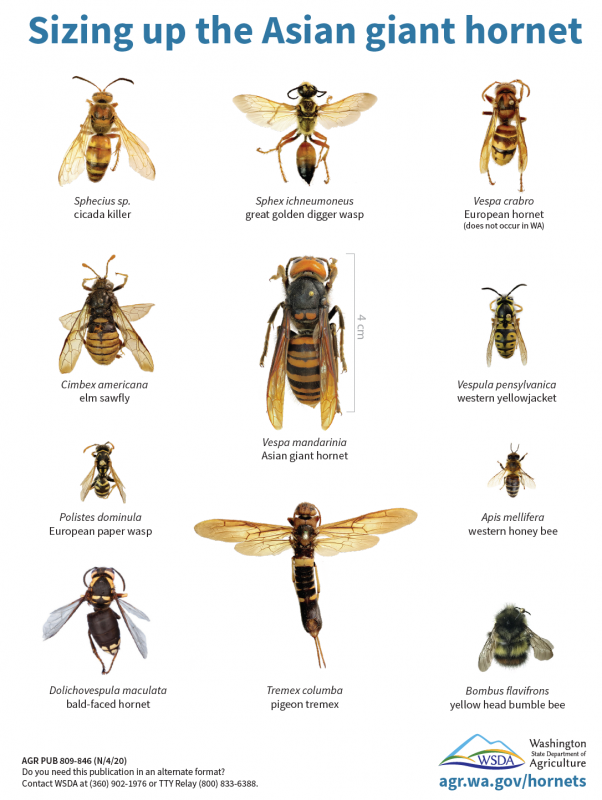

So nothing seemed out of the ordinary in late March, when I opened up an email containing pictures of an Asian giant hornet. After all, it’s one of the world’s largest wasps – nearly two inches long, and with an armored orange and black body that looks like a piece of heavy construction equipment. I admired the photos and showed them to my son, who has an enthusiasm for buzzing insects (and, for that matter, heavy equipment). What made the situation surprising was not the content of the photographs, but the location where they’d been taken. The friend who sent them hadn’t been traveling in Asia, he’d been just down the road in Blaine, Washington, a coastal town on the Canadian border, less than 40 miles from the island where I live.

Finding a species thousands of miles outside of its home range is nothing new. Insects, plants, and other stowaways arrive on our shores all the time, tucked accidentally into ballast, shipping containers, airline freight, or even luggage. Most remain obscure, yet in the weeks since receiving that email, the Asian giant hornet has made headline news across the country. (And the friend who sent me those photos has grown weary of giving interviews.) Yes, they are scary-looking and pack a fierce sting, but the real danger comes from their habit of feasting on honeybees. Given the many other threats facing our most prolific domestic pollinators, the arrival of a predator known for casually ripping their heads off sent shivers through the agricultural community. While most entomologists are sheltering at home during the pandemic, those trying to chase down and eliminate the Asian giant hornet have been deemed essential workers.

Photo via Washington State Department of Agriculture

Nicknamed “murder hornets” in the press, giant hornets are known in Japan by the far milder title, “big sparrow bees.” Long familiarity has apparently lessened people’s fear, and locals in rural areas are known to track the hornets to their underground nests and dig up their larvae as a tasty traditional snack. In fact, it is the demands of those larvae that make the adult hornets so formidable. Growing insects require protein, so when giant hornets attack honeybees they are gathering food for their offspring, not for themselves. (The adults fuel their own activities by lapping up tree sap.) It’s telling that hornets raid beehives mostly in late summer and fall, when their own nests have reached maximum size, filled with thousands of larvae demanding a massive influx of food. Yet seeking those calories from such well-defended sources is an unusual habit, and it explains a great deal about how giant hornets evolved.

Any animal that wants to exploit the concentrated food in beehives requires special strategies. Honey badgers in Africa have developed exceptionally tough, sting-resistant skin, for example, and giant hornets are also very well armored. But the hornets’ main evolutionary adaptation boils down to size – massive bodies to overpower their prey, and overdeveloped mandibles to tear them apart. Without such unusual hunting habits, it’s doubtful that giant hornets would ever have become large enough to earn their name. In Japan, local honeybees have learned to retaliate by swarming their attackers in a tight ball, killing them through heat and suffocation. But western honeybees have no such defense against the hornets, which is why beekeepers and farmers here are so worried. For anyone concerned about wild pollinators, however, there is another question worth considering. What else do giant hornets eat?

Photo via Washington State Department of Agriculture.

Early in the season, when their nests contain only a few larvae to feed, giant hornets target insects individually, particularly large-bodied mantises, moths, and butterflies. But when they need a bigger payoff, the same skills that give them access to beehives put other highly social species at risk. That list includes things like paper wasps and yellowjackets, which may come as welcome news to some readers. But there is also the possibility that bumblebees could be on the menu. Most entomologists think that chance is low – bumblebee nests are relatively small and well hidden, and hornets don’t generally target them in Asia. But invading species often develop new habits in new environments, so the impact of giant hornets on native insects will be hard to predict.

My son and I recently discovered a nest of black-tailed bumblebees in our orchard. They’ve set up shop in an old vole tunnel, and we’ve talked about erecting a tiny fence to protect the entrance from our chickens and ducks. If giant hornets enter the picture, we may have to take extra measures. Beekeepers in Yunan, China are known to station guards by their hives to knock down attacking hornets with sticks or tennis rackets. I hope it doesn’t come to that in our neighborhood, but if it does my son and I will be there, swinging away. And snapping a few pictures to send to our friends.